South Africa’s municipalities

The ruling party’s mismanagement of cities may relegate it to the rural backwaters

The ruling African National Congress (ANC) risks relegation to rural party status for mismanaging many of South Africa’s major cities, opening the field for opposition parties to control the country’s economic strongholds.

After intense competition from the Democratic Alliance (DA), the liberal official opposition, and the new populist Economic Freedom Fighters (EFF) during May’s general election, the ANC won just over 62% of the vote, down from previous pinnacles of nearly 70% during the 1999 and 2004 elections.

In power for 20 years, the ANC has neglected local government, which is plagued by financial and administrative mismanagement. Municipal officers with poor accounting and management skills have been unable to collect property taxes or payment for services such as water and refuse removal in many of the cities controlled by the ruling party. Residents owed the city of Johannesburg $1.5 billion last year and overall, big cities failed to collect $4.7 billion, according to research by the South African Institute of Race Relations (SAIRR), a Johannesburg-based think-tank.

More than half of local government income comes from these service charges, said Georgina Alexander, one of the authors of the SAIRR report, during an e-mail exchange with Africa in Fact. “If the municipality is unable to collect the money it is owed, it will struggle to raise the money needed to carry on and expand current service delivery,” she added.

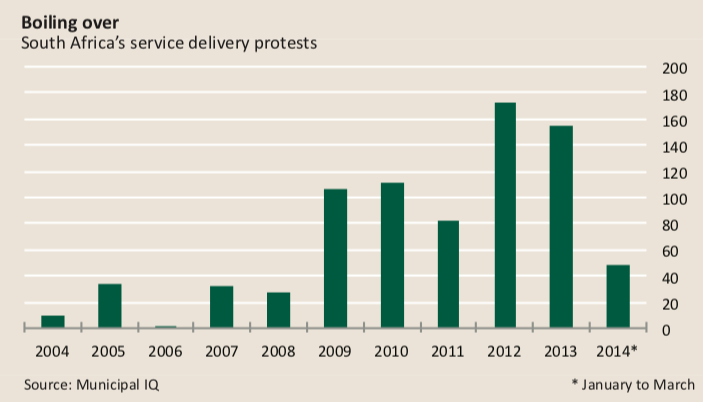

Partly as a result, service delivery is poor and residents are taking to the streets to complain, according to the South African Local Government Association, the organisation that represents municipalities. In the first three months of this year, 48 service delivery protests took place, compared to 155 in the whole of 2013 and 173 in 2012, according to Municipal IQ, an independent South African organisation that monitors urban issues.

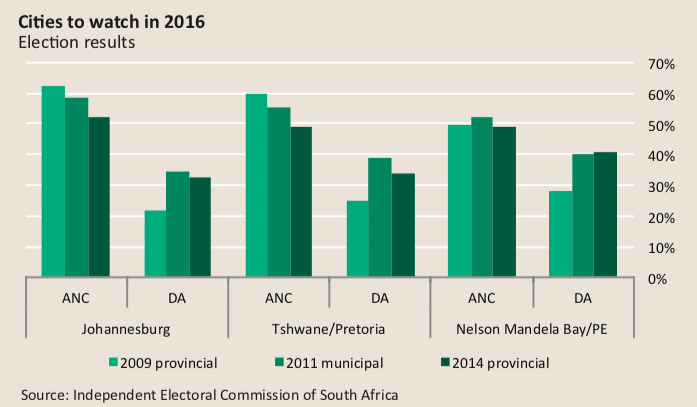

The ANC is bracing itself for the 2016 local government elections, which may further erode its grip on urban areas. Results from May’s election show that the ruling party has lost ground in seven of the country’s eight metropolitan municipalities, districts with more than 500,000 voters.

The ANC raised its proportion of the vote only in Durban/eThekwini in KwaZulu-Natal province, home of President Jacob Zuma and the province that provided about 20% of the party’s vote in the national election. The DA controls only one metropolitan district, the city of Cape Town. It retained its grip on South Africa’s legislative capital and second most economically important city with 59.3% of the vote.

“Poor voters are critical but still loyal” to the ANC, said Steven Friedman, director of the Centre for the Study of Democracy, a joint initiative of the University of Johannesburg and Rhodes University, both in South Africa. But “loyalty is diminishing within the black middle class. The ANC lost the black middle class in urban areas in the [May] election and the underlying problem is anger at corruption” and the lack of significant black ownership and participation in the economy, he added.

The DA won Cape Town in 2006 by highlighting the ANC’s weaknesses in governing municipalities, according to political analysts. In the 2011 municipal elections, the ANC won 52% of the vote in Port Elizabeth/Nelson Mandela Bay in Eastern Cape province, the ANC’s heartland and birthplace of party leaders Nelson Mandela, Thabo Mbeki and Oliver Tambo. This proportion slipped to 49% in May’s general election.

