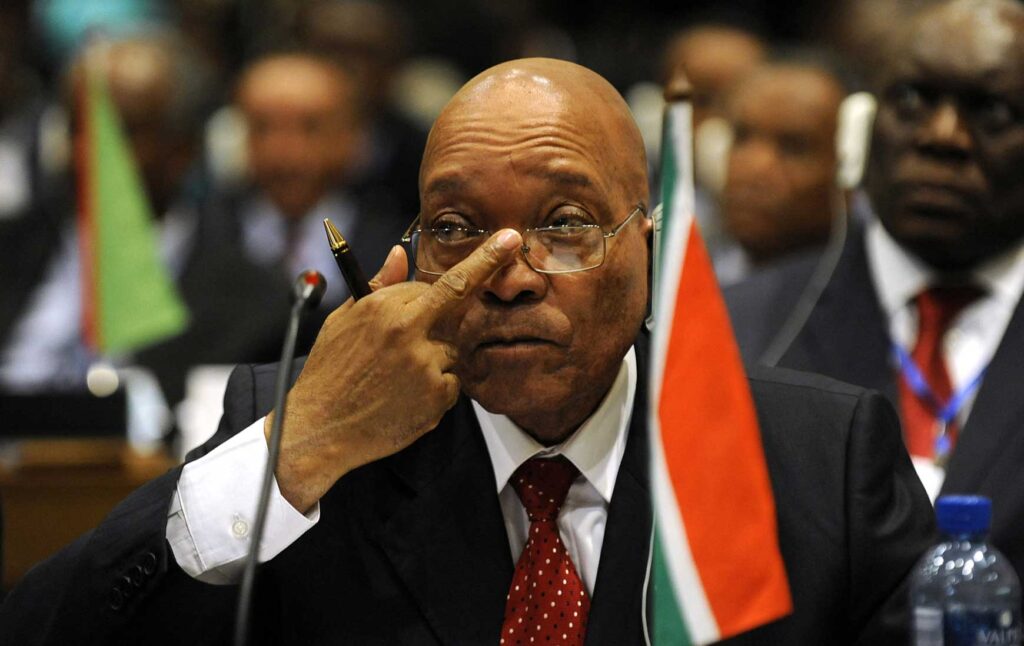

Jacob Zuma’s toxic legacy

President Jacob Zuma’s presidential style has undermined the South African constitution, the rule of law and rational policymaking. It has undermined the democratic idea of separation of powers between different spheres of government – the executive, legislature and judiciary. All this is because Zuma’s personal, family and factional interests have overridden the public interest.

Unless checked, his presidential style will almost certainly accelerate South Africa’s slide towards a failed state, a society more polarised along racial lines and the breakdown of the ANC itself.

How did this happen? How can it be that a country whose transition from minority-rule authoritarianism to democracy was celebrated all around the world, and whose founding constitution is regarded as one of the most enlightened ever penned, has declined to the status of a moral pariah all around Africa? To answer this question, we need to look critically at Zuma’s presidency, and what he has done with it.

“Right now, to make a decision you need a resolution, decision, collective, petition. Yoh! It’s a lot of work,” Zuma said last year, visiting a primary school in Tembisa, east of Johannesburg. He went on to joke that if he were a dictator of South Africa for six months, he would solve all the country’s problems. His remark was meant as a joke, Zuma-style, but it says much about the man’s views of governance, policy and decision-making. A number of key influences have shaped Zuma’s presidential style. The first is that he has adopted a traditional style of governance.

One ANC youth leader has described Zuma’s presidential style as that of a traditional African “chief”, in that he has used the office of the presidency to distribute state patronage to allies, friends and family. On this view, the president, as head of state, is everybody’s chief, including the country’s several kings.

An old-fashioned customary view would have it that public property is communal property, which is controlled by the chief in the interests of the community. However, in practical terms, this has often turned out to mean that a chief controls public property essentially at his own behest. Indeed, in South Africa today some traditional leaders and chiefs use communal land – which, on a customary view, they should govern in consultation with the community – as their private property, claiming that this is sanctioned by “culture”.

