Vaccines: a Western plot to make Africans sterile?

Cultural resistance to vaccines wreaks havoc in developing nations

by Ivo Vegter

Nigeria is on the verge of being declared polio-free. Jean Gough, the UN’s children’s agency (UNICEF) representative in Nigeria made this optimistic assessment to journalists in early September 2013. It comes at a time when only three countries remain endemic hosts to the poliomyelitis virus: Nigeria, Afghanistan and Pakistan. Most other countries in which it occurs, known as “importation countries” (because outbreaks are brought in by travellers from endemic countries), are in Africa.

Last year, fewer than 250 polio cases were reported worldwide, according to the Global Polio Eradication Initiative (GPEI). This incurable disease causes irreversible paralysis in about one out of every 200 cases, and death in a tenth of those. It used to be much worse.

The GPEI, a multinational body, was launched 25 years ago, when the disease was endemic in 125 countries and affected 350,000 people annually. Its near- eradication, the GPEI claims, has saved 10m children from paralysis.

News that nine female polio vaccination workers were shot to death in Nigeria’s Kano province in February 2013 rocked the healthcare world. It brought into sharp focus the continued cultural resistance against efforts to eradicate this dread disease in one of its last strongholds.

A decade ago religious leaders in Nigeria made news with a call to resist vaccinations, claiming that they were unsafe and designed to cause sterility. Sheik Suleiman of the Kaduna State Council of Imams and Ulama, and Zubairu Sirajo of the Supreme Council for Sharia in Nigeria told journalists in 2003 that their doctors had conducted extensive research on vaccines. “It is a plot by the Western world to reduce the population of Nigeria and other developing countries,” they said.

Six years later the UN reported that progress was being made against cultural resistance, but that there were also alarming signs that the disease was spreading again. More than 30 cases were reported in Benin, Burkina Faso, Côte d’Ivoire, Ghana, Mali, Niger and Togo in 2009. Of these West African countries, only Niger had reported any cases at all between 2004 and 2008.

This year’s attack may have been the work of militant Islamist group Boko Haram, according to unnamed analysts quoted by the BBC. “Boko Haram” translates as “Western education is forbidden”. This suggests that the motive for hostility to vaccination programmes remains similar.

It may appear strange to foreign observers that such obviously paranoid rhetoric finds a sympathetic hearing in Africa, but Jemila Hamisu Maiyali, a reporter for Nigeria’s Freedom Radio, attributes the conspiracy theory to colonialism, fears about the constituents of vaccines spread by anti-vaccine activists, and the intrusive door-to- door nature of the vaccination campaign to reach “the last child”.

The attack has curbed community outreach programmes, according to Ms Maiyali, and restricted vaccination programmes to clinics and hospitals, which health experts fear may be undermining the effort to obliterate polio.

Polio could become the second human disease eradicated successfully by vaccines if the battle to eliminate polio in Nigeria is as successful as Ms Gough hopes and if the South Asian subcontinent, which faces challenges of its own, follows suit.

The first successful vaccine was for smallpox, which the World Health Organisation officially declared eradicated in December 1979. In the 18th century, it was said that mothers counted their children only after they had survived this dreaded disease. An English country physician named Edward Jenner had heard folklore that milkmaids who had been exposed to cowpox did not get smallpox. Testing the theory, he injected an eight-year-old child named James Phipps with fluid extracted from a cowpox pustule. When the procedure made James immune, Jenner presented his theory about “vaccination” (from “vacca”, Latin for “cow”) to the Royal Society. He went on testing the idea, including on his own one-year-old son.

Mr Jenner rivals Alexander Fleming, the discoverer of penicillin, in the number of lives his discovery is credited with saving. However, in his time the clergy denounced him and the press ridiculed him in much the same way today’s resistance to vaccination manifests itself.

Vaccines have saved some 10m lives per year and brought other diseases under control, including diphtheria, tetanus, yellow fever, whooping cough and measles, according to UNICEF. Progress is being made against several more, including hepatitis A and B, tuberculosis, rotavirus (a common cause of diarrhoea), typhoid fever and human papillomavirus, which is a potential precursor to cervical cancer.

Like Mr Jenner’s experiments, modern vaccination programmes remain controversial in some sectors of society. Those who oppose it on religious grounds, such as the Nigerian imams, are often aided by Western arguments against vaccinations. The most infamous of these was the sensational 1998 study linking the measles vaccine to autism in children. It took 12 years of dogged journalism, primarily by Brian Deer of the UK’s The Sunday Times, to expose the study’s author, Andrew Wakefield, as a fraud. This led to his removal from the doctor’s roll, and the medical journal The Lancet to withdraw the study.

Western fears about discontinued ingredients like thimerosal (a preservative

containing mercury which, contrary to Mr Wakefield’s claims, never did cause autism), or trace elements such as the hormones oestrogen and progesterone (which are also used in contraceptive drugs) play into vaccine resistance in countries like Nigeria, according to Ms Maiyali.

Recent reports in the New England Journal of Medicine that vaccines may not be effective against a new strain of whooping cough have also fuelled speculation about “vaccine-resistant pathogens” by anti-vaccination campaigners. The idea is modelled on the well-documented resistance some bacteria evolve to drugs like antibiotics.

However, this view confuses treatment with pre- vention, according to Aeras, a non-profit biotech research institution that focuses on tuberculosis. On the contrary, the best hope for diseases that have become resistant to drug therapy is prevention through vaccines.

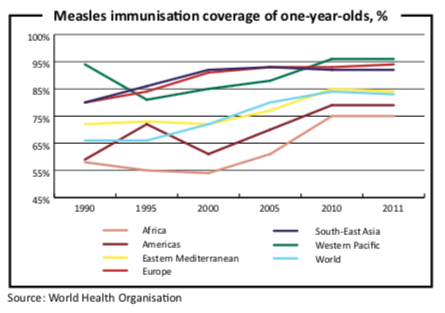

Such popular fears and misinformation about vaccines have led to a resurgence in some vaccine preventable diseases. For example, William Moss and Diane Griffin, of the Johns Hopkins University School of Public Health’s epidemiology department, drew a correlation between vaccination rates and measles outbreaks. They concluded that worldwide failure to maintain high levels of vaccine coverage is threatening progress against measles in a paper published in The Lancet in 2011. They reported that measles cases in Africa rose almost five-fold between 2009 and 2010. The World Health Organisation recorded alarming outbreaks in the Democratic Republic of Congo, Ethiopia, and Nigeria in 2011, in addition to high- profile outbreaks in developed countries in Europe and the US.

If cultural resistance to vaccines remains strong, argues Bill Ahearn, director of research at the New England Centre for Children, the media are largely to blame. “The impact of the media’s coverage of this issue has had a significant and detrimental influence,” he wrote in a paper published in Psychology Today magazine. “Unfortunately, highly improbable events, extraordinary claims implying a conspiracy, and steadfast beliefs with little support beyond anecdote tend to be given more coverage than sound information based upon empirically valid and peer-reviewed research.”

This is true not only in the West, but also in Africa. Except that in Africa, it kills more people.