Historically, the emergence of large middle classes is a recent phenomenon. Africa is late to the party and Richard Stupart argues it may be too soon to break out the champagne.

Africa is a continent often maligned for the huge divide between its miserable poor and bloated rich, but its emerging middle class is now the subject of optimistic chatter.

Several reports on the middle class in Africa paint a picture of an African golden age full of possibilities for driving growth through middle-class consumption. They have unleashed a Pollyannaish glee among corporates who are salivating over the opportunity of selling to more than 300m middle-class Africans they had not noticed before.

But are there 300m middle-class Africans? It all depends on how you define the middle class. The McKinsey Global Institute, a consulting firm, defines middle-class households as those with incomes of $20,000 per year or more, and says Africa’s middle class outstrips India’s.

The African Development Bank (AfDB) definition is much broader and says Africa’s middle class ranges from earning $520 per year to $5,200 (or $2–$20 per day.) Unlike McKinsey, it ranks those earning more than $20,000 a year as rich.

Both reports say Africa is joining the world’s consumers of dishwashers, refrigerators and automobiles. The AfDB report, while more optimistic, is also more comprehensive. It raises important questions about defining the African middle class and its broader implications for the future of the continent.

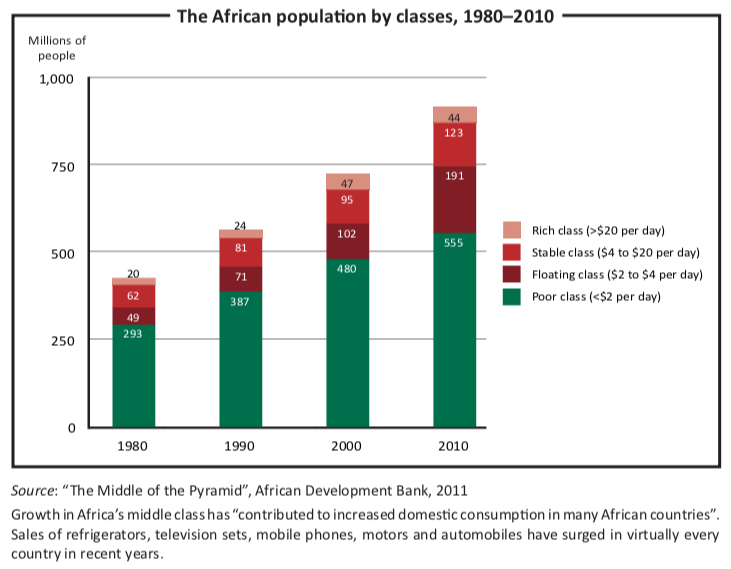

The AfDB report claims that the size of the African middle class, those earning between $2 to $20 per day, nearly tripled to 313m people in 2010, or 34.3% of the continent’s population. This is up from the 26% measured in 1980 and the almost unchanged 27% measured in 1990 and 2000. At first blush, the continent has moved from stagnation in individual prosperity before 2000 to impressive gains in the numbers of those with middle-class levels of income.

Except that the AfDB middle class of these projections is not the same as the anecdotal middle class that purchases dishwashers and weekend holidays. The AfDB category is an amalgamation of a “floating middle class” whose daily consumption levels range from $2 to $4 a day and a stable middle class whose consumption levels lie between $4 and $20 a day. This is a very broad definition and not a conventional middle class.

At a maximum of four dollars a day, you are unlikely to participate in higher education, live in the suburbs or fulfil the same political and economic role in the life of a nation that the middle classes of the developed countries do. Put simply, members of this floating middle class are different politically and economically from their wealthier colleagues.

What about removing the floating middle class ($2 to $4 a day) from the equation and examining instead the gains made by combining the stable $4 to $20 class? Have they grown?

There’s the rub. When comparing the proportions of this stable $4 to $20 middle class not much has changed. Although it has nearly doubled from 62m in 1980 to 123m in 2010, its share of the continent’s population has decreased slightly from 14.6% in 1980 to 13.4% in 2010.

“In terms of absolute numbers, both the stable and floating middle classes have been increasing over time but not at the same rate—with the floating class in particular enjoying much more robust growth,” says Maurice Mubila, AfDB head statistician. “However, in terms of proportions, the stable middle class [$4 to $20] appears to have shrunk a bit while the proportion of the floating class has increased.”

Earning a maximum of $4 a day, this floating middle class has little disposable income to spend and is unlikely to be capable of fulfilling the middle-class promise of economic and political stability.

Those paddling in the floating $2 to $4 category are almost rich enough to join the stable middle class, but remain vulnerable to external food and fuel price spikes, inflation and the spectre of sliding back to sub-$2 levels of poverty. Their share of the population has increased from 14.7% in 2000 to 20.9% in 2010, according to the AfDB.

They comprise about 200m of the AfDB’s misleading middle-class definition and the implications of their growth are profound. They remain barely above the poverty line and have trouble making the transition into the more stable middle-class category of $4 to $20 a day. In Africa’s three most populous countries, Nigeria, Ethiopia and Egypt, more than half the middle class is in the floating category, living on less than $4 a day.

This floating middle class matters because of its potential to act as either a disruptive or a stabilising force. As urbanisation on the continent continues (McKinsey estimates that around 40% of the population now live in cities), these city-based populations could become a stronger source of political pressure on many governments unused to dealing with mass popular movements.

Potentially, as this floating class rises to a more secure economic position, it will begin to assume the more progressive political stance associated with a middle class: one that demands accountable governments that uphold the rule of law, protect property rights and provide public services, according to the AfDB report.

In nations with authoritarian regimes, such as Rwanda and Uganda, it is unclear how these demands will square with governments unwilling or unused to seeing political and economic power shifting away from the state. In more democratic countries such as Kenya or South Africa, a larger, true middle class may serve to cement those values and act as a counterweight to authoritarian politics.

Just as the floating class may migrate upwards towards becoming a more traditional middle class, so too might it fall back below the $2 a day line in the face of sudden shocks like rises in food and fuel prices, which this group cannot absorb as easily as the richer classes are able to do.

The floating middle class amounts to more than a third of the population in 19 different countries (a fifth in 26 countries) and the results of its reactions to these pressures can be potentially devastating to the state. The mass mobilisations in Nigeria in January 2012 that brought Lagos to a standstill over the withdrawal of the fuel subsidy, Uganda’s walk-to-work protests in April 2011 and the rioting in Mozambique in September 2010 over an increase in the price of bread are all warnings of just how volatile an urban floating middle class can be when such shocks occur.

An explosion in the size of the African middle class—as the AfDB and consumer goods manufacturers of all stripes argue—would be an economic driver for further growth led by domestic consumption and a force for generally more accountable politics.

But the truth is that it has not happened. What has grown is the AfDB’s misnamed urban floating middle class. The political and economic future of many countries will be linked inextricably to this new group. It is not the 13% that are truly middle class that should be watched. It is the 20% teetering on the very edge of joining them.