East Africa’s railways

New tracks and lines are steaming ahead

by Joel Macharia

Rail transport in East Africa is steaming ahead. As the region’s economies recover from slumps that afflicted them in the 1990s from a combination of mismanagement and a decline in commodity prices, their respective governments are fast-tracking new infrastructure to ease the movement of goods, services and people, a crucial requirement for growth.

The Djibouti-Ethiopia Railway was opened in July 2013, running 656km from the city of Djibouti on the Red Sea to Addis Ababa, the capital of landlocked Ethiopia. In April, Tanzania began looking for investors for the Mwambani Port and Railway Corridor (MWAPORC), a project that includes laying a new railway capable of transporting unusually large and heavy cargo to link this Indian Ocean harbour through Uganda to the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC). This project is part of Tanzania’s goal to become the leading entry and exit point into landlocked Central Africa.

Construction of Kenya’s Lamu Port–Southern Sudan–Ethiopia Transport (LAPSSET) corridor began in February 2012. When finished, expected in 2015, it will be a rail, road and pipeline combination running from Kenya’s Lamu port on the Indian Ocean to non-coastal Ethiopia and South Sudan. Kenya is also widening the current narrow-gauge Kenya-Uganda line from Mombasa at the Kenyan coast to the Ugandan capital, Kampala, to standard gauge, as well as building commuter-rail networks for public transport serving Nairobi, Kisumu and Mombasa and their environs.

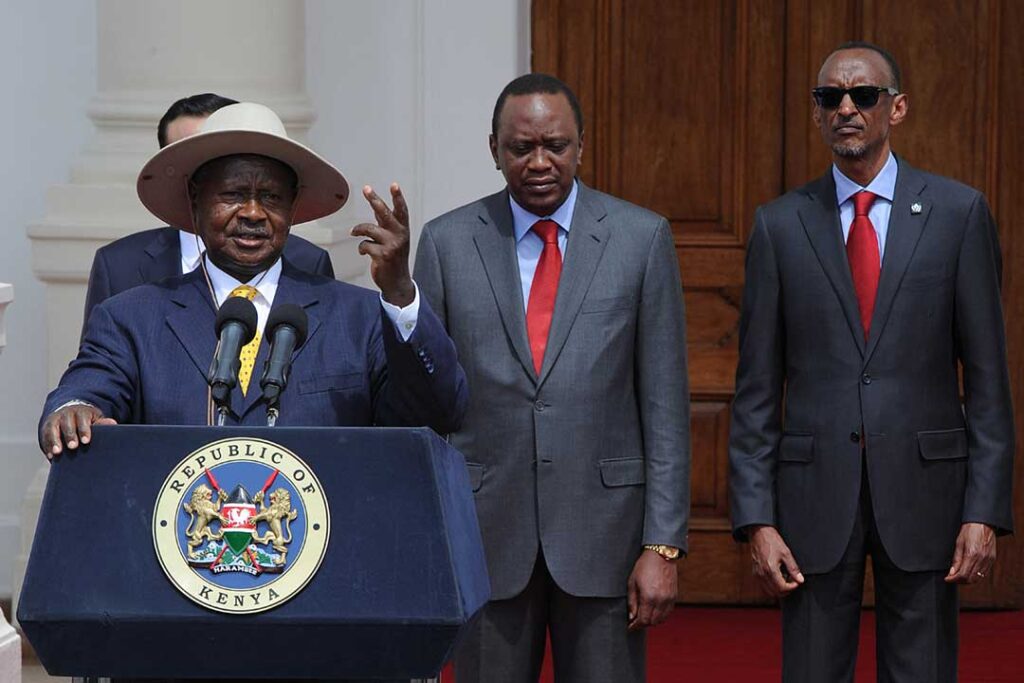

Most recently, the governments of Kenya, Uganda and Rwanda announced last July that they would jointly build a new $13.7 billion standard-gauge railway that will run from Mombasa through Kampala (following a path similar to that of the extended Kenya-Uganda Railway completed in 1927) and then on to Rwanda’s capital, Kigali. The project’s goal is to increase the rail freight capacity from the current 5m metric tonnes on the existing line to 28m metric tonnes on the new line.

However, as Kenya’s government embarks on these ambitious projects, one cannot help but wonder how it intends to administer new transport links when it has failed to manage the existing 112-year-old railway, the Uganda line, named for its ultimate destination. The British built it at the height of the scramble for Africa during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. It links Mombasa with Kisumu, formerly Port Florence, on Kenya’s western edge of Lake Victoria. From here, steamships would travel to Kampala, Uganda’s capital.

When this legendary line celebrated its 100th birthday in December 2001, Daniel arap Moi, Kenya’s president, held a party in Kisumu and invited Benjamin Mkapa and Yoweri Museveni, the presidents of neighbouring Tanzania and Uganda.

None of the heads of state arrived by train, a poignant indicator of the railway’s dreadful situation. Messrs Moi and Museveni both flew while Mr Mkapa came by road.

