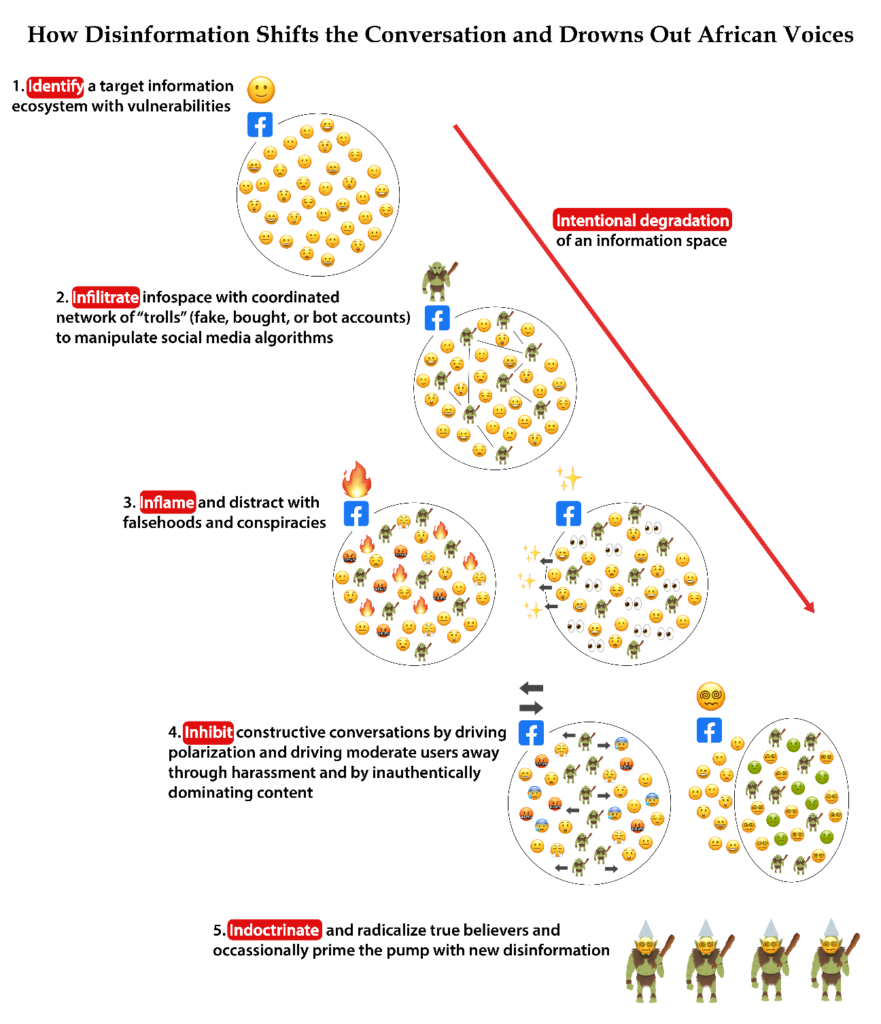

Africa’s circuits of information are overloading under a surge of disinformation. The growing problem is undermining the open dialogue and fact-based reality required to sustain democratic processes – and the outcomes are increasingly spilling into real-world instability.

From the Anglophone crisis in Cameroon, where pro-government actors and pro-Ambazonia separatists spread malicious falsehoods and urge followers to “kumkumize (kill) instantly”, to recent elections in Kenya and Nigeria that were hotbeds of algorithmic tactics to skew the truth and underhandedly seize the narrative, to the Sahel states where insecurity is deepening while conspiracies and cynicism are mainlined into public discourse through deceptive and deliberate manipulations, political actors with self-serving – and often plainly anti-democratic – agendas are turning information into a weapon in Africa.

A wake-up call for how quickly disinformation can escalate and incite deadly violence came from the Democratic Republic of Congo when disinformation “pressure groups” ratcheted up rhetoric and conspiracies that resulted in the deaths of five peacekeepers and more than 30 protesters in the summer of 2022.

