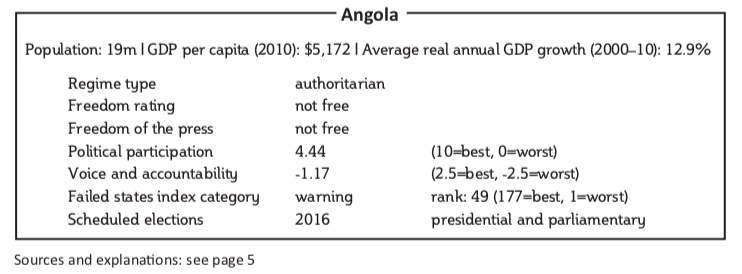

Angola’s new three-horse race.

by Louise Redvers

For four decades, two movements in Angola have battled it out, first in a 27- year civil war and then at the polls.

But now, the ruling Popular Movement for the Liberation of Angola (MPLA) and the National Union for the Total Independence of Angola (UNITA) have a new challenger: the Broad Convergence of Angolan Salvation (CASA-CE), mostly supported by voters who are too young to remember the civil war or who want a new voice in politics.

Abel Chivukuvuku, a one-time UNITA stalwart, who was close to its notorious late leader Jonas Savimbi, launched the new party in March 2012 after months of rumours and in time for the August 2012 polls. Mr Chivukuvuku, who lost a leadership contest against current UNITA leader Isaías Samakuva in 2003, hailed CASA-CE as a third way for Angolan politics and promised to bring something new to the table.

Mr Chivukuvuku drew a variety of respected public figures into his camp, including a retired navy admiral from a major MPLA family, a popular newspaper editor and several members of Angolan youth movements who had been staging anti- government demonstrations. With support mostly from young urban voters, the party managed to pick up eight seats in a parliament of 220, and pushed two other longer- established parties into fourth and fifth place.

While Angola’s oil revenues have raised its economic standing, very little of this money has trickled down into the hands of the majority. Half of the population live below the poverty line and many are without access to basic services like clean water, sanitation or electricity. For all the money poured into rebuilding Angola’s war- ravaged infrastructure, many roads remain unpaved, schools struggle to find teachers and hospitals are short on doctors, nurses and medication.

But the opposition parties in parliament won only 27% of the vote in the August elections and failed to capitalise on the high levels of discontent in the country.

Where is Angola’s opposition and why are they not winning more votes?

While several parties and civil society groups claimed that the 2012 election results were inaccurate and even fraudulent, the MPLA has an indomitable grip on the electorate. The MPLA’s share of the vote—72%, down from 82% in 2008—ensured that the party retained a two-thirds majority in parliament, allowing it to pass legislation as it wishes.

The MPLA assumed the role of government at independence in 1975. The competing liberation movements, UNITA and the National Front for the Liberation of Angola, fiercely disputed the MPLA’s legitimacy. Nearly three decades of civil war followed—at times a proxy cold war with intervention from the United States, Cuba, the Soviet Union and apartheid South Africa. The war ended abruptly in 2002 with the death of UNITA’s leader, Mr Savimbi.

The MPLA claimed a military victory and the credit for ending three decades of war. With the guns silenced, oil money and Chinese investment started to flow. New wealth granted the MPLA the means and the incentive to hold on to government and systematically entrench its members in every echelon of Angolan life.

The MPLA’s dominance stems from the complementary forces of “monopolistic politics” and “monopolistic economics”, said Inge Amundsen, writing in a paper for Norway’s Chr. Michelsen Institute. “The oil revenues make it easy to buy support … the benefits are substantial for those who adhere to and prove loyal to the party, but unavailable to those who are in opposition.”

The MPLA’s patronage network is pervasive, extending into the private sector, academia and the judiciary. Party loyalty is rewarded handsomely. Young people who do not join the MPLA’s youth wing struggle to qualify for study scholarships or simply fail to get into university. Those who are not members of local party committees face barriers to bank loans, promotion and even employment.

In recent years, most of the country’s private media have either been starved of advertising and folded, or bought by anonymously-held companies reportedly owned by senior government figures. In the rural areas, where the internet is rare, the only media readily available are government television, radio and newspapers. Government media are heavily pro-MPLA and rarely feature opposition or civil society figures except as objects of criticism or ridicule.

The MPLA’s control of the media and its lavish campaign spending create an environment in which opposition parties struggle to gain traction. The ruling party exploits Angola’s scarred past by portraying any challenge to itself or the government as an attempt to promote instability and re-start the war.

Despite leading an army at war for decades, Angola’s president, José Eduardo dos Santos, is known as the “architect of peace”. By contrast, Mr Savimbi is demonised. When there are complaints about the lack of development, references are often made to dams, bridges and other infrastructure which UNITA “blew up” during the conflict.

Both sides committed atrocities during the civil war. But in choosing an amnesty process, voted on unanimously in parliament in 2002, rather than a South African-style Truth and Reconciliation Commission, the details of Angola’s history have been buried and the ruling party’s hegemony has been strengthened.

“The MPLA has been very skilful in equating opposition politics and politicians with war,” explained Jon Schubert, a doctoral candidate at Edinburgh University, evaluating political authority in post-war Angola. “There is this whole stability discourse, where you have peace pitted against confusão (confusion), which in Angola is a symbolic code for war to which people are highly sensitive,” he said.

Many people make no secret of voting for the MPLA simply to avoid a repeat of the contested result of 1992 that triggered a new phase of the civil war.

Despite claiming that the latest results were fraudulent, UNITA decided to take up its seats in parliament, a move that has led the country’s youth to protest on the streets and accuse UNITA of hypocrisy. In its defense, UNITA says it will achieve more inside government than outside.

“We are determined to make our voices heard and what’s more, we are campaigning strongly to have parliamentary debates televised, so even if we lose all the votes, at least the public can better understand the issues at stake,” said UNITA parliamentary leader Raul Danda.

The UNITA of 2012 is stronger and more focused than the party that was so badly bruised in the 2008 poll. It doubled its share of parliamentary seats, from 16 to 32, and is more confident and outspoken.

Ironically, many believe Mr Chivukuvuku’s high-profile defection from within UNITA’s ranks was a much-needed jolt for leader Mr Samakuva and his executive team. “The emergence of CASA-CE really has dynamised the game,” Mr Schubert said. “It remains to be seen what happens in the next five years during this legislative period, but the appearance of [a] third party is a very interesting development and there is the potential for CASA-CE to become a real player in Angolan politics.”

In the weeks since the general election, Angola’s capital Luanda was besieged by power shortages, which also affected water supply. This was blamed on a drought, but the timing was awkward for the MPLA.

The spin doctors working for Mr dos Santos, in power since 1979, will be only too aware that with an estimated 50% of Angolans under the age of 18, future voters will have little of their parents’ battle scars or loyalties. They will be harder to win over if their needs are not met. Angola’s first local elections may take place in 2015. This new generation of voters may be the first serious challenge to decades of MPLA dominance.