Since then, the rail line’s troubles have gotten worse. Over the past ten years, the Kenya Railway Corporation (KRC), charged with operating and maintaining the railway, has been declared bankrupt three times, once by the auditor general and twice by transport ministers. Freight on the railway line in 2012 was at its lowest in 35 years and only three of the ten lines that had been added over the years were running.

The railway was originally meant to be the economic artery of East Africa and to solidify Britain’s presence in the region. At the source of the Nile, Uganda was one of the British Empire’s most important colonies.

However, when the Imperial British East Africa Company proposed building a 657- mile (1,057km) train line from Mombasa at the Kenyan coast to the eastern shore of Lake Victoria, the idea met severe criticism.

Media dubbed the proposed Uganda railway a “lunatic line” for two reasons: its outrageous cost at the time, £3,685,400 in 1894 (the equivalent of today’s £384m or $599m); and the difficulty in laying track through the rugged terrain, which would drive anyone demented. The name stuck and the train service from Mombasa to Nairobi to Kisumu became known colloquially as “the lunatic express”, while Africans dubbed it the “iron snake”.

Tropical disease, shortages of labour and water, treacherous topography and hostile local tribes hindered its construction, which began in Mombasa in 1896. Two years later all building stopped when two man-eating lions terrorised labourers for nine months and killed 28 people. A construction supervisor eventually killed the beasts and had their skins made into rugs. The railway line made it to Nairobi in 1899 and to Kisumu in 1901.

During its six years of construction, 2,493 men died. Many of the 32,000 workers who arrived in East Africa were from India, where the British had been building and operating trains since the mid-1800s. While most of the Indian labourers returned, about 3,000 remained, creating the East African Indian community that exists today. The railway’s completion not only made white settlement of the East African highlands possible, it shortened the journey from Mombasa to Nairobi from six weeks to 24 hours.

By 2001 the Kenyan portion of the train network had been figuratively off the rails for over 30 years. The total freight carried on the line dropped from 2.28 billion tonne-kilometres in 1980 to 1.49 billion tonne-kilometres in 2000, according to the World Bank.

Freight handled by the KRC would continue to drop, from 2.4m tonnes in 2000 to 1.6m tonnes in 2011. Over the same 11 years, Kenya’s gross domestic product nearly tripled, from $12.6 billion to $33.6 billion. The total amount of freight handled by the Kenya Ports Authority, which runs Mombasa port, the main entry point into the East African region, had more than doubled from 9m tonnes in 2000 to 19.9m tonnes in 2011.

Kenya and Uganda awarded a 25-year management concession to Rift Valley Railways (RVR) in 2005. Five years later, RVR signed a technical and management sub- contract with a Brazilian company, América Latina Logística (ALL), which had overseen the successful privatisation of Brazil’s national railway system. The deal called for ALL to provide RVR with management and operational staff and to oversee the transfer of technology. Despite this assistance, RVR has not been able to stem the rail service’s losses.

“We have had a seven-year concession, and since it started, cargo transported by rail has gone down from 15% to 3%,” said Michel Kamau, Kenya’s transport minister, in an interview last May. “We will look at the concession again and see whether it is working.”

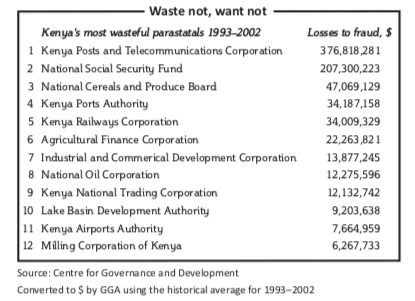

Politicisation and poor corporate governance were the leading factors that contributed to the KRC’s near derailment, according to a 2005 report by Kenya’s Centre for Governance and Development, a non-profit research group. Kenya’s president controlled senior management and dished out these posts to his pals who were not necessarily the most competent individuals. The problem was compounded by bad laws, weak supervision, lack of adequate resourcing and institutionalised impunity, such as power held by Kenya’s president to declare certain companies exempt from auditing.

The research group’s study documented parastatal profligacy from 1993 to 2002. It identified Kenya Railways as the country’s fifth most wasteful state- owned enterprise, having squandered an estimated $34m during this decade. A deficit of $1.4m in 1990 grew to an astonishing $50.8m by 1997. By 2002, KRC owed $284.5m and had been unable to collect $38.8m from its debtors.

The Parliamentary Public Investments Committee, which also reviewed state- owned companies, blamed these losses on inefficiency, ineptitude and corruption in a September 2004 report.

Has Kenya learned any lessons from the runaway losses of the “lunatic express”? The historic train line has made some headway in the last few years with the passage of new laws that provide a sharper legal sting against the mismanagement of state-owned companies: the Anti-Corruption and Economic Crimes Act and the Public Officers Ethics Act, both adopted in 2003; and the Privatisation Act, passed in 2005. The government is now required to prosecute officers who abuse their positions within these state-owned companies.

Despite its troubled history, the romantic allure of the “lunatic express” will probably never be sidetracked. Queen Elizabeth II and Theodore Roosevelt, a former US president, rode it. Winston Churchill shot zebras from the train. As the Kenyan government works to expand its railway infrastructure, it should resuscitate the “lunatic express” before it slides into the sunset of oblivion.