Mozambique’s Renamo

From rebel group to political party and back again: Renamo’s recidivism defies the sunny prognostications of the “Africa Rising” narrative

by Richard Poplak

For decades, it seemed as if the Mozambican civil war, which raged from 1977 to 1992, was resolutely over. While the ruling Front for the Liberation of Mozambique (Frelimo) enjoyed a lock on power, its arch-rival, the Mozambican National Resistance (Renamo), was not disbanded in bloody recrimination following defeat. Rather, Renamo has enjoyed official opposition status in Maputo, many thousands of kilometres from its Gorongosa game park stronghold in the country’s distant hinterland.

Recently, however, the group has scraped away the veneer of legitimacy and found its rebel army roots, facing down the government on a host of issues, most notably electoral reform and the uneven distribution of the spoils from a resources boom. From rebel group to political party and back again, Renamo is an example of the recidivism that the newfound “Africa Rising” narrative finds difficult to incorporate into its sunny prognostications.

The situation hit its inevitable nadir on October 21st 2013: following an army raid on their base, Renamo pulled out of the 1992 Rome General Peace Accords that marked the end of a civil war that killed a reported million people. While Renamo forces staged a retaliatory attack on a police station in the central town of Meringue, none of its 51 representatives resigned from the unicameral Assembly of the Republic—a case of mixed messages if ever there was. No one was killed in the station raid, but it nonetheless ignited fears that Mozambique, currently boasting one of the fastest growing economies in the world, would slip back into conflict, undoing a steady decade’s worth of near seven percent GDP growth.

Of all southern Africa’s liberation-era movements, Renamo’s history may be the most compromised. Famously, it is the son of Ian Smith’s white supremacist Rhodesian regime. When Mozambique declared independence from Portugal in 1975, Mr Smith understood that communist Frelimo presented an existential threat to his tentative hold on power. The new country had become a haven for Zimbabwe African National Union (Zanu) forces. As a countermeasure, Rhodesia’s notorious Central Intelligence Organisation sponsored an ex-Frelimo commander, named André Matsangaissa, in a nominal anti-communist campaign against his former party. The United States’ Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) cheered on from the sidelines.

A 1989 research report titled “The Mozambican National Resistance (Renamo) as Described by Ex-participants” written by a Georgetown University doctoral graduate named William Minter, summed up the group’s thorny etymology, and thus its place in the larger Mozambican cultural continuum:

“The Resistência Nacional Moçambicana (Mozambican National Resistance [or MNR]) is the name used by the organization itself. The Portuguese-language acronym Renamo was adopted by the organization in 1983, and is now more widely used than the English-language acronym MNR. The Mozambican government and Mozambicans when speaking Portuguese, generally refer to the group as ‘bandidos armados’ (armed bandits), ‘bandidos,’ or, sometimes, ‘bandos armados’ (armed bands). This is often abbreviated in popular speech to “BA’s.” The most common term used in local languages, and often in Portuguese as well, is ‘matsangas,’ after the first Renamo commander, André Matsangaiza [sic].”

Mr Minter describes a group that press-ganged young men into service, and one that ran less on single-minded anti-communism and more on floggings and solitary confinement. Nonetheless, Ian Smith’s mélange of ideological outrage and expediency was picked up by South Africa’s apartheid regime after Zimbabwe emerged from the wreckage of the bush war in 1980. Mozambique became an exilic hotspot for members of the African National Congress (ANC) in their fight against white rule, and Pretoria kept stoking a full-blown conflagration. The signing of the Nkomati Accord in 1984 was meant to stem the regime’s support for Renamo in exchange for the expulsion of all ANC members from Mozambique. Frelimo balked, however, and it was eight long years before the Rome Accords paved the way for peace. By 1994, Renamo’s leader Afonso Dhlakama had flipped the switch from rebel group to political party, and in 2004 he won over 30% of the popular vote.

This was not the happy ending it initially appeared to be. In October 2012 Mr Dhlakama, along with 800 erstwhile members of his guerrilla force, returned to Gorongosa from his northern redoubt in Nampula province, because his men there “were feeling ignored”, as he put it. In many respects, this manoeuvre was made out of longstanding exasperation: Frelimo holds 191 of 250 seats in parliament, and Renamo has long claimed that they were won fraudulently. With elections looming in 2014, Renamo wanted political parties granted more oversight of the National Electoral Commission (CNE), which was designed to be more of an independently minded, civil society-motivated institution. That said, Renamo claims that the commission is guided by Frelimo’s heavy hand. But according to the law, parties with more representatives in parliament are granted more seats on the CNE. Renamo threatened to skip municipal elections on November 20th 2013 and federal elections on October 20th 2014, should their demands be ignored.

In April 2012, when relations between Frelimo and Renamo were at their lowest ebb in decades, Renamo sent a letter to the Mozambican cabinet, bemoaning that it has been denied the windfall produced by Mozambique’s natural bounty. The letter was not a policy document, but rather a demand for Frelimo to explain “why [Renamo] remains excluded from enjoying the wealth which resulted from the peace it helped to achieve and maintain during the past 20 years”. It is still unclear precisely what Mr Dhlakama and company were asking for, but the party did make the point that more “access to wealth” would allow the remaining rebels in central Mozambique to be properly transitioned into the national armed forces—a claim that the government disputes.

