Malawi: cash, politics and dodgy elections

Scandal over theft of public funds may have cost Joyce Banda her presidency

Chimwemwe Lusungu was one of the first beneficiaries of Malawi’s much- touted economic miracle, the result of a large-scale national programme that subsidises agricultural inputs, mainly fertilisers and seed.

Within five years, her maize yields doubled and her life changed: she had enough to feed her six children and surplus to sell. But now the 45-year-old widow from Bunda in Lilongwe has neither maize to feed her family nor cash to buy food or pay other vital expenses such as school fees.

“I was struck out from the list of beneficiaries because I was told that government didn’t buy enough fertiliser to distribute to everyone as per usual,” she said when asked why she could not get fertiliser last year.

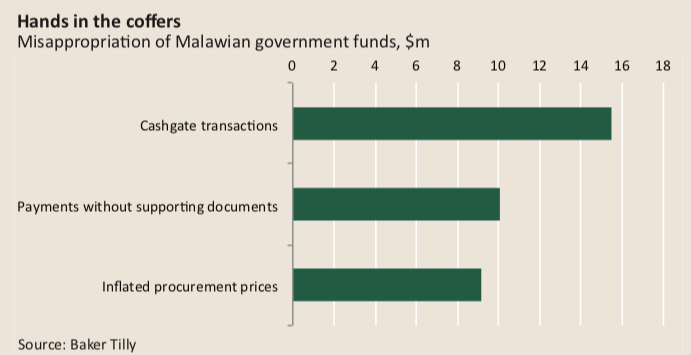

Mrs Lusungu blames her situation on “Cashgate”, a corruption scandal in which senior public officials, bankers and businessmen allegedly siphoned an estimated 6.1 billion kwacha ($15.5m) from government coffers, according to Baker Tilly, the British audit firm hired by Joyce Banda while still president to investigate the stealing of public funds. “I ended up voting against President Banda because Cashgate happened under her and money that could have been used to buy me fertiliser was stolen,” she said.

Mrs Lusungu is not the only one who voted against the incumbent in the May election because of the scandal. So did Edward Phiri, a primary school teacher who works near Lilongwe, the country’s capital. He claims that he went without pay for three months, from September to November 2013, because the Cashgate theft affected the country’s payment system. Worse, he blames the racket for indirectly killing his five-year-old daughter.

“I lost my child in hospital because the hospital had no drugs to treat malaria and it’s all because of corruption,” he said. “How can people steal such huge amounts of money from government?”

Mrs Banda, 64, initially enjoyed huge goodwill from the many who hated the autocratic style of her mercurial predecessor, Bingu wa Mutharika, who died in office in April 2012. She won the backing of foreign donors and the International Monetary Fund when she pushed through austerity measures, including a sharp devaluation of the kwacha, to stabilise the farming-dependent economy.

Her administration’s stellar beginning, however, was tarnished by Cashgate. The first hint of the scandal came when Paul Mphwiyo, the government’s budget director, was shot three times and left for dead by unknown assailants in September 2013. The story goes that Mr Mphwiyo, appointed by Mrs Banda to investigate the looting of the public purse, was attacked when his investigation got close to unveiling the truth.

In the wake of his attempted murder, police raids targeting several high-level officials uncovered wads of cash hidden in their cars and homes. Mrs Banda responded by sacking her cabinet. This was followed with the arrests of more than 80 people, who included bank tellers, senior and low-level civil servants and businessmen. The anti-corruption bureau, working with the police, confiscated wealth that could not be explained and sealed off mansions that belonged to humble government clerks.

They stand accused of exploiting a loophole in the government’s payment system—the Integrated Financial Management System (IFMIS). In addition to the Cashgate transactions, the British auditors found payments without supporting documents that accounted for an additional 4 billion kwacha and supply contracts which had been inflated by 3.6 billion kwacha. All told, the state was defrauded of about $32m, almost 1% of Malawi’s annual GDP, in the six months between April and September 2013.

Among the arrested was Ralph Kasambara, former minister of justice and constitutional affairs, who is now on trial for money laundering. Mr Kasambara is also facing charges related to the attempted murder of Mr Mphwiyo.

But this was not enough to change the hearts and minds of an angry nation heading into an election. Urban voters in particular criticised Mrs Banda’s response as ponderous and ineffectual. Foreign donors, who contribute almost 40% to Malawi’s annual budget, also lost trust in her administration. In November donors decided to withhold $150m for the 2013-2014 financial year. They stipulated that the aid would only be released when the Banda administration sealed the IFMIS loopholes and prosecuted those involved in the multi-million dollar heist.

Mrs Banda went into the May election crippled by a disheartened donor community and a disillusioned electorate to face 11 other presidential candidates. These polls turned into the most closely contested election since the end of one-party rule 20 years ago. Opposition parties went on the offensive, accusing Mrs Banda of allowing corruption to flourish, and promised to get to the bottom of Cashgate, a message that resonated with the electorate.

