Funding health and development

A new finance plan hopes to improve incentives and accountability in aid projects

by Ivo Vegter

Critics often condemn development aid for being ineffective and wasteful. A new breed of funding models—social impact bonds and development impact bonds— seeks to remedy these failings by providing incentives to funders, donors and aid recipients.

To see how these models differ from existing practice, we need to review development financing and its shortcomings. Two main funding models exist.

In the first, investors lend government money with the expectation that this money is returned with interest in the future. This is a classic bond: governments take on debt to fund major projects in healthcare, education or infrastructure.

In the second model, donors give money to the same governments or directly to non-profit implementation agencies, with the expectation that no money is returned in the future. This is the classic foreign aid model.

Jody Kusek and Ray Rist, authors of a book published by the World Bank entitled “Ten Steps to a Results-Based Monitoring and Evaluation System”, observe that there is growing pressure on governments and organisations around the world to be more responsive to the demands of citizens, donors and other participants. They note that outputs and outcomes are not the same. Completing a healthcare project may imply successful implementation, but has it improved public health as intended?

Despite well-developed bureaucratic planning, the results of aid spending in the last half-century make for depressing reading. “The West spent $2.3 trillion on foreign aid over the last five decades and still had not managed to get twelve-cent medicines to children to prevent half of all malaria deaths,” laments William Easterly, a professor of economics at New York University in his book on the failure of development aid, entitled “The White Man’s Burden”. “The West spent $2.3 trillion and still had not managed to get four-dollar bed nets to poor families. In a single day, the American and British economies delivered 9m copies of the sixth volume of the Harry Potter children’s book series to eager fans. It is heartbreaking that global society has evolved a highly efficient way to get entertainment to rich adults and children, while it can’t get twelve- cent medicines to dying poor children.”

Two competing theories about development aid have emerged, according to Claudia Williamson, an assistant professor of economics at Mississippi State University. The first reflects the status quo, epitomised by the writing of economist Jeffrey Sachs, which argues that aid fills a financing gap that will lift countries out of a so-called poverty trap. A contrasting theory, a public choice perspective, contends that foreign aid is ineffective and possibly damaging to recipient countries.

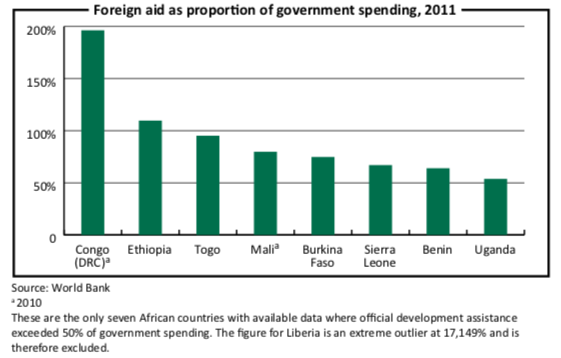

Mr Easterly is of the latter school of thought. So is Angus Deaton, professor of economics and international affairs at Princeton University. He explains the harm in a recent article for Project Syndicate: “Unfortunately, the world’s rich countries currently are making things worse. Foreign aid—transfers from rich countries to poor countries— has much to its credit, particularly in terms of healthcare, with many people alive today who would otherwise be dead. But foreign aid also undermines the development of local state capacity. This is most obvious in countries—mostly in Africa—where the government receives aid directly and aid flows are large relative to fiscal expenditure (often more than half the total). Such governments need no contract with their citizens, no parliament and no tax collection system. If they are accountable to anyone, it is to the donors; but even this fails in practice, because the donors, under pressure from their own citizens (who rightly want to help the poor), need to disburse money just as much as poor-country governments need to receive it, if not more so.”

Corruption compounds this cocktail of failure, argues Dambisa Moyo in her book, “Dead Aid: Why Aid Is Not Working and How There Is a Better Way for Africa”. The problem is that funders have no direct incentive to hold the implementing agency accountable, whether the grant consists of a loan with guaranteed repayment or a donation with guaranteed non-repayment. It makes no financial difference to them whether a project fails or succeeds.

The lack of incentives goes to the heart of the crisis in aid delivery, Ms Williamson argues in a July 2009 paper published in the Review of Austrian Economics. “We should not be surprised that foreign aid does not actually achieve its intended results,” she writes. “Governments and aid agencies are simply incapable of creating either the incentives or the information necessary to achieve development.”

