The Conkouati-Douli National Park, a 795.500-hectare (7,955 km2) wonderland located in south-western Congo-Brazzaville on the border with Gabon, is on the verge of becoming a drilling site. A Chinese company is preparing to move in heavy equipment and manpower to launch intensive oil exploration following the granting of a permit by the Sassou Nguesso administration in February last year.

The move came barely six weeks after the government had accepted $50 million from the European Union (EU) and the Bezos Fund to protect its forests.

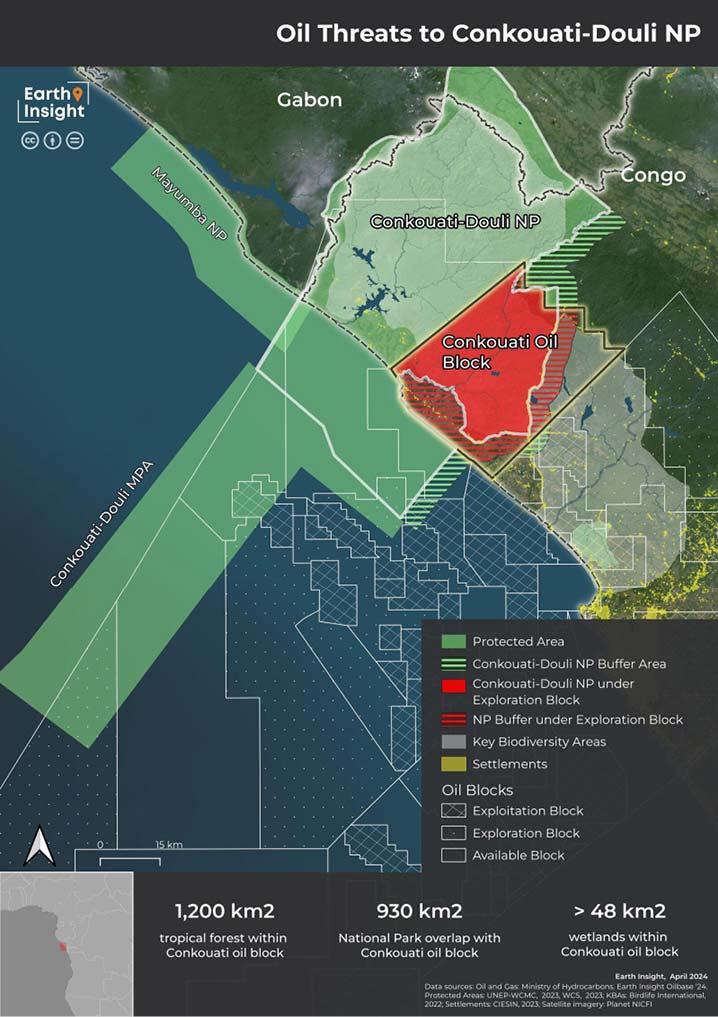

Now, 26% of the park’s surface area (1575,8 km2) is staring down the barrel of a gun of the joint venture between Congo Holding United, an 85% company owned by China Oil Natural Gas Overseas Holding Ltd, in which the government has a 15% stake through the state-controlled Société Nationale des pétroles du Congo (SNPC).

Earth Insight, which alongside Greenpeace and 13 local NGOs last year called on donors to suspend funding for park conservation until the oil and gas permit was revoked, said the Conkouati oil exploration permit covers 26% of the Conkouati-Douli National Park and more than 1,000 km2 of intact rainforest.

Created in 1999, the park is the country’s most biodiverse protected area, recognised as a Ramsar Site and registered on the indicative list of UNESCO World Heritage. The facility, which has a marine section of 412,195 hectares, protects more than 5,000 km of coastal, marine, and forest ecosystems where the Congo’s tropical rainforest meets the Atlantic Ocean.

