It is now commonly accepted that the world is moving towards an urban future, and with African (and Asian) cities set to account for 86% of the world’s urban population growth, we are faced with the challenge of how best to plan and develop for this reality.

Urbanisation brings with it multi-dimensional shifts, and those shifts come with their own problems. One such problem is how we intend to feed this burgeoning urban population, considering that today, nearly 60% of Africans are either moderately or severely food insecure. You cannot begin to discuss food security without discussing urban food systems in Africa, as they hold lessons and the potential for a new way of thinking about food in our cities.

Food systems are complex and difficult to untangle at times. They operate at multiple scales, in multiple geographies, and rely on multiple networks, systems, and infrastructures to function. Food security in Africa presents what could be described as a wicked problem. Increased investment in technology and agricultural processes in the past 60 years has done very little to reduce food insecurity on the continent.

Tackling this wicked problem requires a systematic approach, one where we can identify possible leverage points in the system, an approach championed by renowned systems thinker Donella Meadows. Within this approach, a deep understanding of the system and the thresholds for change that exist at any point is required.

Food security as a system can be understood through its six pillars: access, availability, utilisation, stability, agency, and sustainability. All of these pillars present possible leverage points and are the topics of many articles on food security, but I would like to zoom in on “access” as a pillar and possible leverage point, and its spatial manifestation in our urban environments that are morphing our access and relationship to food, and the dangers they present.

To borrow from logistic business speak, food access often represents the “last mile” of a food system, the contact point with the consumer, and one that is spatialised either through access points such as grocery stores or food deliveries. This last mile is widely accepted as the most difficult part of any logistics business and a potential failure point, and the same can be said of food access points. They require close attention if we are to seriously address our food security challenges.

As one of the more developed economies on the continent, South Africa offers us insights into how there has been a shift in food access that has been underpinned by our flawed development models. The spatial restructuring of consumption within South Africa’s urban centres has widespread implications.

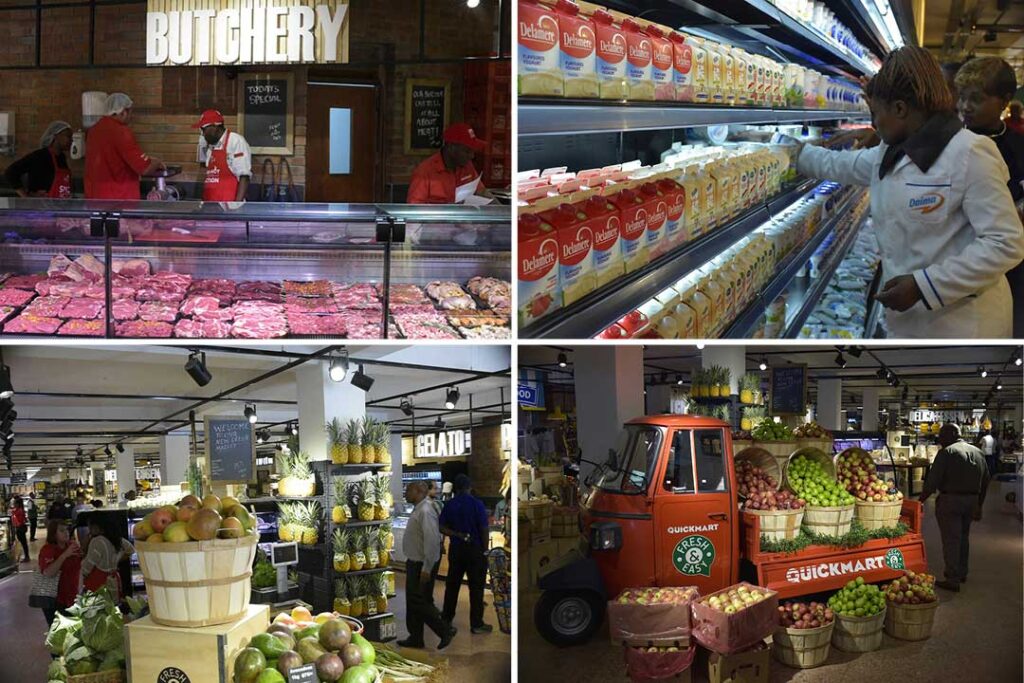

South Africa’s food access landscape has shifted dramatically in the past three decades. In 1992, approximately 90% of all food in South Africa was purchased from small-scale neighbourhood stores, informal vendors, local fruit and vegetable shops, and spazas, and only 10% was purchased through large supermarket chains. By 2017, the landscape had been completely altered, with supermarkets now accounting for as much as 75% of all groceries sold in the country, a number that makes it the highest in the world. During this time, South Africa has built and continues to build an extraordinary number of supermarkets, anchored within the shopping mall typology that punctuates not only the suburbs of the country but increasingly its townships and rural areas.

