Togo’s health workers: no reason to stay

Too many of this West African nation’s doctors and nurses work abroad

by Blamé Ekoué

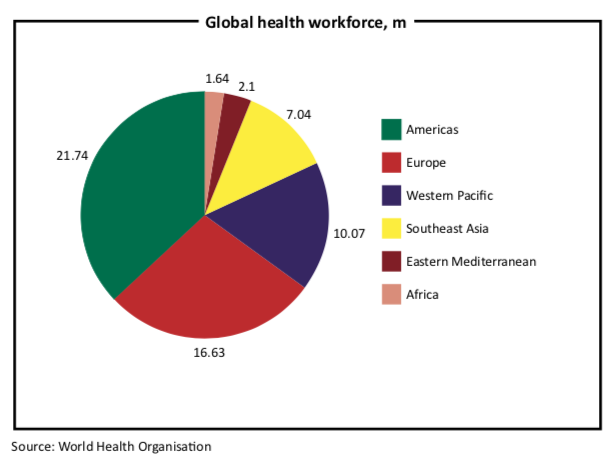

Africa is suffering from a major shortage of qualified doctors, nurses and other health workers. In its last global survey of health workers in 2006, the World Health Organisation (WHO) counted 1m doctors, nurses and midwives in 46 African countries, and a reported shortage of more than 800,000 in 36.

Sub-Saharan Africa was dealing with 25% of the global disease burden but had only 1.3% of the world’s health workers and less than 1% of the world’s financial resources for health in 2009, according to a study published in Ethnicity & Disease by Saraladevi Naicker of South Africa’s University of the Witwatersrand and three other academics from Ghana and the United Kingdom.

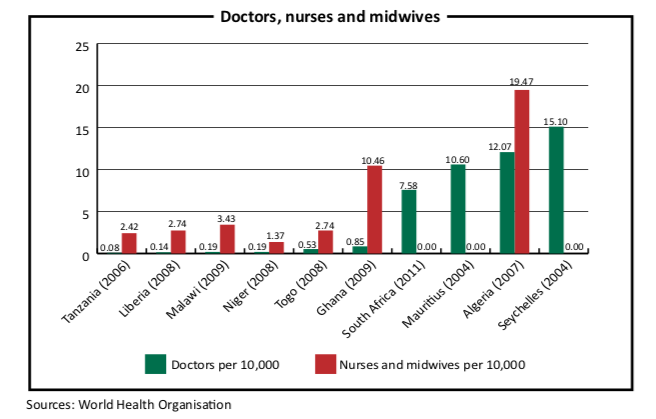

In Togo, a tiny West African nation, the dearth of health workers is acute. Doctors and nurses are leaving Togo in droves, moving to other African countries or to Europe. They grumble about Togo’s poorly equipped medical facilities and complain that they are underpaid and can earn more abroad. The result is a country that is unlikely to meet its health-related Millennium Development Goals (MDGs). To reach these goals will require at least one doctor for every 10,000 persons, according to Togo’s health ministry. This would require doubling its current crop of doctors.

When seeking medical help, Togo’s 6.6m residents can turn to only 349 physicians in the country (or 0.53 per 10,000) and 1,816 nurses and midwives (2.74 per 10,000), according to 2012 WHO statistics. The WHO standard is 25 doctors, nurses and midwives per 10,000, or at least one of these medical professionals for every 400 persons. Neighbouring Ghana has nearly six times the number of doctors, 2,033 (0.85 per 10,000) and 24,974 nurses and midwives (10.46 per 10,000), according to the WHO. When compared to Europe, Africa’s 1m doctors, nurses and midwives (13 per 10,000) lag far behind Europe’s 8.9m (109 per 10,000).

“The lack of training centres and equipment and low salaries are the main

reasons behind the brain drain in Togo’s health sector,” said Dr Monique Jameson- Dorkenoo, vice-president of the Togolese local and diaspora medical doctors association, which is known by its French initials, METODT. “Without these assets I do not think this phenomenon will stop,” she added.

About 40% of the qualified health staff trained at the capital’s University of Lomé leave Togo to seek better working and living conditions abroad, according to the WHO’s 2006 survey.

Dr Mawuagbé Koffi Siliadin, a health and development consultant, published a more recent survey in 2010 and limited it to the university’s 639 medical doctors (of the 695) who graduated during a 30-year period. The emigration rate nearly doubled from 40% in 1977 to 79% in 2007, he wrote in his study entitled “Togo’s Brain Drain”. The great majority of doctors who moved elsewhere are now probably residing in France, Togo’s former colonial master, according to his report.