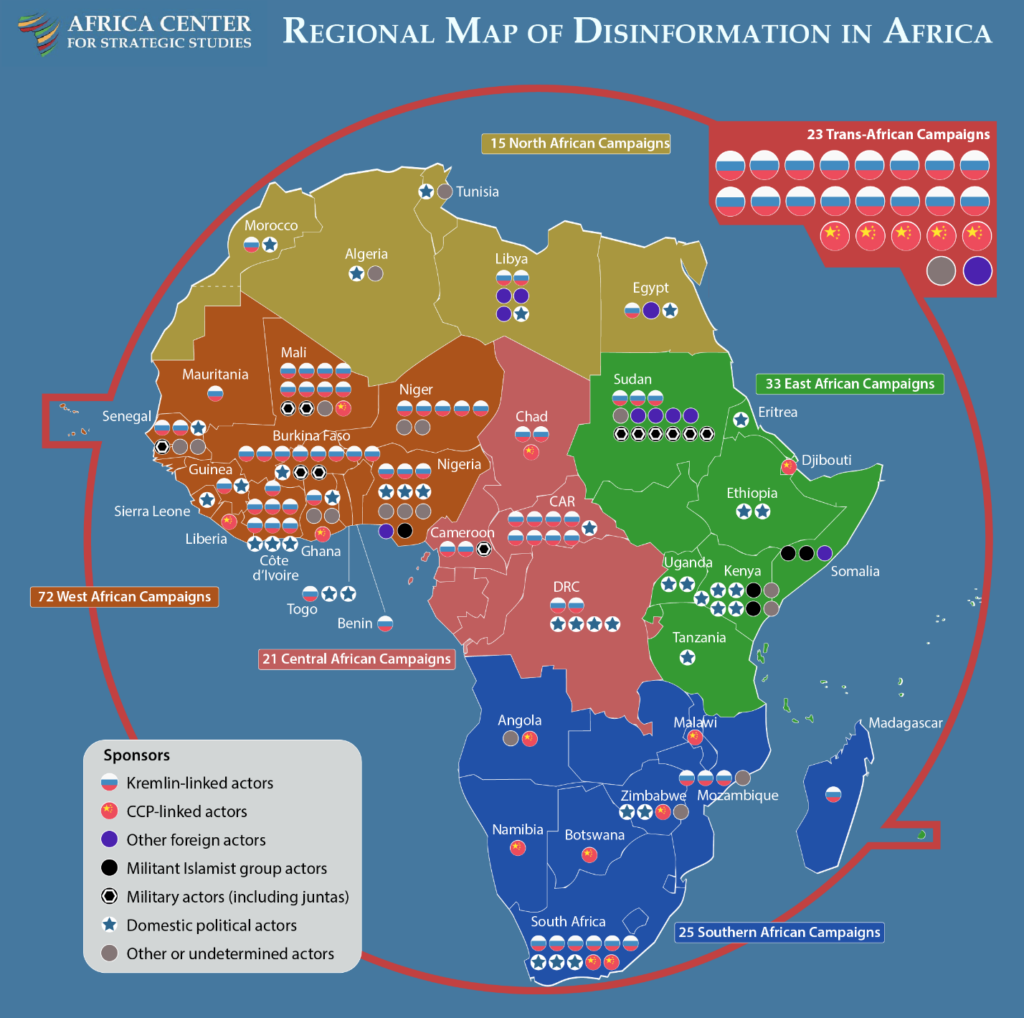

As of 2024, researchers have documented more than 189 disinformation campaigns targeting the African continent, a nearly fourfold escalation since 2022. These attacks interfere with the networks that connect the 400 million+ Africans now using social media regularly (up from just 100 million in 2016). Many of these users rely on platforms like Facebook and X as their primary source of news.

The head-spinning uptake of smartphones and social media platforms in Africa points to the appealing power these tools have to revolutionise information’s accessibility and decentralisation. These technologies, however, have fundamentally recircuited the continent’s networks and flows of information, bringing a trail of vulnerabilities and, because surge protectors are not yet in place, overriding what existed of fact-based constraints to de-escalate rhetoric to ensure reliable news options and to enable conducive spaces for communication. Unlike analogue propaganda, social media platforms allow disinformation sponsors to easily cloak their identity while supercharging their reach to instantly mislead millions of users.

The result is what media sources in Burkina Faso have decried as a crisis of “anti-communication”, what concerned Kenyans have described as a society wracked by “information disorder”, and what other African media monitoring groups are calling an “infodemic”.

This does not have to be the story of digitalisation in Africa. Like much of the world, a reckoning with these emerging tools and a creative restoration of credible hubs of information is sorely needed to re-anchor national politics and psyches to reality and away from extremist silos.