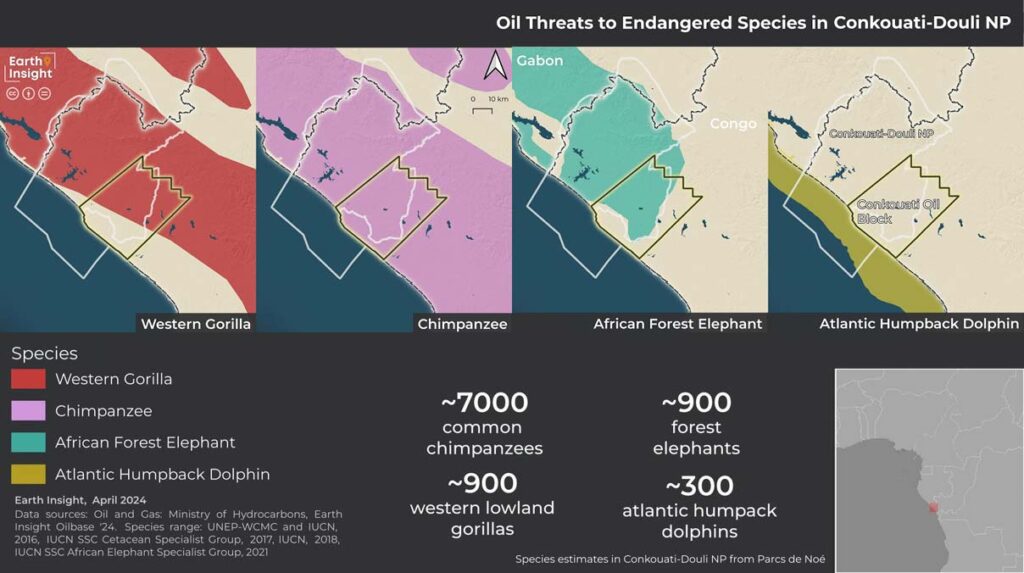

Nevertheless, it remains unclear what will happen to its residents, a long list of which comprises, among others, gorillas, chimpanzees, hippos, elephants, buffaloes, Nile crocodiles, sea turtles, manatees, dolphins and whales, river hogs, and a multitude of migratory birds. Nearly 7,000 indigenous people live in 31 villages on the park’s edge, mostly fishermen from the coast who have been established there since the 13th century.

The campaigners are worried that prospecting oil and gas will threaten the survival of the park, which is home to key endangered wildlife species, including the western lowland gorilla, the leatherback turtle, and the forest elephant.

Despondency and anger have been mounting in Pointe-Noire, Congo’s second-largest city, located nearly 130 km from the park. Many residents accuse local and international environmental organisations of doing little to stop the government-China joint venture from “selling Africa to the highest bidder”. “They were just making noises, nothing much”, Mesmin Matondo told Africa in Fact by telephone. “I think they should have taken concrete actions, like sitting down with the government and the Chinese company, to request assurances that the park’s occupants (people, flora, and fauna) will not be harmed.

“By engaging in a dialogue with them, they could have reminded the government that its action constitutes a violation of a 1999 presidential decree establishing the park, which states that exploitation permits can only be granted within areas designated as ‘eco-development zones’, but that extractive activities might not be allowed within the 5 km buffer zone on the south and east sides of the park.”

Claire Mavoungou, an environment student who was only 10 years old when her father took her and the entire family to visit the national park, describes the government’s granting of the oil permit as an unspeakable act of betrayal and treason. “My father would be turning in his grave,” she said. “I think he knew that the park [was] precious because he used to say something like, ‘This park is a treasure that needs to be protected at all costs. I hope in the future the authorities will not fall for the temptation of digging it up to find what is hidden underneath.’ I was young and did not know what he was referring to, but now I know. It’s treason, period.”

Mavoungou questioned the efficacy of environmental organisations’ efforts. “I don’t think they tried hard enough,” she said. “We are disappointed in them; we really thought the DRC scenario would be repeated here.”

She was referring to the DRC government’s decision in mid-October last year to concede defeat by cancelling, at least temporarily, a major auction of rights to drill for oil and gas across the country, including in highly sensitive parts of the Congo Basin. The Bureau of Investigative Journalism (TBIJ) revelations about the auction process, plagued with apparent preferential treatment and backroom deals, might have influenced the decision.

However, that looks highly unlikely on the other side of the Congo River, where the government, determined to increase the production of fossil fuels at all costs, refuses to budge, ignoring calls by the environmental community to stop the destruction of one of Africa’s most amazing natural jewels.

To show that it meant business and to speed up the process, Congo Holding United announced in early October that it would invest $150 million over the next three years to accelerate the drilling of the Conkouati-Koui and Nanga III wells.