Similarly, Zuma appears to believe that as uber-chief, all state property, funds and jobs are his to control in his own private interest. For instance, the chief is entitled to live in bling – to show his or her status. That is one reason he still maintains that he did nothing wrong in spending R246 million of public money on his private home in Nkandla, even though a finding by the public ombud found that he had breached the constitution in his attempts to avoid being held accountable.

On the old-fashioned customary view, the chief is also never publicly challenged. In his quarrels with Julius Malema, the former leader of the ANC Youth League, the issue that most outraged Zuma was the fact that Malema refused to stick to the dictum, that “once a king (Zuma) has spoken, no one can speak”.

Furthermore, the chief isn’t accountable to “his” people. It’s the other way around: the people are dependent on the largesse of the chief; the chief is the law. In the same way, Zuma has rarely allowed himself to be held accountable by the ANC, by parliament or by democratic institutions or by ordinary voters. His view is apparently that the courts, parliament and judiciary must bend to the will of the chief.

Secondly, Zuma’s formative work experience in the ANC’s intelligence and underground structures has clearly shaped his approach to presidential management. Zuma’s most important two posts in exile were as chief of ANC intelligence and head of underground structures. And he manages his presidency as if he were the chief of a liberation movement’s intelligence operation or underground structures.

In the ANC intelligence and underground structures in exile, consultation occurred only among the top leadership, ostensibly for security reasons; lower-level members were simply expected to listen and obey. The ANC’s intelligence wing was certainly the most shadowy, secretive and heavy-handed organ of the party in exile. Under Zuma, a similar culture of operation appears to have infused the South African state and the ANC. Journalist Ranjeni Munusamy has described Zuma’s securitisation of government as an “undercover state”.

Zuma controls all the intelligence, police and security services through his appointments of pliant candidates to top positions. Some worked under him in the ANC intelligence and underground structures, while others worked in the apartheid services. In quite a number of cases, he has appointed people who lacked any relevant qualifications for the role.

Instead, his appointments emphasise one quality: their personal allegiance to him. Zuma political appointees are personally indebted for their jobs to him, and therefore serve him personally, rather than the interests of the public. They are expected to compromise themselves in his defence or to bend the rules in his favour, so linking their personal futures with that of the president.

Baldwin Ngubane, the recently-resigned chairman of Eskom, is a case in point. A close ally of Zuma, the president recycles him from one state entity to another. He was chairperson of the embattled South African Broadcasting Corporation (SABC) before moving to Eskom, and both organisations were mired in scandal under his watch.

This approach also means that the same people are appointed to key positions in a game of rotation, because the president trusts them. Brian Molefe, another confidante of the president, was recently reappointed as CEO of Eskom. He had resigned a few months after being implicated in dodgy relations with Zuma’s business associates, the Gupta family, in former Public Protector Thuli Madonsela’s state capture report.

Under the Zuma presidency, the intelligence, police and security services have been used to fight internal ANC party battles. Zuma is said to have fired former finance minister Pravin Gordhan on the basis of an “intelligence report” that alleged that Gordhan was plotting with foreign governments, companies and business leaders – so-called “white monopoly capital” – to unseat Zuma.

State Security Minister David Mahlobo afterwards denied that the intelligence services were responsible for the report. Yet the fact that Zuma saw fit to produce a report, of whatever provenance, suggests that he continues to operate in the cloak-and-dagger manner of an intelligence chief.

Thirdly, Zuma has made populism a dominant strand of the ANC. Populism in the political dimension is an “anti-status quo discourse that simplifies the political space by symbolically dividing society between “the people” (as the underdogs) and “its Other”, according to the Latin American scholar Francisco Panizza. The “Other” that is supposedly in “opposition” to the “people” can be symbolised as a “dominant” political or economic class or an ethnic group or political party that is “deemed to oppress the people and deny their rights”.

On this view, populism is “indelibly associated with the theatre of the crowds” and “personalist” leadership. As part of this, it makes use of simplistic economic analysis, and urges the use of the state for redistribution, which often includes nationalisation programmes. Populist movements often claim to want to “restore” or establish “public order” and “traditions”, the latter often projected in distorted or conservative forms.

