The adage “what gets measured, gets managed” has never been more relevant to Africa’s development. Across the continent, data infrastructure remains underdeveloped compared to other regions, and sub-national data on key socio-economic and political issues is even more scarce – especially in sub-Saharan Africa, often referred to as the “data desert”.

While better data exists at the country level and offers a broad overview, it often obscures sub-national disparities that impact urban service delivery, transportation, resource allocation, and socio-economic and political outcomes. Moreover, existing data is often collected inconsistently, creating gaps in time-series data that are vital for identifying trends.

This lack of granular data creates a gap that impedes meaningful governance reforms and evidence-based policy interventions. African local governments often face difficulties providing adequate water, sanitation, waste management, and electricity to their growing urban populations. As the primary point of contact between citizens and the state, they also shape public perception of governance. Without robust data and adequate technical capacity, these governments operate in the dark, making it impossible to achieve governance improvements or implement effective policies.

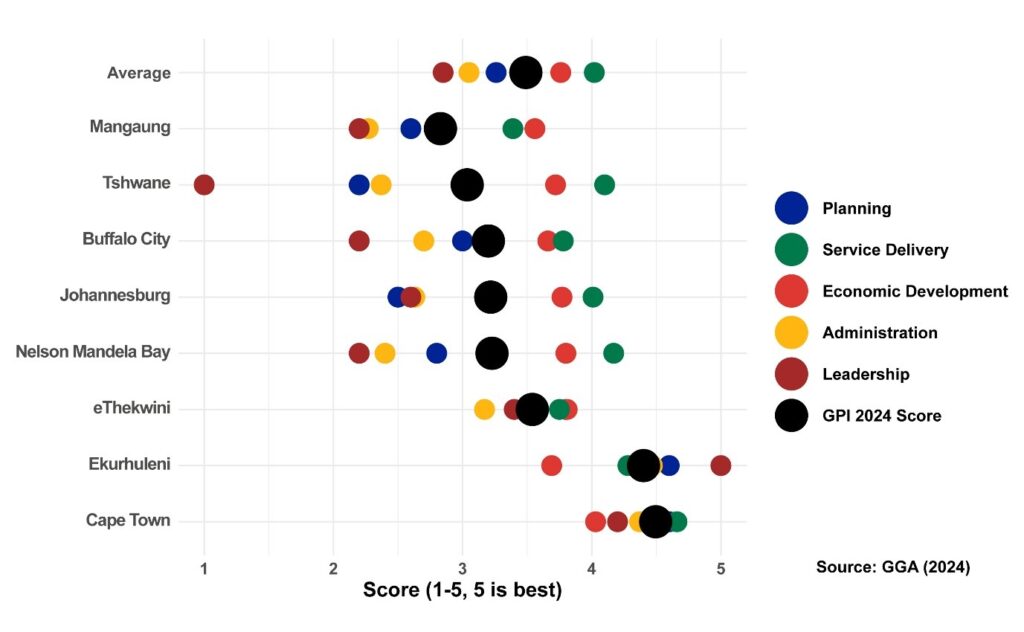

Recognising this, Good Governance Africa (GGA) has launched a project to profile African cities, beginning with those in the Southern African Development Community (SADC). This is an important step toward developing performance indicators for African cities, akin to GGA’s Governance Performance Index (GPI) in South Africa. The GPI evaluates and ranks South African local municipalities based on their governance efficacy, employing an array of local data sets. The latest version was released in March 2024.

As local government expert Ian Palmer rightly notes, accurate, comprehensive, and actionable data is important for informed decision-making and sustainable urban development. He highlights that tackling governance challenges, strengthening technical capacity, and ensuring financial sustainability depend on detailed data-driven insights into urban dynamics. Improved sub-national data collection and analysis can enhance the planning, monitoring, and management of urban growth and service delivery. It can also bridge the gap between policy design and lived realities and create more inclusive and responsive governance across the continent.

