Over a century of deeply racist Western literature continues to influence notions of ‘blackness’ and what it means to be an African

When I wrote my master’s paper at the Graduate School of Journalism at Columbia in the 1990s I showed that the literature of 18th century demonisation of Africa—in order to

justify the conquest and colonial rule eventually formalised with the 1884 Berlin Conference—has a strong and enduring influence on contemporary Western writings about Africa.

European so-called explorers used the word “tribesmen” interchangeably with “savages”.

Here’s what Samuel Baker, author of “Albert N’Yanza, Great Basin of the Nile”, (1866), said about African “tribesmen”: “I wish the Black sympathiser in England could see Africa’s innermost heart as I do, much of their sympathy would subside … Human nature viewed in its crudest state as pictured among African savages is quite on a level with that of the brute, and not to be compared with the noble character of the dog.”

The German traveller, Georg Schweinfurth, also warned in “Heart of Africa”, (1873) that: “The first sight of a throng of savages, suddenly presenting themselves in their naked nudity, is one from which no amount of familiarity can remove the strange impression; it takes abiding hold upon the memory, and makes the traveller recall anew the civilisation he has left behind.”

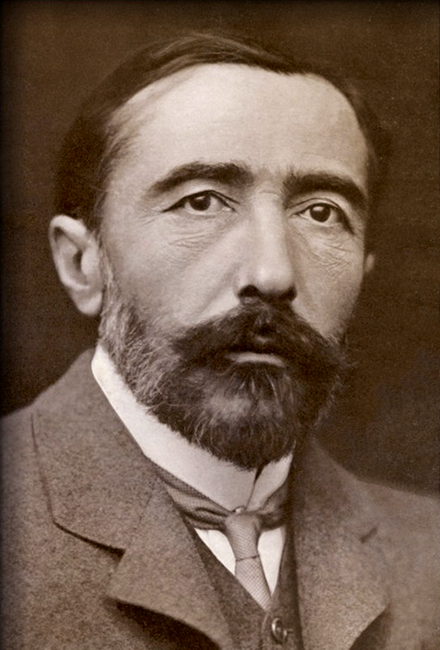

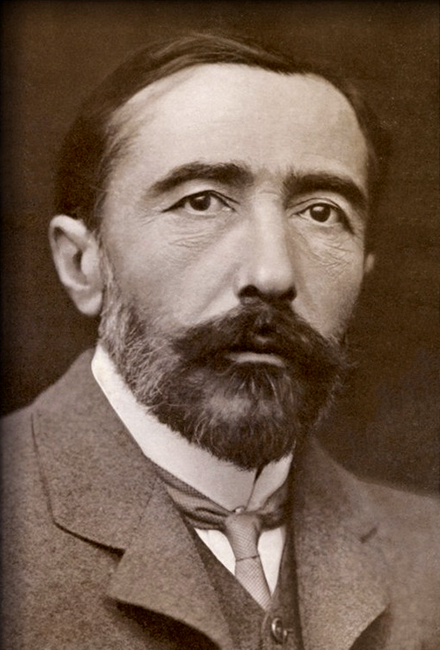

The “tribalised” image of Africans has endured thanks to passages like this one from Joseph Conrad’s celebrated “Heart of Darkness” (1902): “We were wanderers on a prehistoric earth, on an earth that wore the aspect of an unknown planet. We would have fancied ourselves the first men taking possession of an accursed inheritance, to be subdued at the cost of profound anguish and of excessive toil. But suddenly, as we struggled around a bend, there would be a glimpse of rush walls, of peaked grassroofs, a burst of yells, a whirl of black limbs, a mass of hands clapping, of feet stamping, of bodies swaying, of eyes rolling, under the droop of heavy motionless foliage. The steamer toiled along slowly on the edge of a black and incomprehensible frenzy.”

The book is loved by millions of Europeans—and Africans—yet Chinua Achebe correctly concluded that Conrad was “a thoroughgoing racist” in “Hopes and Impediments” (1988). Conrad’s Africa shaped the mindset of professional journalists who started covering Africa in the 20th century.

European enforcers of colonial regimes exploited this “tribal” perception of Africa, as demonstrated when Albion Ross, a New York Times correspondent, interviewed Gabriel Teixeira, governor general of Portuguese Mozambique. Ross’s article was published on April 22, 1954 under the headline “Portugal Accepts African Equality”.

“We do not believe in superior and inferior races,” the governor told Ross. “The black man in Africa is simply where the white man began thousands of years ago. You cannot rush that sort of thing.”