Zuma has tried to deflect criticism of his failure in government, and of his alleged corruption and personal misbehaviour, by claiming that “white monopoly capital”, “clever blacks”, and “third forces” are opposed to his attempts at “radical economic transformation”, supposedly meaning transferring wealth from whites to blacks. Zuma’s former ally Blade Nzimande, the general secretary of the South African Communist Party, has said that Zuma’s narrative of “white monopoly capital” and “radical economic transformation” had become rhetoric that allows the Zuma group to enrich themselves.

Zuma’s frequent calls for “traditional” resolutions of “African” disputes is classic populism. Populist leaders often say one thing in public, but practise the opposite behind closed doors. So it is that anyone who criticises Zuma’s hypocrisy is either a black person wanting to be white, or a white imperialist – another classic populist response to critical analysis.

Commentators often say that Zuma is seeking to abolish democratic institutions, including parliament, the judiciary and civil society, but he has mostly used them to entrench his loyalists in power. He has used them as an extension of his patronage networks, benefiting allies and their families.

In South Africa, patterns of corruption are increasingly sophisticated, with legitimate institutions, laws, policies and rules used as covers for self-enrichment. Corruption is increasingly carried out through what appear to be “normal”, “standard” and “credible” processes.

Such corruption is particularly prevalent in countries in transition, whether from colonialism or authoritarianism, or in South Africa’s case, from apartheid. In such countries the rules of the game are changing, contested, new, unclear or not yet settled, and the rule of law is not universally embraced.

Countries in transition often implement economic policies, described as “reforms”, which produce market distortions. These include laws focused on redistribution that favours a particular group, such as black economic empowerment. As part of all this, state-owned companies are often privatised cheaply, and sold to well-connected politicians and business leaders.

In many cases, the state procures products and services from companies under rules that compel redress of one form or another. Moreover, the rules are then manipulated to ensure that select business people or politicians and companies said to represent previously disadvantaged communities, gain state contracts.

In other cases, the state provides companies or business people with funding, creates favourable business conditions for them, or protects their trading or mining licences. For example, the state might exempt certain businesspeople from universal public rules, such as environmental regulations. Democratic institutions and state-owned enterprises (SOEs) are run in such a way as to appear to abide by “normal” rules, while laws, policies and social rules are manipulated for the convenience of the well-connected. The senior management structures of public offices, key democratic institutions and SOEs are packed with carefully chosen individuals who are in on the deceit, or prepared to look the other way, or simply too incompetent to identify corruption or other forms of misgovernance. The ANC’s policy of “cadre deployment”, according to which loyalists are appointed to key posts regardless of their actual suitability for the role, is a clear example of this.

With such people in place, the rules covering further appointments are skilfully manipulated. Nominations are called for, vacancies advertised for public positions, interview panels put together. Applicants who are not in on the deceit never make the short list. Quality candidates will learn that their CVs did not arrive on time, or given some other seemingly “legitimate” reason for their failure to make the short list.

Zuma has not achieved all of this on his own. The ANC under former President Thabo Mbeki was close to becoming a state in which the party’s leaders, members and supporters saw the state as belonging to the party. This phenomenon has only been deepened under the Zuma presidency. Zuma’s contribution has been to turn it all into a ‘partyarchy’ – that is, a party dominated by entrenched regional, ethnic, generational-or even class-based groups and their networks.

Zuma allows the different factions, networks and regions of the ANC to run their fiefdoms almost independently as long as they remain loyal to him personally. For example, the so-called “Premier League” of provincial premiers Ace Magashule (Free State), David Mabuza (Mpumalanga) and Supra Mahumapelo (North West) – are deeply loyal to Zuma. In return, they are allowed to run their own provinces as little fiefdoms, giving out tenders to loyalists, using public resources to marginalise critics and manipulating policies to enrich themselves.

Within the ANC, Zuma’s presidential style is based on trying to please the competing factions, networks and regions within the ruling ANC-Cosatu-SACP tripartite alliance. Above all, he takes no firm decision that might alienate any influential group, and tells each group what they want to hear.

