Nigeria’s crumbling infrastructure

Since the 1970s oil boom, the government has not maintained the country’s power stations, roads, railways and airports

by Adeyeye Joseph

Apapa, Nigeria’s busiest seaport, is a bustling complex of berthed ships, container yards and fuel depots in Lagos, the country’s commercial capital. A poorly maintained 27.5km road, which often floods, links this harbour to the rest of the West African nation. Trucks use this vital economic artery to freight imported goods from the Nigerian coast to the hinterland and return with cocoa beans, rubber and peanuts to export. But driving to and from this port means navigating around huge potholes, sometimes the size of a small pond.

In 2010, the Nigerian federal government contracted two of Nigeria’s biggest construction firms, Julius Berger and Borini Prono, to fix the road. Three years later, repair works have nearly ground to a halt and hope has turned into despair. The two contractors have since accused the government of starving the project of much needed funds.

The story of Apapa and its roads is archetypal of Nigeria’s run-down infrastructure. Most of the roads, power stations, refineries, railways, airports and public utilities in Nigeria were built or started in the 1970s during the country’s oil boom. But successive governments did not place much premium on maintenance and these infrastructures are now decrepit. Between independence in 1960 and now, about half a dozen national development plans have been launched in Nigeria. But they were all poorly executed. Now individual ministries are preparing and executing sector-specific plans aimed at tackling the country’s infrastructure problems.

Last year President Goodluck Jonathan ordered his cabinet to weld these plans into a National Integrated Infrastructure Master Plan (NIIMP). Mr Jonathan made this decision after commissioning the African Development Bank (ADB) to review the country’s infrastructure and to provide a framework for an integrated plan.

The ADB’s report, “An Infrastructure Action Plan for Nigeria”, released last July, revealed that the country’s infrastructure was broken down and needed urgent fixing. Only 18% of Nigeria’s 197,000km road system is paved, according to the report. “It is estimated that 40% of the federal primary road network is in poor condition or worse, and therefore in need of rehabilitation; 30% is in fair condition and in need of periodic maintenance; and about 27% is in good condition.”

Nigeria’s rail network is over 100 years old and only 25% of its trains were operational as of 2007, while just about 50% of the coaches were in good condition, according to the report. Air safety has improved only slightly in Nigeria and navigational aids and air traffic control facilities only became adequate after a major upgrade in 2006.

“Most regional airports lack appropriate apron lighting facilities [where aircraft are loaded, unloaded and refuelled] and thus limit aircraft and airport utilisation to 12 hours daily,” the report says.

The report cites the phenomenal growth of Nigeria’s telecommunications sector in the last decade, but adds that the system is plagued by service quality problems.

The report’s evaluation of the Nigerian power system is the one that is likely to resonate most with the average Nigerian. “Current available electricity generation capacity is nearly 50% below estimated power demand,” according to the report. Electricity is a touchy issue in Nigeria. Consumers outraged by fraudulent bills or poor supply have been known to assault electricity company workers.

On its website, the Nigerian presidential task force on power, a government committee, estimates that government-owned plants have an installed capacity of 6,978 megawatts (MW). The plants only generate about half, a measly 3,500MW annually, for the country’s estimated 160m people. The figure is significantly lower than the country’s estimated power demand of 10,000MW to 20,000MW.

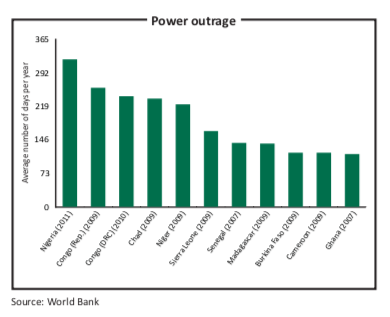

The ADB report drew copiously from a plethora of previous reports on Nigeria’s electricity deficit. A government panel, the Vision 2020 committee, prepared a report in 2009 which found that only 40% of households were connected to the national grid. Enterprise surveys, the ADB says, have also shown that Nigeria experiences outages on an average of 320 days a year.

Nasir el-Rufai, a former minister and staunch critic of President Jonathan, has often argued that Nigeria’s infrastructure deficiencies are some of the country’s most debilitating development problems.

“The lack of infrastructure explains why Nigeria’s cost of production has remained extremely high while industrial productivity has declined,” he wrote in a 2011 article. “It explains why we spend 1.3 trillion naira [$8.6 billion at 2011 exchange rates] on food imports while our farmlands lie fallow; it is the reason why we lose lives every day to accidents and preventable diseases. Infrastructure deficit is why we are where we are today.”

Government ministers, however, have expressed optimism that the new master plan will be a game-changer. They are holding financial road shows across Nigeria to drum up support for the NIIMP. At one such event last July, Shamsuddeen Usman, Nigeria’s national planning minister, gave a breakdown of the funding component of the NIIMP.

“The NIIMP will require an estimated $2.9 trillion to close Nigeria’s huge infrastructure gap in the next 30 years, 52% of which will come from the treasury, while the private sector is expected to cover the balance of 48%,” Mr Usman said.

For the priority projects, $800 billion will be used to improve the transportation sector; $900 billion will be expended on energy projects; $300 billion on information and communications technology (ICT); and $350 billion on agriculture, water and mining projects. Another $500 billion will be invested in housing, security and other social infrastructure.

Some of Nigeria’s bilateral and multilateral partners are backing the NIIMP. The World Bank’s International Finance Corporation (IFC) has committed to launch a $1 billion bond to help fund infrastructure projects. The Islamic Development Bank and the African Finance Corporation have also shown interest.

At the road show, Mthuli Ncube, the ADB vice-president, said the lender’s interest in the NIIMP was part of a larger plan to bring about the transformation of the African infrastructure landscape.

“Africa is transforming but we want it to transform faster,” he said. “In 2000, the GDP of Africa was about $600 billion and today it stands at over $2 trillion. However, it still has challenges of youth employment and inequalities. We recognise Nigeria’s effort to address the issues, in spite of its large population. We believe that in 30 years to 40 years, it will succeed in doing so.”

While Nigeria seeks to attract foreign investment, it is also turning to its sovereign wealth funds, pension funds, proceeds from the sale of public companies and the stock market as alternative sources of funding.

Foreign loans, however, are a funding source that may prove unpopular among Nigerians. In recent times Nigeria’s rising external debt portfolio has stirred a huge debate in the country. So much so that the country’s finance minister, Ngozi Okonjo- Iweala, had to address a press conference in June to clarify matters. “Our external indebtedness,” Ms Okonjo-Iweala explained, “is as low as $6.67 billion or about 3% of gross domestic product.”

Many Nigerians are worried that the country’s external debt burden may soon equal the high indebtedness of previous years. Nigeria pleaded and won an $18 billion debt write-off in 2005 from the Paris Club, a grouping of 19 rich countries that handles state-to-state debts, but only after clearing $12 billion in outstanding debt.

Even as Nigerian officials prepare the ground for the implementation of the NIIMP next year, some Nigerians have canvassed for a more holistic solution to the country’s infrastructure woes. The governor of Lagos State, Babatunde Fashola, is one. He wrote a letter last year to Mr Jonathan asking to him to speed up the reconstruction of Apapa’s main thoroughfare.

At an event last June in Jos in northern Nigeria, Mr Fashola said Nigeria needed to focus on three types of infrastructure. “One is physical infrastructure, such as roads, bridges, schools, hospitals, etc.,” he said. “The second is intellectual infrastructure, such as science, research, ICTs, etc. But the most important is moral and social infrastructure. Physical and intellectual infrastructures are useless without a strong value system.”