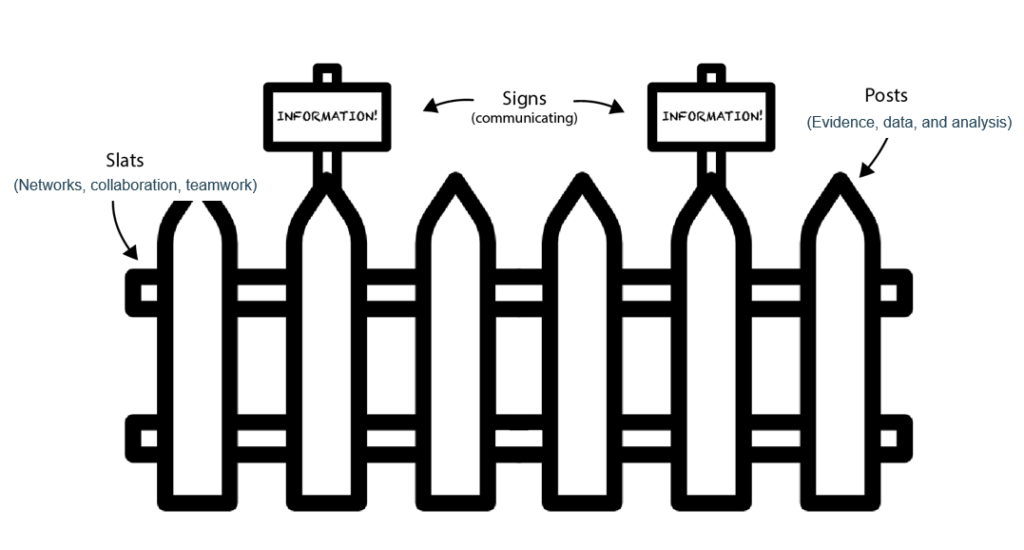

The immediate challenge is to create surge protectors – what we can simply call “fences” – to keep disinformation out and empower online users to protect themselves from manipulative interference. African researchers and practitioners, including more than 30 organisations that have contributed to documenting the extent of disinformation in Africa, are putting their heads together with concerned citizens and partners to put this type of resiliency in place.

This counterstrategy works best when led from the ground up, with citizens recognising the threat and seeking to reclaim sovereignty over their info spaces. This approach has shown results in the Baltics, Taiwan, and Sudan (prior to civil war) when spearheaded by local non-governmental actors (NGAs). In these cases, a variety of NGAs combined forces to draw on their skills and specialties to respond quickly and adaptably to disinformation attacks in ways that resonated and cultivated trust with their fellow citizens. In Sudan, groups like Beam Reports published Arabic reports on disinformation and took their findings to Facebook pages where they used humour and local dialects to puncture the appeal of foreign-backed disinformation. While each success story involves strategies tailored to individual contexts and practices, the approaches embraced by effective counterstrategies all involve a three-part process that we call the fence framework. Fences have three parts (posts, slats, and signs):

Posts

Combating disinformation starts with data – good, rigorous information about how online and adjacent offline spaces are manipulated and polluted with fictions. Data scraping and digital forensics help gather and interpret insights and focus counterstrategies, providing sturdy foundations for fenceposts. Researchers have an expanding arsenal of tools and methods at their disposal for developing this knowledge base, including the ABCDE approach (uncovering disinformation actors, their behaviours, content they spread, the degree of its reach, and the effect it has), the concept of tracking identifiable malign TTPs (tactics, techniques, and procedures) through a taxonomy elaborated through the DISARM framework, and the OpenCTI platform to organise data, explore connections, and share findings.

These tools enable more effective analysis of the content disseminated on social media, as well as a better understanding of the demographics and coordination of disinformation campaigns and the specific TTPs used in each campaign. For example, in some Sahelian countries, researchers have identified that brute force copy-paste techniques are a simple but effective means commonly used in Russian-linked disinformation campaigns.

Academic researchers, investigative journalists, factcheckers, and analysts from media, youth, tech, and civic NGAs are all part of generating these insights. We are starting to see trainings scaled up and toolkits become more accessible to African users, allowing this knowledge to be generated on the continent. Groups like Code for Africa, Debunk.org, and DFRLab all offer online courses for African analysts interested in fighting disinformation.

Locally generated insights are made sturdier when they go beyond digital data and involve ground truthing to better interrogate why certain TTPs are finding soft spots in a specific region or demographic. Historical inquiries and local interviews in African languages are indispensable to making sense of digital data. Here, researchers in Africa have excelled, offering a rich set of publications that reflect on why disinformation sticks in certain places and what ways it may be dislodged.

This grounded understanding of disinformation underscores the importance of basing research on the continent and expanding access to training and data for African researchers. This is an uphill struggle as social media companies continue to limit transparency and deprioritise African requests for assistance.

Slats

Fighting disinformation effectively is a team sport. Slats are the connective and structuring elements of counter-disinformation. In practice, this means establishing standards, shared lexicons, trusted networks and collaborations to exchange information and collectively tackle the huge task of monitoring and addressing disinformation across boundless online spaces.