Fortunately, a different approach exists that “achieves development through aligning the right incentives”, she adds. “Instead of relying on collectivist mechanisms, we could turn to private, decentralised actors operating in the market to achieve marginal successes.”

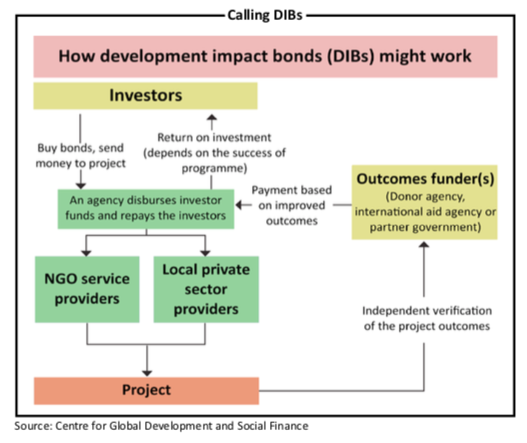

This is the context in which first social impact bonds (SIBs), and more recently, development impact bonds (DIBs), have emerged. Technically, a social impact bond is not a bond at all. It may not be feasible for a government to issue an ordinary bond when it seeks capital to implement a project for which there is neither a budget nor political will. However, a SIB promises to repay the investors only if the project achieves agreed outcomes, which makes the project both financially viable and politically feasible. It provides upfront funding paid for by public savings derived from the ultimate success of the project, if that success indeed materialises.

Take malaria, for instance: the costs of malaria treatment, medication, hospitalisations and deaths can be quantified. If the target is 10% fewer malaria cases, a monetary value can be attached to this, and governments can issue SIBs. Investors buy these bonds knowing that they will get the face value back with interest if the goal is achieved. If the project does not meet targets, they get nothing back and the money is wasted. But it is private risk capital that gets burnt and not public money. If the project meets targets, donor funds or tax coffers will pay back the investors with interest. Management consultants McKinsey describe a SIB as a “partnership in which philanthropic funders and impact investors—not governments—take on the financial risk of expanding preventive programmes that help poor and vulnerable people. Non- profits deliver the programme to more people who need it; the government pays only if the programme succeeds.”

Unlike a bond or a donation, a SIB is therefore a true investment on the part of the funder similar to buying a share in a private company: returns are dependent on the success of the project; total loss is possible in case of failure.

An early example of such a bond was issued by Social Finance, a British non- profit funding agency, to One Service, an organisation that aims to reduce recidivism rates among repeat offenders in the city of Peterborough, England. Preliminary results are encouraging. Projects are being piloted in the UK and the US in areas such as criminal justice, homelessness and unemployment. The Centre for Global Develop- ment, a US think-tank, is working with Social Finance to extend this concept to development aid, such as public infrastructure or healthcare interventions in poor countries.

It has established a working group to design and assess development impact bonds. They differ from SIBs in minor respects, most notably in how investors are repaid. While governments typically repay SIBs, donors or international aid agencies would repay investors in DIBs. As with SIBs, case studies are only in their early stages, but AngloGold Ashanti, the world’s third largest gold producer, and Nando’s, a South African restaurant chain, are working with management consultancy Dalberg Global Development Advisors and are piloting impact bonds to help combat malaria in Ghana and Mozambique.

“This model is a true test of non-profits working with and understanding the performance-based metrics of the private sector,” comments Blair Emily Miller, of the MDG Health Alliance, a coalition of private sector leaders focused on accelerating progress towards the UN’s Millennium Development Goals. “If this works it could unlock a tremendous amount of capital to help scale the non-profits that are providing the most value in the marketplace.”

Unlike bureaucratic government or non-profit agencies, the private sector is often successful because it encourages competitive innovation, results-oriented incentives and a decentralised information flow. DIBs and SIBs aim to replicate these characteristics. For the first time in 50 years, and after trillions of wasted dollars, the foreign aid problem Messrs Easterly, Deaton, Ms Moyo and many others so clearly identify might be solved. Impact bonds have the potential to save development aid, by delivering not only aid, but development too.