Democratic Republic of Congo: M23 rebels surrender

A three-pronged approach to end the cycle of violence in DRC

Lessons can be drawn from the recent surrender of the M23 rebel group in the eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC). The group finally ended its 18-month struggle last November 5th because it was confronted by a better-organised and trained national army, beefed-up United Nations support with a mandate to attack, and international pressure on the group’s supporters, Rwanda in particular, to stop aiding the group.

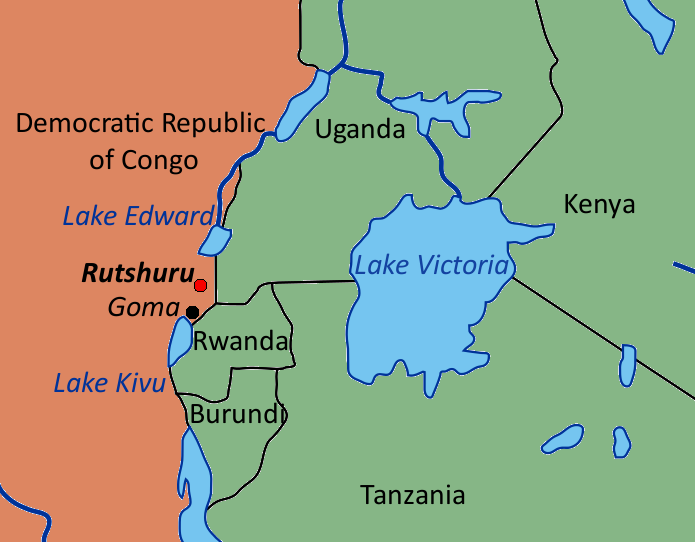

For two decades the eastern DRC has been a region of intractable conflict and weak state presence. Civil unrest and war have distorted local economies, displaced populations, fuelled grievances and inflicted much suffering. While the M23 and the government are holding peace talks in Kampala, Uganda, dozens of other armed militias remain and are wreaking havoc in the region.

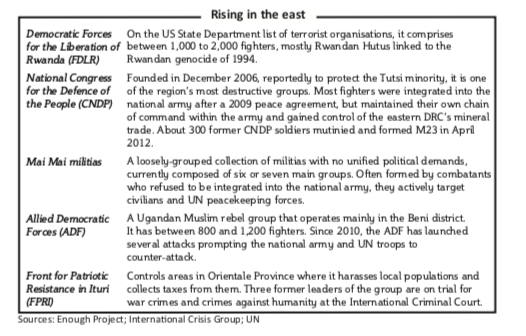

The alphabet soup of acronyms is hard to master and at least 28 armed militias are active in the eastern DRC, according to the Enough Project, a US-based advocacy group. They range from rag-tag self-protection groups of a dozen men armed with machetes and hunting rifles to trained, disciplined armies of thousands (The Democratic Forces for the Liberation of Rwanda or FDLRmay comprise at least 2,000 combatants, according to UN figures.) Some are fighting for ideology, others for ethnic reasons or for financial gain, and, for many, after so much time, it has simply become a way of life.

To make a dent in breaking the remaining rebel groups it helps to understand the M23’s origins. The M23 had its roots in the National Congress for the Defence of the People (known by its French initials, CNDP), a Rwanda-backed Tutsi rebellion. An accord signed on March 23rd 2009 called for the group’ integration into the national army, which it claims was not respected. When it broke away, it used this date to name itself, hence M23. The M23 cited other grievances including a lack of political representation, ethnic and linguistic divisions, and joblessness, gripes that many in the eastern DRC share.

The M23 had long claimed that the DRC’s president, Joseph Kabila, was lacking a popular mandate because the 2011 elections were marred by corruption and violence, an assertion backed by the Carter Center, which observed the polls. Many in the DRC share the M23’s feelings of alienation from the central government xxmiles away in Kinshasa. Bertrand Bisimwa, the M23’s political president, denounced the government in Kinshasa last August for its “negative governance that kills its people, that rapes its citizens”.