The result of this proliferation is the decline of the diverse access points that underpinned food access in communities, such as neighbourhood stores and vendors, who formed key economic mainstays of community life. This shift in landscape has had significant implications for food security because it has undermined an important part of communities that allows them to access food closer to home, on a scale necessary, and using credit systems built on trust developed over time.

The social and cultural underpinnings of these food access points play a vital role in how many people, especially in more economically vulnerable spaces, are able to access food. The concentration of supermarkets as dominant points of food access has inadvertently generated a food system that undermines food security.

Small-scale stores are more closely aligned with the economic realities of communities than supermarkets. While supermarkets offer food at overall lower price points per unit, their unit sizes are often too large for the economically vulnerable to afford. The operating times of supermarkets are also often not aligned with the times most communities return from work. The spatially concentrated nature of shopping malls also means there has been an increase in distance between consumers’ homes and the supermarkets.

This expansion and concentration of supermarkets are the result of two contributing factors. The first is the financialisation and growth of consumerism in the South African economy, which started in the early 1990s. What this did was create demand in the economy for low-risk, high-yield investments, and property, which has long been seen as the holder and creator of wealth, became an opportune outlet of which developers were more than ready to take advantage. There was also a demand boost due to the increase in credit made available to consumers. With the flow of capital and the growth of the middle class, shopping malls and supermarkets became the symbols of modernisation and development in the country.

The relationship between development and shopping malls still has a strong hold on our public psyche, so much so that the model is being replicated across the continent. The growth of shopping malls in Kenya and Ghana, often anchored by South African retail giants such as Shoprite or Mass Mart’s Game stores, is an example.

The framing above serves to highlight the interlinked dependency of urban food systems and urban governance, particularly urban planning. One could argue that local governments have no power to decide on food supply, but it becomes clear that through their inaction, either through policy or planning, they have a tangible impact on food systems. Recognition of this gap in urban governance presents a potential leverage point through which we can imagine food systems that are more rooted in African practices and ways of life and that are able to respond to the specific needs of consumers.

To start reimagining a food system for African cities that is rooted in localised social and cultural practices, it is important to recognise current spatial forms of food access not only as a stop-gap and unmodern typology, but as what they tell us about the logic of community. They can provide a good basis from which we can develop Afrocentric models of modernity and urban governance with respect to food.

I want to draw on two examples from different parts of the continent. The first is the spaza shop, a typology that punctuates South African townships and exists in similar forms in cities across the continent. Spaza shops offer a community-based and flexible food access point that responds to the needs of its immediate community, whether through the products they stock, the unit sizes they sell, or the informal credit system they offer to trusted members of the community. Their resurgence of late signifies a clear demand for these more localised access points, and their contribution should not have to exist outside of formal urban planning systems.

On the eastern coast of the continent, Kibandas (which are small, usually informal outdoor restaurants) not only punctuate the poorer parts of Nairobi but are a common sight in the wealthier neighbourhoods of Westlands, Lavington, and Kileleshwa as well. These informal roadside restaurants are popular even among professionals who work in these areas. It is not uncommon to see workers in suits sitting at one of the wooden huts, enjoying a plate of ugali, sukuma wiki, and some goat meat during lunch.

These neighbourhoods are populated by some of the most popular shopping malls in the city, yet the presence and popularity of Kibandas remain strong and are growing. Despite this, they are not a part of urban planning and future visions of the city; they are instead seen only as a subaltern practice rather than having the potential to play an important role in Nairobi’s urban food system planning.

It is clear that food systems have to be part of future urban planning and urban governance, especially relating to food access. There is a significant gap in policy, practice and research in this space, but it holds great potential to shift the mental models of development that currently hold sway and avoid a path dependency that might be detrimental to food security on the continent.

We have to re-imagine new forms of development and modernisation that centre on localised practice rather than undermining them. This reimagination then needs to inform our urban planning processes, which themselves need to be re-imagined to be more fit for purpose in challenging contexts across the African continent.

Tshepo Mokholo

Tshepo Mokholo is an urban practitioner, designer, writer, and researcher based in South Africa. He has worked on design and research projects across the continents including Kenya and Rwanda. He holds an Honours degree in Architecture from the University of Pretoria and is currently a Master’s student in Southern Urbanism from at the African Centre for Cities, where his research is exploring alternative development models, using an analysis of township food systems as an entry point.