Zuma only takes a firm decision when he needs to defend his personal interests. These include trying to escape current or future prosecution on charges of corruption, defending his family business interests or dealing with the aftermath of further revelations of his personal indiscretions.

As regards day-to-day governance of the country and his party, the president’s catch-all style means that he rarely makes a difficult policy decision. Instead, he will make a pronouncement in the broadest terms. This approach includes even situations that require decisive policy interventions, such as questions of foreign policy, economic growth and dealing with corruption.

The different factions of the ANC-led tripartite alliance have often supported him because they thought they had his support, given that he had appeared to agree with them in meetings. This is why they often announce their own policy stances as official after meeting Zuma, even though other factions might have diametrically opposed policy positions. Not surprisingly, this results in total confusion over what the real government policies are.

No one in government, in the ANC or in any external organisation knows what the government’s real policies are. This has led to paralysis at the heart of the South African government. The president’s misleading rhetoric, and the resulting double-talk in the political space, mean that those who devise or implement policies do not have adequate information available, or the wrong information, to do so effectively.

The same goes for potential new investors. If they do not know the government’s policies, and cannot find out what they are, they might simply withhold their investments.

Even government planners are confused, because the information they get from politicians makes it very difficult for them to allocate resources efficiently. Government officials are often forced to second-guess the government’s policies, which causes implementation paralysis. Senior civil servants will be reluctant to implement policies they are not sure are backed by the president or influential politicians in the ANC. It could be career-ending.

Since there is no certainty about policies, those with enough money can pay to have policies that favour their interests and see them implemented. Meanwhile, government leaders make outrageous promises, even if they know that the resources, capacity or detailed plans to make them possible are not available. Their promises create expectations among ordinary citizens, even though there is little chance that they will be acted on.

Confronted with burning issues, such as the 2016 “fees must fall” student protests, Zuma often opts for delay. Such situations would demand immediate decision, but a particular solution might alienate one of the alliance factions.

Instead, Zuma sets up task teams, appoints committees and establishes commissions, often composed of members from all the alliance factions. These teams take so long that the initial problem may have been forgotten by the time they announce their conclusions. Often they come up with vague solutions because they must please every faction. And they often consist of the “usual suspects” – the same individuals who had failed to deal with the issue in the first place.

In some cases they include individuals from the president’s inner circle who are part of the entrenched status quo, paradigm and mindset, and therefore unlikely to suggest fresh ideas or viable solutions. Aside from that, they do not inspire the kind of public confidence that might have gone to credible individuals from outside the president’s inner circle of influence. This approach allows the president to look as if he is acting decisively, without actually coming to a decision.

Zuma’s questionable personal behaviour, decisions and dealings have deeply divided the ANC. They have also split the governing ANC-SACP-Cosatu tripartite alliance and unleashed protests from civil society and opposition parties. His destructive presidential governing style has led to the break-up of Cosatu, the formation of the opposition Economic Freedom Fighters (EFF), and may push the SACP to stand as an independent party in the 2019 national elections.

To escape prosecution for more than 783 charges of corruption, Zuma desperately needs to ensure that his ex-wife Nkosazana Dlamini-Zuma succeeds him. If she becomes president, she will likely protect him from prosecution, and help to secure the wealth that Zuma, his family and allies have obtained through their involvement in state capture.

Even if Zuma secures the election of his ex-wife as his successor, the ANC may lose the 2019 elections, because the perception will be that she is his proxy. In that case, the opposition parties that win that election might well prosecute him.

If Dlamini-Zuma wins, ANC opponents of the Zuma/Dlamini-Zuma axis could breakaway and form a new party. If Cyril Ramaphosa – the ANC and South African deputy president, and strong contender – wins, the Zuma/Dlamini-Zuma faction could break away. Aside from the damage he has done to the country, Zuma might also bring about another break-up of Africa’s oldest liberation movement.

Such has been the legacy of the Zuma presidency.

An extract from the State Capacity Research Project report, BETRAYAL OF THE PROMISE: HOW SOUTH AFRICA IS BEING STOLEN, by South African academics

This article first appeared in Africa in Fact, Issue #42, July – September 2017