“A native vote is absurd,” Teixeira added. “These people’s grandfathers were sometimes cannibals. How do they vote? What do they vote for?” Ross did not challenge any of the governor’s assertions nor interview Africans to hear what they had to say.

There is no question that the personal prejudices of the reporters and editors were reflected in the stories published about Africa, as I discovered from letters they exchanged that I found in the Times’ archives.

“I’m afraid I cannot work up any enthusiasm for the emerging republics,” Homer Bigart, a famous New York Times reporter wrote in a letter to his editor Emanuel Freedman from Ghana in early 1960.

“The politicians are either crooks or mystics. Dr Nkrumah is a Henry Wallace in burnt cork. I vastly prefer the primitive bush people. After all, cannibalism may be the logical antidote to this population explosion everyone talks about.” (Henry Wallace was an American segregationist politician who wanted black people deported to Africa.)

Bigart’s favourite terms for describing Africans in his articles were: “barbaric”, “macabre”, “grotesque”, and “savage”. Typical of the prose that he and Freedman enjoyed was an article by Bigart, published on January 31, 1960 under the headline “Barbarian Cult Feared in Nigeria”.

“A pocket of barbarism still exists in eastern Nigeria despite some success by the regional government in extending a crust of civilisation over the tribe of the pagan Izi,” Bigart wrote.

He added, “A momentary lapse into cannibalism marked the closing days of 1959, when two men killed in a tribal clash were partly consumed by enemies in the Cross River country below Obubra. Garroting was the society’s favored method of execution. None of the victims was eaten, at least not by society members. Less lurid but equally effective ways were found to dispose of them …”

Freedman, encouraged this type of “journalism”, writing to Bigart in a letter dated March 4, 1960: “This is just a note to say hello and to tell you how much your peerless prose from the badlands is continuing to give us and your public … By now you must be American journalism’s leading expert on sorcery, witchcraft, cannibalism and all the other exotic phenomena indigenous to darkest Africa. All this and nationalism too! Where else but in the New York Times can you get all this for a nickel?”

When the Times’ editors felt articles lacked the “tribal” element, they simply concocted them.

After Lloyd Garrison, a New York Times correspondent who was based in Nigeria read the version of his article published on May 31, 1967 he sent off a letter dated June 5, 1967 complaining to the editors about a fabrication added to his story: “The reference to ‘small pagan tribes dressed in leaves’ is slightly misleading and could, because of its startling quality, give the reader the impression there are a lot of tribes running around half naked … Tribesmen connote the grass leaves image … Plus tribes equals primitive, which in a country like Nigeria just doesn’t fit, and is offensive to African readers who know damn well what unwashed American and European readers think when they stumble on the word …”

Sometimes Western writers play off different ethnic groups against each other. This was certainly the case during the inter-ethnic war between the Hutu majority and Tutsi minority in Rwanda after Tutsi exiles backed by Uganda invaded on October 1, 1990. In “Rwanda’s Aristocratic Guerrillas” published in the New York Times Magazine on December 13, 1992, Alex Shoumatoff wrote that Tutsis were “refined” while Hutus were “short, stocky” and “broad nosed”.

“In the late 19th century,” Shoumatoff continued, “early ethnologists were fascinated by these ‘languidly haughty’ pastoral aristocrats whose high foreheads, aquiline noses and thin lips seemed more Caucasian than Negroid, and they classed them as ‘false negroes’. In a popular theory of the day, the Tutsis were thought to be highly civilised people, the race of fallen Europeans, whose existence in Central Africa had been rumoured for centuries.”

It is not difficult to imagine which side the article intended for Western readers and policy makers to empathise with and favour in the war. The war dragged on for four years. Then suddenly on April 6, 1994 the conflict turned into apocalyptic massacres after the plane carrying Rwanda’s President Juvenal Habyarimana—and his Burundian counterpart Cyprien Ntaryamira—was shot down, killing both.

The genocidal killings claimed an estimated 800,000 to one million lives of Tutsis and Hutus. In an article about the massacres in Rwanda, Time magazine in its April 25, 1994 edition claimed the killings were fuelled by “tribal bloodlust and political rivalry”.

Where do we stand when it comes to the T-word in this the 21st century? What the late Ugandan scholar and author Okot p’Bitek wrote about the word “tribe” in “African Religions in Western Scholarship” (1970) remains true. “Western scholarship sees the world as divided into two types of human society,” p’Bitek wrote, “one, their own, civilised, great, developed; the other the non-western peoples, uncivilised, simple, undeveloped. One

is modern, the other tribal.”

This is the same logic that applied when the international community basically stood by during the Rwanda massacres; presumably because Africans were simply quenching their “tribal blood lust”, to borrow Time magazine’s words.