Egypt’s fine balance

A new investment law may boost foreign investment while also encouraging corruption

At the Trade Syndicate building in downtown Cairo, dozens of workers met with lawyers last May to plan their challenge to a new investment law that restricts contract oversight. Many were angry about questionable business deals between the state and investors, which had left thousands of ordinary workers without jobs.

These employees, who represented 15 companies that had been privatised under Hosni Mubarak, the deposed Egyptian president, gathered during a conference organised by the Egyptian Center for Economic and Social Rights (ECESR), a small local NGO. Some of the workers had challenged in court the state’s decision to privatise their companies, saying that these deals were corrupt, had grossly underpriced the values of the companies, and had profited the state and investors while seriously harming the interests of Egyptian workers.

Against all odds, the former employees of the privatised companies won some of these cases after the 2011 revolution and the companies returned to state control. Some even got their jobs back. Under the new law, however, the remaining cases challenging these business deals will be thrown out. The workers are worried they will no longer be able to seek redress.

The lawyers representing the workers are also concerned that the new law will increase the scope for corruption by eliminating oversight by third parties. “The moment I read the law,” said Khaled Ali, the lead lawyer and former head of ECESR, “I was more astounded than devastated.” The new law violates citizens’ constitutionally protected right to litigate and strips the State Council—the court that oversees challenges to such contracts—of its constitutionally-prescribed authority, he argued.

In contrast, the Egyptian business community, by and large, sees the new law as an essential ingredient to bring back investors—particularly from the Arab gulf—and relaunch the beleaguered Egyptian economy. Since the Arab spring, political instability and uncertainty have stymied foreign investment.

The post-revolution rulings reversing the privatisation of several companies have contributed to this unease.

Egypt averaged $8.8 billion in foreign direct investment (FDI) in the five years before 2011, according to the latest World Bank figures. By 2013, FDI had fallen to $3 billion.

The interim president, Adly Mansour, approved the investment law last April, shortly before the election in May of Abdel Fattah al-Sisi, the former defence minister. The law has two articles that transparency watch- dogs find objectionable and claim may lead to increased corruption. The first establishes that contracts for state businesses and real estate can be challenged only by the contract’s co-signatories, the state and the investor. The second article retroactively applies this rule to 11 cases that are still sitting in the country’s administrative courts, immediately closing them and upholding state contracts that may be crooked.

This new law eliminates all civilian oversight of government deals, according to Khaled al-Gamal, one of the ECESR lawyers challenging the law’s constitutionality. Third parties have historically been the only check on questionable contracts, he said.

One of the key demands by protestors during Egypt’s 2011 revolution was an end to the country’s endemic corruption. Mr Mubarak was infamous for his particular brand of crony capitalism.

In the final six years before the Egyptian revolution, corrupt and badly-negotiated oil and gas deals cost the Egyptian people $10 billion in revenue, according to a report issued jointly in March by the Egyptian Initiative for Personal Rights and Lon- don-based NGO, Platform. The situation today is just as bad, according to the report’s co-author, Mika Minio-Paluello of Platform. “We’ve seen a reassertion of the potential for corruption,” Mr Minio-Paluello said.

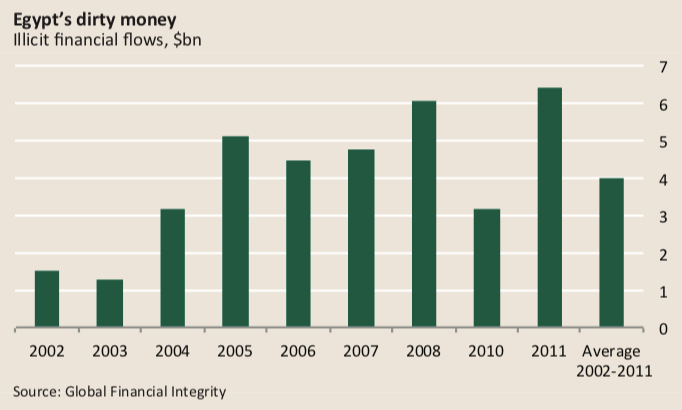

Despite Mr Mubarak’s removal, over $6 billion was squandered in 2011 due to corruption and illicit financial activities, according to Global Financial Integrity, a Washington, DC-based research organisation. This amounts to one-and-a-half times the state’s health budget for 2012-2013, according to an October 2013 ECESR report.