Research on disinformation campaigns must be exchangeable and interpretable by practitioners to have an impact. Recently, there have been breakthroughs in establishing this type of interoperability with experts converging around a package of terms, methodologies, and taxonomies that establish (F)IMI [(Foreign) Information Manipulation and Interference] analysis standards. This set of shared definitions and approaches allows a democracy NGO in Accra to talk to a media monitoring analyst in Nairobi about the threats they are seeing in their information spaces and piece together the bigger picture. Because disinformation is borderless, this type of collaboration is essential for tracking sprawling campaigns and warning neighbours about emerging TTPs.

Setting up and sustaining trusted networks requires resources. African practitioners are creating these spaces but need support to fund workshops and conferences where NGOs can share strategies, learn about emerging technologies, and best practices, and form relationships that can lead to data-exchanges and collaborations. Often the problem of disinformation has been seen by partners as so immense and complicated that it has brought cautious approaches, that while thoughtful and measured, have verged on paralysis. Thankfully, more initiatives are coming online but will need to be coordinated to avoid redundancies and outdated trainings in this fast-moving space.

The vision for interoperable and open-source collaborations comes from cyber security, which has more than 30 years of lessons to offer counter-disinformation. Tools like OpenCTI and the Styx data model that underlie it are adapted directly from cyber defence systems. The gold standard of slats for cyber are ISACs (Information Sharing and Analysis Centers). Therefore, the goal is for African counter-disinformation organisations to set up a series of loosely affiliated ISACs – these can take a variety of forms and involve different levels of formality – that create a decentralised ecosystem of citizens defending their information spaces together. Through these efforts, hubs of credible information can start to form a latticework of stability in our new information landscapes.

Signs

Fence signs inform and warn the public about the dangers of disinformation. This is the critical third step of leveraging data and networks and turning them into action that can mitigate disinformation. This includes strategic communication during moments of crisis or confusion, programmes to alert and arm the public over the long and short term, commitments from politicians to disavow disinformation, tailored regulations from policymakers, and pressure on social media companies.

Different disinformation campaigns need different responses. The degree and effect of a campaign informs what inoculation and communication strategies to draw on to remove or contain the threat. Tools like the kill chain model and the DISARM responder TTPs can help guide practitioners in effective responses, ranging from long-term digital literacy programmes, to anticipatory pre-bunking campaigns, to lobbying platforms to take down abusive content. There is rarely a silver bullet, and the work of defusing disinformation is endless. Often, fast-paced responses require a different skillset from research and a different set of practitioners skilled in the arts of breaking through the noise and reaching people in their information bubbles.

In South Africa, Media Monitoring Africa, with its dashboards and outreach, provides an adept example of empowering the public to understand disinformation and navigate their digital spaces, especially during moments of information volatility, like elections.

Effective countering of disinformation also involves increasing the strategic approach of many fact-checking platforms that are already active and doing important work in Africa (like the country-level teams that are part of coalitions like the African Fact-Checking Alliance (AFCA), the International Fact-Checking Network (IFCN), and the Africa Facts Network). These platforms should coordinate to avoid redundancy and enable users to make requests to verify facts before any significant engagement on social networks. Systems should also be put in place to flag recurring sources of disinformation and to highlight, remove, or label them for users. AI tools – like chatbots and advanced dashboards – should increasingly be tapped to reach and inform individual users who are inundated with disinformation attacks that are already using AI to expand their reach.

As long-term strategies are developed, training to spot disinformation and to learn digital literacy skills should be expanded and incorporated into classroom curriculums. These efforts can increase their impact by prioritising young people who have a strong presence on social networks and disadvantaged populations who often do not have access to up-to-date or accurate information – or may be tempted to become part of the growing disinformation-for-hire industry in Africa.

The last mile of communication to vulnerable users is too often an afterthought, even when disinformation is detected. Given the fragmented nature of information networks today, effective education and messaging increasingly must come directly from the sources people still trust, which, research shows, is often friends and family members. Finding ways to inform and equip these “micro-influencers” with key messages and factual talking points about disinformation and how to avoid it must therefore be part of the communications strategy. There is still much to learn about useful signposting, and more African examples and case studies of successes and lessons are needed.

African countries are staring down converging challenges of climate change, conflict, displacement, military coups, and economic crisis that are all worsened by disinformation, which is fuelling a sense of resignation and despondency. Escaping the trap of despair and disengagement with politics will require fostering different digital forums, where a future can be imagined and political pathways towards it can be constructed on firm and factual grounds.

Currently, counter-disinformation fences are sporadic and full of gaps in Africa (as they are in much of the rest of the world). But in the future, if sustained resources are focused on building these defences, there may come a point when we can start to conceptualise them less about what they keep out and more about their connective potential as hubs for information exchanges and engagement. In this scenario, we may start to think of disinformation resiliency efforts as creating public gathering places – as stages (with posts, platforms, and productions) in our digital forums where a future, and a way out of the nihilism of disinformation, can start to take shape.