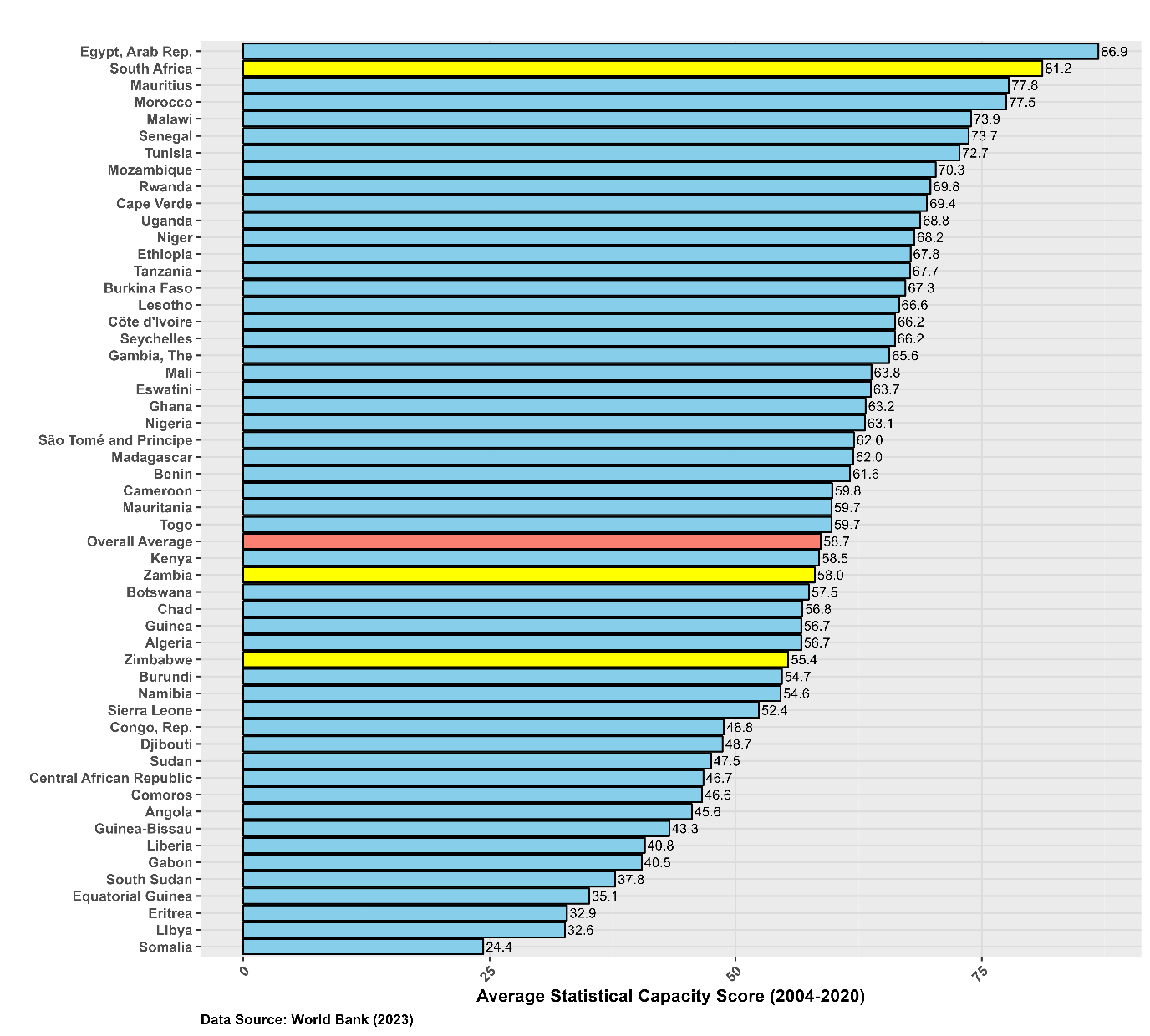

However, Figure 1 reveals the challenges that some African countries face in developing their statistical systems. The World Bank’s Statistical Capacity Indicator provides a composite score assessing a country’s ability to collect, analyse, and disseminate high-quality data about its population and economy. The index evaluates areas such as methodology, data sources, and the periodicity and timeliness of reporting on a scale of 0 (lowest capacity) to 100 (highest capacity).