Egypt ranked 114 out of 177 countries in Transparency International’s 2013 Corruption Perceptions Index—a near failing score. Though some measures have been taken to curb graft and sleaze, such as a conflict of interest law that was passed in November 2013, the Egyptian government’s foremost financial oversight body—the Central Auditing Organisation—said in February that corruption is still costing the state billions of dollars. “There have been no real positive changes in terms of corruption,” said Heba Khalil, ECESR’s deputy director of research.

The Mubarak regime often awarded contracts to favoured investors—usually businessmen with close ties to the regime—at below market prices, according to Mr Minio-Paluello. These new company owners dismissed workers in droves, and in some cases, dismantled the company entirely and used the land for real estate development.

Workers and their lawyers challenged many of these deals in court before the revolution on charges that the contracts, and thus the state’s resources, were grossly underpriced. It was only in 2011, however, under the country’s interim military government, that a flurry of verdicts reversed many of these deals for the first time. The privatisation contracts for Omar Effendi, a department store chain, Tanta Flax, a flax seed and oil manufacturer, Shebin Textiles, the Al-Nasr Steam Boilers and Pressure Valve Company and Nile Cotton Ginning were reversed, the companies renationalised, and their factories handed back to the state.

Workers viewed the rulings as landmark victories because the rulings called for the companies to reinstate the employees with full benefits. The state has yet to imple- ment these verdicts, however.

But under the new investment law, workers and the judiciary would lose any oversight over these deals. “If you’re a worker in a factory, a normal citizen, or a public figure, you can no longer raise a case,” Mr al-Gamal said. “This is, of course, completely unconstitutional, because in the end this is public money. It’s the right of any citizen to object to the contract.”

The problem, however, is that too many contracts are challenged in court, scaring away foreign investors. Since 2011 international litigation against the Egyptian state has spiked, much of it instigated by angry investors after Egyptian courts renationalised their companies, according to ECESR’s November 2013 report. The same study states that Egypt ranks fourth worldwide in ongoing litigation in international courts: foreign investors have filed 13 lawsuits against Egypt in the World Bank’s International Center for Settlement of Investment Disputes (ICSID) since January 2011. The state’s lawsuits authority was quoted in the Al Ahram news- paper as saying that Egypt has faced 37 inter- national and domestic arbitration cases worth $14.3 billion in the last three years.

Before Egypt’s government invites Middle Eastern and other foreign investors to put their money back in the country, “you have to clear all the old arbitration cases and change the law to be more attractive to foreign investors,” says Hany Tawfik, head of the Cairo-based Egypt Private Equity Association, a non-profit dedicated to fostering investment and venture capital in Egypt.

If held constitutional, the new investment law would send a message that investors can once again safely put their money in Egypt without the fear of outside parties disrupting their deals, and without the burden of resorting to expensive and time-con- suming litigation to recover lost investments. The Egyptian government, faced with a ballooning deficit and state debt of 83% of its GDP, according to numbers released by the Central Bank of Egypt in March, is equally eager to bring back investors and sources of financing that have dried up since 2011.

The ECESR lawyers, however, claim the law will only lead to greater corruption and wasted state resources. The country’s highest constitutional court is expected to hear their case in October or November, though a date had not been set at the time of going to press.

Bringing these two sides together—developing a law that can achieve both over- sight and protect investors—is almost impossible. Businessmen and others who want to remove third-party challenges see it as a prerequisite for FDI. Workers and others interested in transparency insist on third-party oversight. “Don’t say that these lawsuits destroy the state’s relationship with foreign investors,” Mr al-Gamal warned. “It’s the opposite. They show that the state has a legal system, and that it defends its economy.”

While supporters of the law hope that it will improve economic instability, it may actually do the opposite, Mr Minio-Paluello cautioned. “Removing third-party challengers, that’s not a solution to instability,” he says. “A solution to instability would be… accountability.”

Others criticise the state for prioritising economic growth over scaling back corruption. “It doesn’t draw a very optimistic picture about possible change in the future,” ECESR’s Ms Khalil said. “It’s the same vicious cycle.”