Buried deep below Niger’s Sahel desert, uranium may change this West African country’s fortunes. Despite environmental fears, more and more nuclear plants throughout the world may be coming on line. Niger is capitalising on this growing demand, issuing more and more mining permits and hoping these radiating riches will lift it out of poverty. Richard Stupart looks at the scramble in the sand for nuclear fuel.

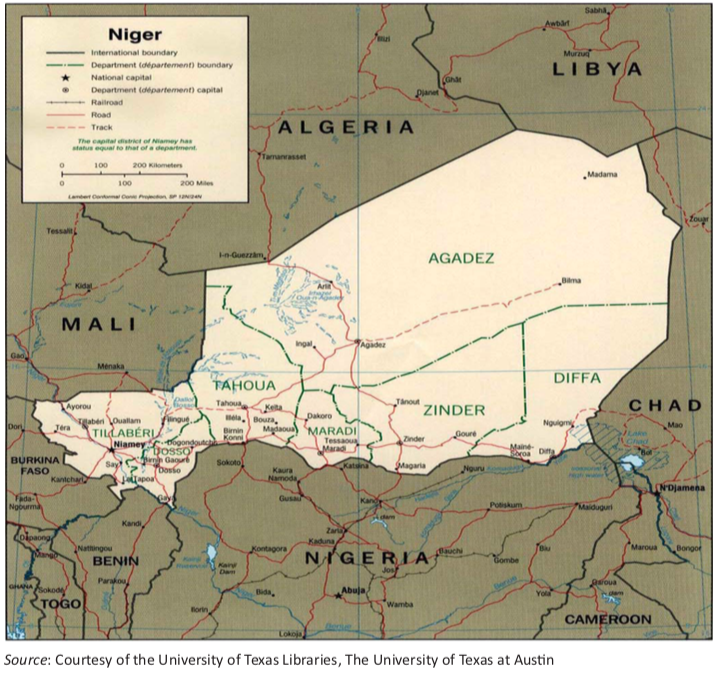

Niger is at an economic crossroads: its colonial history is colliding with the realpolitik of future energy security. Niger came under French rule in the 1890s and gained independence in 1960. During much of this time, this landlocked country’s largest export was groundnuts. Then in 1957, French geologists looking for copper stumbled upon uranium near the Aïr Mountains in Niger’s northern Agadez region. Fourteen years later, Niger’s first commercial uranium mine began operations. Arlit, the regional capital, quickly became the starting point for the “uranium highway” that led to neighbouring country Benin’s ports on the Atlantic Ocean.

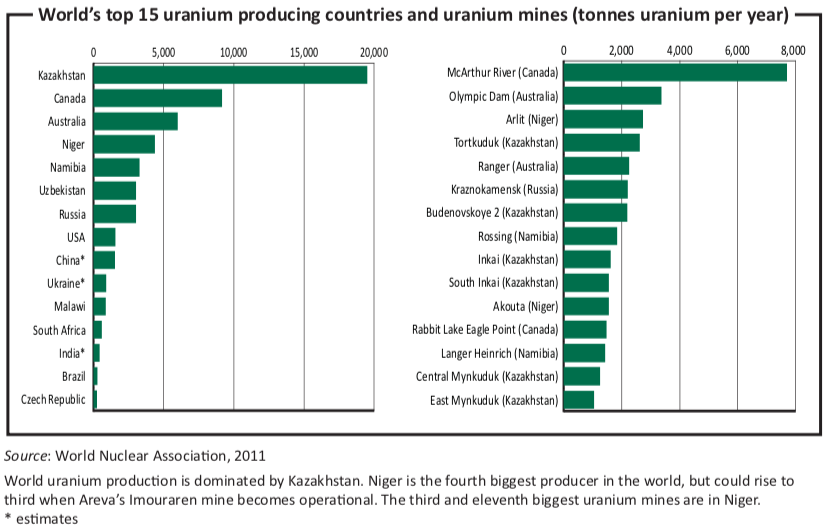

For decades, Areva, the state-controlled French utility company, jealously guarded this treasure. Thanks to Areva’s two mines in the region, Niger grew to become a leading exporter of uranium, fourth in world production following Kazakhstan, Canada and Australia. Though uranium annihilated groundnuts as Niger’s primary export, the price of the radioactive metal hovered under $20 per pound and failed to power the country’s growth and development.