“To increase national production, we must be able to capitalise on proven reserves. We want to develop the free fields so that production can increase and the government can have additional room to manoeuvre and resolve the problems of the Congolese,” local media reports quoted Fulbert Dzimbe, director-general of Congo Holding United, as saying.

But speaking from the capital, Brazzaville, a civil servant who wished to remain anonymous wondered what problems President Denis Sassou Nguesso would solve by allowing China to destroy the Conkouati-Douli National Park, problems he had failed to solve during the nearly 40 years he has been in power.

“We started exporting oil a very long time ago, but we still have nothing – no stable electricity and water supply, no adequate health system. Our youth have no jobs, and we still earn peanuts as salary. Corruption persists, and poverty is rising. I’m not sure what Mr Dzimbe says about room for manoeuvre and resolving the problems of the Congolese. It’s called demagogy.”

Like his countrymen, the civil servant deplored the defeatist attitude of international NGOs, which he accused of throwing in the towel without a fight. “They should have engaged in a dialogue with China to remind them that what it is doing to Africa is unfair,” he said.

The self-proclaimed Global South leader, China, often describes its partnership with the continent as a “win-win” process. Still, its local and international critics and many ordinary Africans disagree, saying its activities amount to neocolonialism. They complain it has not done enough to improve the lives of millions of Africans still trapped in poverty.

Claude*, an unemployed university graduate who also spoke to Africa in Fact, wondered why China spoke of a win-win partnership while one of its companies was preparing to tear apart a national park, risking the lives of endangered species and indigenous people in the process.

Another concerned citizen, Brice*, who echoed the sentiments of other Congolese interviewed, said: “These Chinese people are unpredictable. They can go to the Conkouati for oil and gas but end up cutting trees to make timber or digging up to look for diamonds and gold. I really predict an enormous environmental disaster in and around the park. It’s not right; someone needs to stop China from destroying our lands and plundering our natural resources.”

The International Institute for Environment and Development (IIED), a London-based NGO, said in a recent report that while Chinese investment and trade was having a huge impact on African forests by providing steady jobs and incomes for local communities and contributing towards decent forest management, in other instances forests had suffered and people’s lives changed for the worse.

However, Mariella Di Ciommo, Associate Director for Europe and Africa at the Netherlands-based European Centre for Policy Development Management (ECDPM), told Africa in Fact that from a Chinese perspective, the primary interlocutor of China’s government was the Congo-Brazzaville government. “China tends not to take a position on internal matters, including conflicts between environmental/indigenous matters and economic exploitation or certain areas.

“I gather this has been changing in the last few years, though, as China has become more sensitive to protests and a bad reputation linked to similar cases in such contexts. This is because this has caused pushback on Chinese practices and led to the renegotiation or even cancellation of some projects.

“As a result, it has started to follow more international norms and standards rather than rely on national legislation, although in an inconsistent manner. One factor is the extent of the pushback they receive (and possibly also the economic stakes at play).”

Poorva Karkare, Policy Officer at the ECDPM, insisted that China-Africa engagements were as much shaped by African stakeholders and their demands as by the Chinese. “As long as the Chinese get a licence on land the government itself has auctioned, then appealing to Chinese morality can only go so far. It is the government’s responsibility in Brazzaville to refrain from putting the land on auction in the first place to protect biodiversity. It is important to understand the agency [involved in] the African side in this story.

“Secondly, the Congolese government is not giving this to the Chinese for free; they are generating state revenues from the deal. The question is whether what they are getting is enough when accounting for the social and environmental costs. This is a larger question that many countries are dealing with. In many cases, the problem is that not all costs are visible or equally priced.

“What goes missing in this framing of China acting (whether recklessly or not) is that for the Congolese government, revenues are needed to run the country. These revenues can come from sales of licences, among other things. The protection of biodiversity, even though very desirable, costs money and has too little revenue generation capacity.

“In such a scenario, the loss of biodiversity or the rights of indigenous peoples may be seen as dispensable, or simply the price to pay for economic gains that come from the sale of licences.”

Kinshasa-born Issa Sikiti da Silva is an award-winning freelance journalist. Winner of the SADC Media 2010 Awards in the print category, he has travelled extensively across the African continent. He lived in South Africa for 18 years, where he worked for 10 years as a journalist before leaving for West Africa, and later to East Africa, to work as a foreign correspondent. He is currently based in Dakar, Senegal.