Countries like Egypt, South Africa, and Mauritius lead the continent in statistical capacity, while countries such as Eritrea, Libya, and Somalia underperform. In the SADC region and sub-Saharan Africa, South Africa, home to cities like Johannesburg and Cape Town, ranks highest on this indicator over the observed period. In contrast, Zambia and Zimbabwe, which house Lusaka, Harare, and Bulawayo – cities included in GGA’s SADC city profiling sample – fall below the overall African average of 58.7.

The situation in Zimbabwe and Zambia shows the need for better data infrastructure. In Harare, for instance, the Harare City Council (HCC) has acknowledged that the lack of reliable data often undermines decision-making and impedes efforts to improve water service delivery, a critical issue given the frequent water shortages and water-borne diseases that residents face. Similarly, Lusaka struggles with inadequate data systems, making it difficult for policymakers to address urban challenges such as housing, transportation, and waste management.

Contrast this with South African cities with better (open) data infrastructure and mechanisms. Johannesburg, for example, benefits from a well-established data system supported by government agencies such as Statistics South Africa, the Auditor General’s office, and South African government departments like the Department of Water and Sanitation. It also has better statistical capacity and mechanisms than cities like Lusaka and Harare based on GGA’s city profiling exercise. This robust data ecosystem in South Africa has facilitated the development of sub-national measures of governance and economic performance like GGA’s Governance Performance Index (GPI). However, South Africa’s stronger performance may also reflect factors like economic size, governance quality, and overall institutional capacity.

Figure 2 further illustrates the differences in statistical capacity between Zimbabwe, Zambia, and South Africa. Over the years, South Africa has maintained higher statistical capacity scores. In contrast, Zimbabwe and Zambia have struggled to maintain stable and reliable data systems. Zimbabwe has recorded the most improvement over the years. Still, the erratic scores in the country may highlight its challenges with political instability and economic crises (e.g., the hyperinflation in 2008), which may have disrupted its ability to collect and manage data. Zambia’s relatively stagnant performance demonstrates the need for renewed investment and capacity-building in its statistical systems.

The lack of reliable data can impede effective governance and service delivery. For example, without accurate population data, it becomes difficult for city authorities to plan for adequate housing, health care, transportation and other social services.

The World Bank notes that quality data is essential for all stages of evidence-based decision-making, including monitoring social and economic indicators, allocating political representation and government resources, guiding private sector investment, and informing the international donor community for programme design and policy formulation. Sub-national data can help policymakers identify and address the needs of different communities by providing a more granular understanding of local dynamics.

The GPI’s success in South Africa demonstrates the importance of sub-national data. The GPI empowers citizens to hold their local governments accountable, provides policymakers with the insights needed to improve service delivery, and helps local municipalities identify strengths and areas needing improvement overall.

Figure 3 shows the 2024 GPI scores for South African metropolitan municipalities, with Cape Town leading on most measures and Mangaung ranking the lowest on the GPI. Replicating this model in other African countries could yield similar benefits, but it requires a concerted effort to build and strengthen data infrastructure at the sub-national level.

One way to achieve this is through partnerships between governments, research institutions, international development organisations, and other stakeholders. These partnerships can provide the technical and financial support needed to develop robust data systems and build local capacity for data collection and analysis. Moreover, leveraging technology can help overcome some of the challenges associated with data collection in resource-constrained environments. Mobile surveys, satellite imagery, and data analytics platforms can provide cost-effective solutions for collecting and analysing sub-national data.

Artificial intelligence (AI) can also provide solutions for addressing data gaps and improving urban planning in African cities. Machine learning can, for example, analyse satellite imagery to track informal settlements and predict infrastructure needs, while AI-driven natural language processing tools can extract insights from citizen feedback. Predictive analytics can also help city officials anticipate and address service delivery challenges like water shortages and traffic congestion.