This emigration hurts the country financially, according to Dr Siliadin. “This phenomenon causes important economic loss, about $16.8m in investment in training and $5.1m in annual loss to GDP and is a significant limitation to the capacity and development of our country.”

Most African general practice doctors migrate to France, Belgium, Germany, the United States and Canada, according to statistics published jointly by the WHO and World Bank in 2002. The same report revealed that many African health workers also move to other sub-Saharan African countries, primarily South Africa, but did not provide numbers.

At the Sylvanus Olympio Central University Hospital, Togo’s largest public health centre, sick patients sometimes spend agonising hours in waiting lounges before finally seeing a health worker.

“I had to wait for four hours before getting consulted and it is sad and deplorable,” said Evelyne Lawson, a 35-year-old tailor suffering from pneumonia. “I even heard that people sometimes die as a result of the service slowness due to the lack of staff. It is up to the government to ensure a good policy of medical staff recruitment because the right to health is universal.”

The few medical personnel who have stayed in Togo organised a union in April 2005, which is known by its French initials SYNPHOT. This year alone, the union’s 550 state-employed doctors and assistant doctors have staged three strikes calling for better housing, overtime pay, merit allowances and more liberal labour laws, among other demands.

Many Togolese human rights organisations have also joined this campaign to improve health workers’ recruitment and employment. They are calling for competitive wages and new minimum wage salaries, cuts in income taxes, more training and work placement for young doctors.

Poor working conditions and outdated equipment, combined with derisory salaries, are the main reasons behind Togo’s migratory flow of health workers, according to Dr Atchi Walla, the union’s coordinating manager.

The basic monthly salary of a Togolese medical doctor is 110,000 CFA francs or about $220, Dr Walla said. When you add the bonuses, a Togolese doctor earns 180,000 CFA francs a month or about $360. Their Benin counterparts earn nearly double, 350,000 CFA francs each month, about $700. But other professional salaries in Togo are low, too. A banker earns 200,000 CFA francs a month, about $400.

“Working conditions are very discouraging,” explained METODT’s Dr Jameson- Dorkenoo. “Despite the need for medical personnel, young Togolese graduates, even if they are bursting with patriotism, would not willingly come back given the current conditions, because most importantly, human beings should be able live from their earnings.”

Togo’s government is taking the country’s health crisis seriously and has tried to provide incentives to keep doctors and nurses in the country. Public servants in the health sector received a bonus of 100,000 CFA francs (about $200) in January 2009. The legislature adopted new civil service staff regulations at the end of 2012 and health workers will now benefit from a new insurance scheme as well as housing and family allowances.

During the last cabinet reshuffle in September 2013, the president attached the health ministry to the prime minister’s office so as to prioritise the health sector emergency. The health budget has increased from 29 billion CFA francs in 2011 ($61m, or 5.28% of the national budget) to 45 billion CFA francs ($90m, or 6.5%) this year, according to Togo’s health ministry. This still compares poorly to the average 15.5% OECD countries spent on health in 2011, according to the World Bank.

Much of Togo’s increased spending in the last three years has gone to upgrading

and re-equipping medical sites, including 50 walk-in medical clinics, 30 maternity wards and ten socio-medical centres, which provide basic healthcare services.

“According to the WHO standards, no Togolese should walk more than four kilometres to reach a health centre,” said Charles Kondi Agba, a former health minister. “It is for this reason that the Togolese government is buckling down and building new health centres. But I stress that without qualified medical personnel, these investments will not benefit the citizens.”

In July, the health ministry launched a recruitment drive for 986 doctors and nurses. Between May 2008 and October 2009, the health ministry recruited about 200 paramedical employees such as assistant nurses, assistant midwives and other health auxiliaries.

Despite these new initiatives, many Togolese doctors living abroad are reluctant to return, according to a survey published last year by the doctors’ association. Of the report’s 48 respondents (90% live in France), only 36% intend to go back to their homeland, according to the report. Limited professional growth, the lack of incentives to return and low salaries were the main reasons cited in the study.

Without qualified doctors or nurses or adequate facilities, Togo is unlikely to reach its MDGs related to health, which include reducing maternal and under-five mortality as well as combating HIV/AIDS, malaria and other diseases. According to its health ministry, Togo has reduced maternal mortality by 31%, miles below the three- quarters goal; under-five mortality by 14%, far below the two-thirds goal; deaths from malaria have decreased by 3% and new HIV infections by less than 10%.

Blame Ekoué is the Togo correspondent for the BBC and for Paris-based media house, ANA. He has also reported for Associated Press and Radio France International. He holds a BA in Communications from the Leader Institute in Lomé. Formerly deputy editor of the West Africa Revue, he has been a contributor to the Lome-based Business and Finance magazine since 2015.