In one important aspect, Renamo’s grievances are very clear: Mozambique, like Canada, partially funds political parties based on representation in parliament. Renamo has bled badly due to an intra-party split that saw the formation of the Mozambique Democratic Movement (MDM), which won eight seats in the 2009 legislative elections and saw Renamo lose 39 of the 90 seats that it had previously held. With funding from the government slashed almost in half, Renamo has felt increasingly marginalised, and this has certainly motivated the move back into central Mozambique, and the sense of déjà-vu that has pervaded events over the course of 2013. On April 4th, the government hit Renamo headquarters in Muxúnguè, central Mozambique, to disrupt and disperse Renamo forces performing military manoeuvres. Swiftly thereafter, the bloodshed began in earnest, when Renamo attacked the police base in which its members were being detained. Four were killed and eight injured.

The international community started paying attention in June, when Renamo established a blockade on a key road in the country’s middle belt and threatened to block rail cars with bellyfuls of coal from reaching the port in Beira. This spooked international investors and inspired Markus Weimer, an analyst at Control Risks Group, a consultancy, to tell CNBC Africa that “the impact of this situation is much greater when it comes to the reputation of Mozambique as a business destination. This sort of thing raises doubts in investors’ minds whether this is the right country to invest in. I believe that it is the right country to invest in—it will be overcome, it can be overcome—but investors who look at this case really and thoroughly might be put off by this”. (In early November, London-based mining company Rio Tinto said it was withdrawing expatriate employees’ families from Mozambique for their safety in response to the upsurge in kidnappings and violence, according to Reuters.)

This, no doubt, is part of Renamo’s intention. And it leaves President Armando Guebuza’s administration straddling a difficult line. On the one hand, it has committed the army to breaking blockades and military activities in the north. On the other, it has made conciliatory noises to Renamo parliamentarians in Maputo. Mr Dhlakama will not negotiate face to face, because he says that he fears for his safety. And without the tether of the Rome Accords, there is nothing currently binding the two enemies from returning to a state of open conflict.

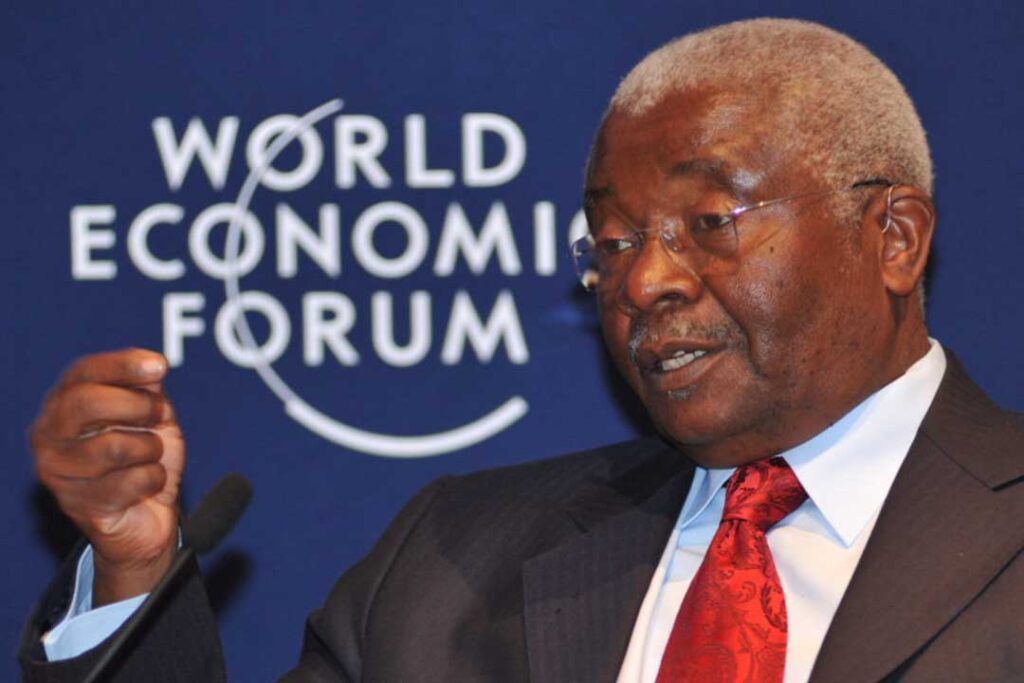

Copyright (cc-by-sa) © World Economic Forum (www.weforum.org/Photo Eric Miller [email protected]

It might also be said that the era of a southern African country descending into out and out civil warfare is perhaps behind us. Zimbabwe has no desire to see the conflict resume, nor does South Africa. No longer functioning as a proxy to outside players, Renamo finds its war chest far barer than it did 20 years ago. While it certainly could recruit based on the anger many Mozambicans carry regarding Maputo tardiness in raising basic living standards,recruiting an army of 20,000 seems virtually impossible. But a status quo involving small skirmishes, railroad ambushes and disrupted coal shipments is in not in the country’s best interests.

“Peace is over in the country,” Renamo spokesman Fernando Mazanga told Reuters. “The responsibility lies with the Frelimo government because they didn’t want to listen to Renamo’s grievances.”

Whether or not Frelimo starts listening is based on how seriously it takes the threat to Mozambique’s stability as an investment destination. It is a bitter irony: just as the country was taking flight, old ghosts have emerged from the killing fields of the civil war. The ruling party will need to appease Renamo without appearing to buckle to their tactics, a virtually impossible task. Mozambicans desperately need them to find that balance if the country hopes to grow and flourish.