However, AI adoption requires investment in digital infrastructure and technical capacity to ensure that local governments can effectively use such tools and insights. These technologies are also not one-size-fits-all solutions for all local governments. Their effectiveness depends on each local government’s unique governance structures, resource availability, and technical expertise. Policymakers and stakeholders must tailor their approaches to the specific needs and constraints of different municipalities and their members rather than adopting a blanket strategy.

Further, several underlying challenges must be addressed for digital solutions to be viable. Frequent power outages disrupt ICT operations, while the digital divide (particularly at the local government level) limits access to necessary tools and training. Without reliable infrastructure and inclusive capacity-building efforts, the benefits of AI, ICT, and data systems risk being concentrated in a few well-resourced local governments.

Another important consideration is the need for standardisation and comparability of data. As GGA’s city profiling exercise has shown so far, existing data is often incomparable across African cities. This lack of comparability undermines the development of regional benchmarks and performance indicators, making it difficult to track progress and identify best practices across the continent.

The city profiling initiative is an important step toward addressing these challenges and fostering more robust and responsive local governance in Africa through data. It seeks to develop standardised data collection and reporting frameworks for African cities, among other things. This is useful to urban service providers, national governments, and international development agencies that regulate and support local authorities.

City residents also benefit from easy and open access to information on the development circumstances of their cities, empowering them to participate in governance and hold authorities accountable. As Baratang Miya, chief executive of Girlhype Coders Academy, highlighted in March last year, “We really need data that speaks to Africa itself, and the case for open data means we are empowering citizens and at the same time encouraging innovation and efficiency, and not using data that is inaccurate.”

The overarching goal of GGA’s cities initiative is to promote sustainable urban development by enabling data-driven decision-making, strengthening urban resilience, and improving citizens’ quality of life. As part of this effort, city profile reports are being developed to assess urban development and service provision across individual African cities and identify challenges and opportunities.

An African cities database is being established to enhance urban governance further, consolidating data on service provision and municipal finance. This database will support policy evaluation, accountability, and strategic planning, ensuring decision-makers can access reliable and up-to-date information. Regular monitoring of key indicators will also be essential in tracking progress in service delivery and aligning with global and regional development frameworks, such as the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and the African Union’s Agenda 2063.

Without reliable sub-national data, African cities may face heightened challenges in addressing the needs of their rapidly growing populations. Policymakers will lack the insights needed to design effective interventions, and citizens will be deprived of the information they need to hold their governments accountable. On the other hand, investing in sub-national data can create innovation, economic opportunities, and social progress. Still, these need to go hand in hand with improvements in governance quality, financial management and capacity, internet connectivity and overall ICT infrastructure and technical capacity.

This also depends on effective data governance, which ensures the quality, security, and accessibility of sub-national data. Many African countries struggle with fragmented data ownership, privacy concerns, and a lack of coordination between government agencies. Establishing clear regulatory frameworks and oversight mechanisms can enhance transparency, promote interoperability, and ensure that data serves public interest objectives. Open data initiatives, if well-governed, can empower citizens, researchers, and businesses.

In conclusion, sub-national data matters for Africa. It is a vital tool for understanding and addressing the challenges facing African cities and fostering more inclusive and responsive governance. South Africa’s success in maintaining high statistical capacity allows for developing sub-national indicators like the GPI, provides a model for other African countries, and necessitates GGA’s cities initiative. It demonstrates how investing in data infrastructure and developing performance indicators can yield benefits. However, replicating this across other African cities will require investment, capacity-building, tailored approaches, and collaboration among multiple stakeholders.

Nnaemeka is a Senior Data Analyst at Good Governance Africa. He holds a Master’s degree in e-Science (Data Science) from the University of the Witwatersrand, funded by South Africa’s Department of Science and Innovation. Much of his research explores socio-political issues like human development, governance, bias, and disinformation, using data science. He has published research in scholarly journals like EPJ Data Science, Politeia, the Journal of Social Development in Africa, and The Africa Governance Papers. He has experience working as a Data Consultant at DataEQ Consulting. He has also taught at the Federal University, Lafia (Nigeria) and the University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg (South Africa).