“The trend over the last three elections [in 2009, 2011 and 2014] shows metros are more contested and voters are willing to vote for the opposition, creating more heightened competition,” especially if the ANC does not improve its management of the municipalities, said Collette Schulz-Herzenberg, a Stellenbosch University research associate, during an interview with Africa in Fact.

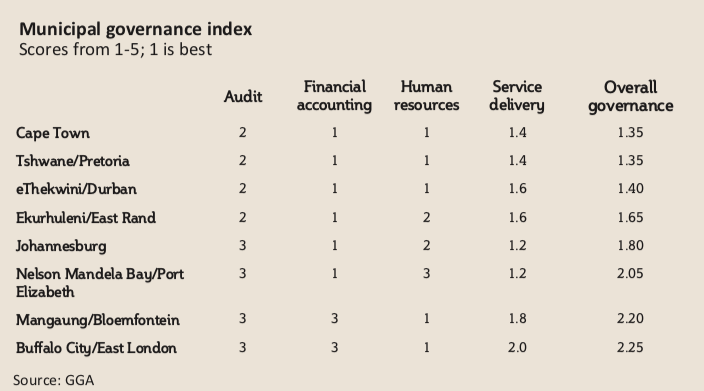

Which cities and urban precincts are likely to fall to the opposition in the 2016 local elections? An answer may lie in looking at local government performance as meas- ured by the South African Municipal Governance Index, compiled by Good Governance Africa (GGA) in April 2014. GGA examined audits and reports on financial accounting, human resources and service delivery and then rated each of these four criteria from one to five, where one is best. The aggregate score is the average of these four ratings. The lower the score the better run the city.

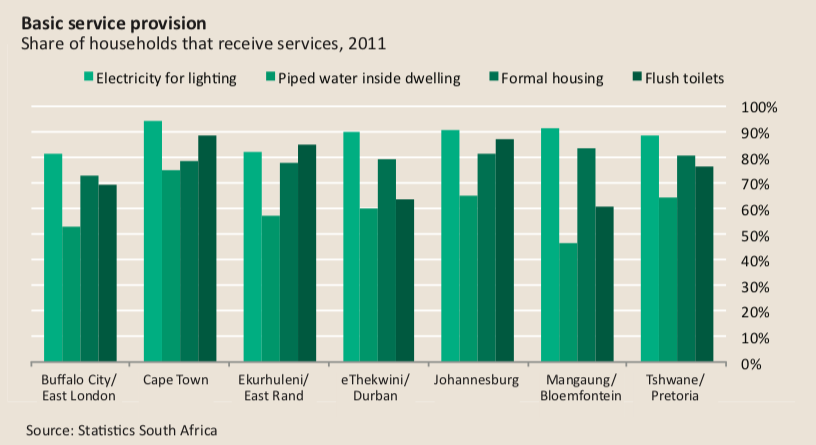

For the most part, urban municipalities delivered better services than small towns and rural areas. DA-led Cape Town and the ANC-led Pretoria/Tshwane top the list. Each achieved an overall score of 1.35. However, three other metros were not far behind: eThekwini/Durban, Ekurhuleni/East Rand and Johannesburg.

The worst-performing metros were Mangaung/Bloemfontein in the central Free State province and Nelson Mandela Bay/Port Elizabeth and Buffalo City/East London, both in the southern Eastern Cape province. Residents in these two municipalities suffer the effects of persistent under-spending and poor service delivery, particularly refuse removal, the provision of piped water and flush toilets.

Last June the mayor of Buffalo City/East London, her deputy and the council speaker were arrested on charges of fraud, corruption and money laundering, according to Paul Ramoloko, a police spokesman.

Most municipalities failed to deliver basic services and maintain fiscal discipline because the city managers and financial officers lack the appropriate accounting and financial training, according to Terence Nombembe, who retired as auditor-general in November 2013. Before he retired, his office released a report on municipal audits for the 2011-2012 period.

This report stressed the lack of discipline in financial management and insufficient in-year reporting and monitoring by municipal bosses. This resulted in poorly prepared financial statements, which often required corrections. Only 48% of all 278 municipalities received clean audit opinions, according to the 2013 report.

The inability of local authorities to spend money and deliver services is frustrating residents and inciting street demonstrations, said Zwelethu Jolobe, a University of Cape Town politics lecturer who has researched service delivery protests.

“Decision-making at the local government level is unresponsive and un- democratic, thereby undermining people’s livelihoods and interests,” he said last June. “Protesters are frustrated against perceived corruption, sudden enrichment and conspicuous consumption by municipal councillors and staff,” Mr Jolobe added.

If the ANC does not take up the gauntlet and deliver goods and services, re- move bad performers from municipalities and appoint qualified people, residents will do more than protest. They may turn to the ballot box and promote the opposition to manage the country’s major urban areas, according to political analysts.

As Mr Friedman warned: “The big story of [May’s] election from the ANC’s perspective is that there is a real prospect that the ANC is in danger of becoming a primarily rural party.”