Considered one of the world’s least-developed nations, Niger has languished at the bottom of the human development rankings for years, only a notch above the Democratic Republic of Congo, according to the United Nations Development Programme. The average Nigerien lives 54 years and is likely to be illiterate. He is likely to be sick and hungry as the country’s health system is basic and malnutrition and disease, particularly malaria and tuberculosis, are widespread, according to the World Health Organisation. The country has endured repeated famines and its politics, hit by a Tuareg insurgency in 2007 and then a coup in 2010, is unstable. Per capita income has actually declined by about 30% since 1980, according to the World Bank.

This state of affairs suited France for many years as Areva monopolised the mines and continued digging deeper into the Agadez desert. The former colonial power is dependent on fission for more than 75% of its national power output—the highest dependency in the world. Its two subsidiaries extracted 10% of the world’s uranium in 2005 which accounted for 30% of France’s consumption that year. When Areva’s planned Imouraren mine comes online in 2014, it is expected to produce an additional 5,000 to 7,000 tonnes of the mineral per year. This extra yield would more than double Niger’s 2011 output of 4,198 tonnes and move it into third place behind Canada (9,783 tonnes) and Kazakhstan (17,803 tonnes).

France’s monopoly of Niger’s uranium production is about to be overturned as other countries abandon fossil fuel and show more interest in nuclear power. Even Japan, wavering after the March 2011 disaster at the Fukushima Dai-ichi nuclear power plant, looks set to fall back on nuclear energy once more. China has plans to bring up to another 120 reactors online in the coming years. World nuclear energy production is expected to surge from the 433 nuclear reactors operating today to 985 by 2030, according to the World Nuclear Association, a London-based nuclear energy lobbying group. Even after adjusting for the 60 to 156 reactors that may shut down during this period, the picture is one of enthusiastic growth.

To supply these current and future nuclear plants, the Niger government has been issuing many more permits that were once reserved for Areva. The China Nuclear International Uranium Corporation is developing the Abokorum deposit in Agadez. Other countries scrambling in the sand include Japan’s Toshiba Corporation, Australia’s Artemis Resources, Russia’s GazpromBank NGS, India’s Earthstone Group and Taurian Resources Pvt Ltd, and Canada’s Homeland Uranium.

As more companies vie for this metal, its price has begun to look like the heartbeat of an excited prospector. After hitting a nadir of $7 per pound in 2001, lagging production and enthusiastic demand led to an inadequate global supply and uranium skyrocketed in 2007 to $137 per pound, according to the United States Environmental Protection Agency.

The market has settled and now stands at around $50 per pound. This price may rise again as another shortfall is predicted if Russia does not renew its “megatons to megawatts” agreement, as expected. Under the agreement, Russia removed uranium from warheads from its cold-war stockpiles and sold it to American and European reactors. This programme was responsible for supplying about 15% of world demand.

Niger’s Imouraren facility may supply this global demand for uranium and provide additional revenue for the Nigerien government. An International Monetary Fund report projects Niger’s uranium exports to triple from 3,500 tonnes in 2011 to 10,500 tonnes in 2016.

For the most part, Niger’s uranium riches have left the country, leaving behind contaminated waste. When the wind blows, powder from a massive hill containing 35m tonnes of radioactive waste just outside Arlit, scatters over the town, according to German publication Der Spiegel. An April 2010 European parliament report found deaths due to respiratory infection in Arlit to be twice the national average—while radon, a by-product of uranium decay, seeped into the water table. In the streets of the nearby mining town of Akokan, Greenpeace investigators measured levels of radiation 500 times higher than normal.

In response to criticism from environmental groups about its treatment of Nigerien workers, in 2009 Areva finally provided a medical facility where employees may be screened for radiation, a long-awaited move towards properly dealing with the radiation damage that Areva’s facilities may have caused.

If the future of uranium is as bright as the evidence suggests, then Niger may have a rare opportunity to share its fortunes with its citizens and improve their lives.