During the 2001–2008 commodities boom, South Africa’s mining sector shrank by 1% a year, while the world’s top 20 mining countries achieved an average growth rate of 5% a year, according to South Africa’s Chamber of Mines. Much of this decline is due to a dramatic drop in gold production, which has halved in the last 10 years. But policy uncertainty, regulations and infrastructure are also to blame. J. Brooks Spector examines how South Africa fell off the commodities cliff.

South Africa’s extraordinary mineral wealth has been the core of its economy since 1867, when diamonds were discovered on a farm near Kimberley in the country’s Northern Cape province. Almost 20 years later, huge gold deposits were unearthed near Johannesburg and South Africa became one of the world’s paramount mining countries. Today it houses the world’s largest reserves of chromium, gold, manganese, platinum and vanadium.

Despite this trove of natural resources, South Africa has missed the commodities boom, mostly fuelled by China’s extraordinary economic and industrial growth. Instead, an uncertain investment climate due mostly to calls for nationalisation, ageing infrastructure and mines, and burdensome regulations have led to a contraction in the mining sector.

The commodities boom coincided with the overhaul of South Africa’s mineral rights regulation, says mining law specialist Peter Leon. The Mineral and Petroleum Resources Development Act of 2002 replaced private ownership of mineral rights with state custodianship and conditional mining licenses supervised by the department of mineral resources. This new system led to long delays in processing mining licenses and deterred potential investment. In contrast, other countries such as Mozambique adopted investor-friendly codes and thereby attracted new exploration and production.

Calls for nationalising South Africa’s mines remain a contested topic in this country and are blamed for its shrinking mining sector. Proponents argue it is the way to liberate wealth that has been extracted—then effectively stolen—by the country’s mining houses. Opponents argue that continuing advocacy of such policies has created an unstable investment climate and depressed domestic and foreign investment in the mining sector.

“The nationalisation debate put a damper on mining investment,” says a foreign diplomat familiar with the mining sector. “And infrastructure deficits in rail, ports and energy have also discouraged mining investment. The bottom line: the government has grand visions of building new manufacturing industries, but it has done a lousy job of supporting mining, even though it remains one of South Africa’s biggest employers and sources of export earnings.”

The mining sector accounts for nearly 9% of South Africa’s gross domestic product (GDP) and more than one-half of export earnings, according to a Chamber of Mines executive. It employs half a million people.

The diplomat blames history for the government’s ineptitude. Gold and other minerals created the foundation for South Africa to become the continent’s largest and most advanced economy. But many still recall the apartheid era when a black workforce extracted this wealth for the benefit of white-owned companies.

“The ANC [African National Congress] seems to have a deep ambivalence about mining, probably because of the sector’s role in structuring the apartheid economy,” he says. Until now, the ANC has devoted more thought and energy to “transforming” the mining sector than to nurturing it and ensuring that it drives growth for decades to come, he adds.

Crumbling and inefficient infrastructure has also undermined South Africa’s mining potential. The growing deficiencies in transportation and railway capacity for bulk commodities began driving up mining costs from about 2000 onwards, says economist Mike Schüssler.

For instance, the state-run Transnet Rail service hauls coal for export to Richards Bay on South Africa’s east coast. Though the port’s annual export capacity exceeds 91m tonnes, the rail network could move only 68m tonnes last year. Electricity prices have nearly doubled in the last few years and the entire country has suffered from frequent power outages since 2007.

Costs and insecurities have continued to mount from this period onward, Mr Schüssler says. First there were potential social security expenses and then a proposed national health care plan. Then charges that energy and chemicals company Sasol had been extracting “super profits” from its synthetic petroleum production fuelled the nationalisation debate, he adds.

The need to invest in greater beneficiation, or complementary industries that raise the value of the raw natural resources, was added to this simmering cauldron, Mr Schüssler says. From the industry perspective, this meant extra costs added to already burdensome affirmative action requirements.

These additional expenses and red tape depressed investment in the mining sector, says economics journalist Barry Wood. “Overall South Africa is not seen as particularly hospitable to FDI [foreign direct investment],” he says. He is reluctant, however, to admit that South Africa has entirely missed the commodities boom. “Without coal, gold and platinum exports, forex [foreign exchange] earnings would be tiny,” Mr Wood says.

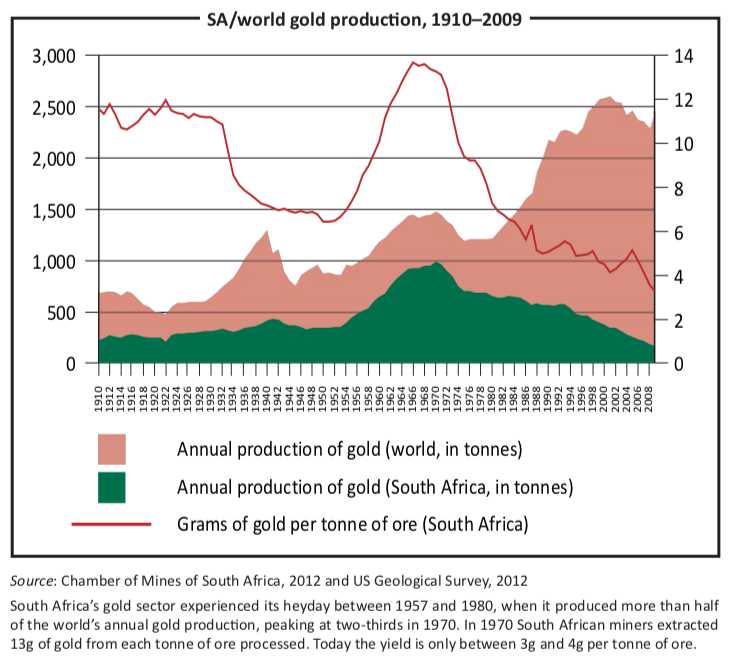

Gold is also a major factor in South Africa’s shrinking mining sector. Its ageing gold mines are getting deeper and thereby dearer to explore. From 2000 to 2010, annual gold production dropped from 428 tonnes to 191 tonnes.

There is yet another issue beyond South Africa’s borders: China. South Africa has suffered from “a significant lack of understanding of the significant developments in the Chinese economy and the actual drivers of commodity demand in that country,” says China–Africa trade specialist Martyn Davies.

It may be too late to learn for China’s economic engine and its consequent demand for raw materials are slowing down, even if the country still has growth rates most nations envy. China consumes half of the world’s annual iron ore production and more than a third of most base metals, says Edward Russell-Walling in The Wall Street Journal. But “China is unlikely to trigger a full-scale commodities rescue in the near future,” he says. This cannot be a cheering prospect for a nation hoping China’s demand for minerals will be the overwhelming driver for domestic mining expansion.

But if South Africa has failed to benefit fully from the recent boom, how should it prepare itself for the next positive economic cycle? South Africans debate beneficiation from mining in too limited a sense, concentrating on jewellery manufacturing instead of broader industrial plans, says economist Iraj Abedian. Where is South Africa’s research and development on chrome and magnesium, he asks, given its generous endowment of these metals.

The crucial problem is the government’s questionable planning skills. South Africa “needs a capable state that can plan in an integrated manner across state institutions as well as parastatals”, Mr Abedian says. Absent such a change, South Africa “could end up in a [new] version of the colonial past. We’ll dig, then battle over taxation, have energy shortages. In short, it will be the opposite of leveraging upward.”