Like its Rwandan-backed predecessor, the CNDP, the M23 claimed that the interests of the minority Tutsi ethnicity and Kinyarwanda-speaking communities are not represented in the DRC. Since the mid-19th century, Rwandans—many Tutsis—have emigrated into the Congo, with the largest wave arriving during the 1994 genocide in Rwanda in which 800,000 Tutsis and moderate Hutus were murdered in about three months. Each surge has caused disruption to local communities.

To add to the ethnic tension, linguistic divisions fuel discrimination in the Congo. Kinyarwanda is spoken in Rwanda, but also by the descendants of Rwandans who emigrated many years ago into the neighbouring Congo. Kinyarwanda-speaking children whose great-great-grandparents came to what is now the DRC from Rwanda over 130 years ago are still not considered to be Congolese.

Lack of economic opportunity in a country with vast natural resources remains a major reason behind the formation of dissident groups in the DRC. The well-worn narrative claims that the rebels lived off rents from gold, copper, diamonds, tungsten, coltan and other precious metals and minerals used in mobile phones and computers. While this is partly true, the M23 derived much of their income through extortion. They controlled the approximate 100km route that winds north from the commercial capital of Goma towards the shores of Lake Edward and collected about $300 from each truck driver. In addition, they demanded 3,000 Congolese francs (about $3) per quarter from each shop owner and 1,000 Congolese francs per month from each family in the areas they controlled.

The M23 lasted 18 months because the DRC is a notorious failed state and did not present much of a military or political challenge. But a committed offensive by the Congolese national army (FARDC) in late October defeated the M23 within 11 days. It was a display of the army’s new discipline and strength. The army has now been streamlined with regional commander, Generl Lucien Bahuma, and the operational commander, Colonel Mamadouo Ndala prioritising logistics and ensuring that the national army has been paid regularly, according to Jason Stearns, an expert on the DRC. Kinshasa recalled under-performing or corrupt national army commanders and replaced them with motivated tacticians.

The UN’s military support also played a major part in defeating the M23 and may be relied upon to outgun other rebel groups. Its new intervention brigade, armed with an assertive mandate, deployed attack helicopters and artillery against the M23. Their reputation as well-armed, well-trained soldiers may already be encouraging other rebel groups to surrender. Ntabo Ntaberi Sheka, leader of one of the most violent Mai Mai militias in the eastern Congo, announced last November 5th that he is ready to lay down arms if granted amnesty, according to Fidel Bafilemba, a researcher with the Enough Project.

Last but not least, Rwanda and Uganda, to a lesser extent, have played a significant role in supporting the M23 rebellion. But international pressure led the US to withdraw about $200,000 in military aid to Rwanda, according to the US State Department.

This successful three-pronged approach—a strong national army, backed with UN troops and international pressure on rebel supporters—might show promise against other rebel groups. However, most rebel groups in the DRC are not as easily accessible or as centralised as the M23. This presents a problem for the national army and the UN troops. In addition, few of the remaining rebel groups have direct foreign backing, so international pressure may not be an option.

The FARDC and the UN will probably next pursue the FDLR, according to the Enough Project. This Hutu militia, formed by perpetrators of the 1994 genocide who fled Rwanda, makes occasional sorties into Rwanda. Rwanda considers them a security threat and for this reason backed the mostly-Tutsi M23.

Unlike the M23 that was centralised in Rutshuru, the FDLR has two command structures, one in North and the other in South Kivu. It operates in densely forested areas with only one good road, which runs from Goma through Rutshuru, making access to their camps very difficult.

The three-pronged approach has succeeded in bringing the M23 to peace talks. Ensuring they do not re-emerge is another challenge. Rebel groups’ grievances must be addressed. These include their demands for political participation and economic opportunity. The government in Kinshasa desperately needs to create accountable institutions to control and unify this huge country. The M23’s defeat is a specific story and future battles will each have their own dynamics, but there is space for cautious optimism.

[author] [author_image timthumb=’on’][/author_image] [author_info]Joseph Kay is a freelance journalist who has been based in Goma, DRC, since June 2013. Joseph has a degree in Philosophy and spent three years working with NGOS managing development and emergency projects in DRC between 2009 and 2012.[/author_info] [/author]