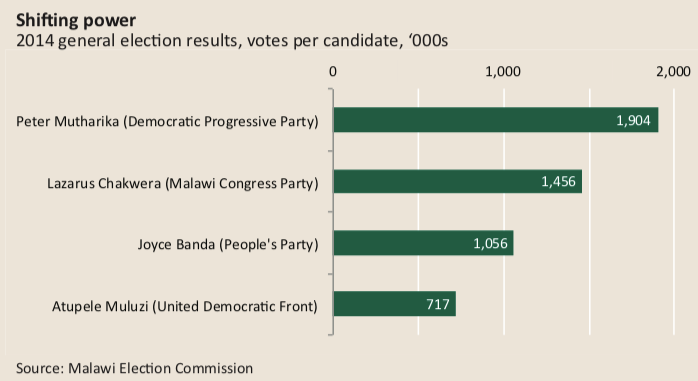

On May 24th, four days after voting closed, the Malawi Electoral Commission (MEC) released preliminary results based on a 30% vote count that showed Peter Mutharika, the younger brother of the late president, leading with 42%, followed by Mrs Banda with 20%.

On the same day, Mrs Banda and two powerful opposition parties, the United Democratic Front (UDF) and the Malawi Congress Party (MCP), demanded a recount, protesting that the vote was rigged.

The election was “fraudulent and with rampant irregularities”, she said, claiming that hackers had broken into the MEC computers and that in some constituencies ballot tallies exceeded the number of registered voters. In Machinga, a rural town in southern Malawi, 184,223 people voted when only 33,778 voters were registered, the protesting parties claimed. In Dowa West, a district in the central province, an MCP stronghold, 70,845 people registered but the final tally sheet showed only 1,164 voted.

“In the central province, we found out that more than 4,000 people voted when only 2,000 were registered,” said Gustav Kaliwo, the MCP’s secretary-general.

The electoral commission admitted that it had problems: voting materials turned up at polls several hours late and ballot papers were sent to the wrong voting stations. The MEC had to extend voting in some urban areas into a second day. Initial counting was held up by a lack of lighting and generators at polling stations.

Mrs Banda used these suspicious glitches and her evidence to demand new elections within 90 days. To guarantee a credible outcome in the new polls, she promised that she would no longer be a candidate. Her decision triggered protests in Limbe outside the commercial hub of Blantyre. Supporters of Mr Mutharika were upset that Mrs Banda had annulled the election and smashed shop windows. The MEC and Mr Mutharika challenged her demand in court, alleging that Mrs Banda lacked the consti- tutional power to annul the elections.

The high court ordered the elections body to do a manual vote recount within eight days as demanded by the electoral laws. The ruling, however, was a hollow victory for Mrs Banda. It was made on May 30th, exactly eight days after voting closed on May 22nd and thus a recount could not be done.

In the end Mr Mutharika won the election with 36%, followed by Lazarus Chakwera, the MCP candidate, with 27.8%. Mrs Banda was third with 20.2%.

In the months following the election, the debate about the election turns on two issues: was the election stolen from Mrs Banda? Or did Mrs Banda lose because of Cash- gate and the scandal surrounding the sale of the presidential jet last year?

“She lost the urban vote and the same is true in most rural areas where the elec- torate believes Banda stole their money meant for maize,” said Dr Henry Chingaipe, a political science lecturer at the University of Malawi. “But then again, the election was flawed,” he added.

Others think Mrs Banda lost the election because she challenged a very powerful syndicate. “Joyce Banda paid the price for doing two things; first for allowing such large scale of stealing to happen on her watch and secondly, for taking head on powerful people that were behind the looting of public funds,” argued Unandi Banda, a Malawian political commentator.

Mrs Banda lost because she appeared to be protecting close political allies from persecution in the Cashgate scandal, according to political analyst Lusekelo Mwafulirwa. “The Baker Tilly audit was meant to help restore confidence in her administration but that didn’t happen because the auditors refused to release the names” linked to the findings, he said.

Other allegations may have affected Mrs Banda’s chances of re-election, includ- ing the sale last year of a presidential jet to a controversial African arms group who then allowed her to use it for free, according to several press reports.

“The same is true with the sale of the presidential jet,” Mr Mwafulirwa added. “She had good intentions but when the deal was done her government failed to explain what happened to the proceeds, sparking speculation that she benefited from the deal.”

In her two years in office Mrs Banda managed to reverse fuel shortages, which were crippling the economy, and win back the donors who had suspended aid. But at the same time, she lost voters’ trust because of corruption.

“It’s a pity that I chose not to vote for her because of corruption in her adminis- tration; otherwise she was a much better president than the ones we had before,” Mrs Lusungu said, summing up what many still feel several months after removing her from power.

So far, no evidence linking Mrs Banda to Cashgate and other murky dealings has emerged. She has publicly denied any involvement. Mr Mutharika’s new administra- tion has vowed to win back international donors and to pursue the Cashgate criminals. No one knows whether this will mean going after the former president.

[author] [author_image timthumb=’on’][/author_image] [author_info]Mabvuto Banda is an award-winning investigative journalist based in Malawi. He has reported for Reuters for ten years and also contributes to New African magazine, New Internationalist as well as the Inter Press Service and other online publications. [/author_info] [/author]