Mobile banking

by Tolu Ogunlesi

More people in Africa use their mobile phone to bank than in any other region in the world. The continent’s banking revolution began in March 2007 when Kenyan telecoms operator Safaricom launched M-Pesa, a service that allows users to send, receive and save money using a cellphone. Since then M-Pesa has spread to Rwanda, South Africa, Tanzania and Uganda. Mobile banking now exists in 33 African countries, according to GSMA, a trade association.

Mobile phone technology is especially useful in banking where many people live in rural areas far from cities where most banks are located. Gone are the days when it was necessary to visit a bank building to deposit or withdraw money. Phones now act as virtual “wallets” and bank accounts, giving people in countries with low traditional banking penetration unprecedented access to financial services. Nigeria, for instance, has 6,000 bank branches for a population of 162.5 million, according to Nigeria’s Central Bank, far fewer than Britain, which has almost 10,000 bank outlets for its 60 million people.

“Accessibility to reach bank branches especially in the rural areas is the main reason for the unprecedented growth and popularity of mobile banking in Africa,” said Peter Ondiege, an economist with the African Development Bank, at a 2012 conference on mobile financial services.

Portable handsets are ubiquitous. Across the continent mobile phone penetration far outstrips banking penetration. Figures released in January 2013 by the Nigerian Communications Commission show that there are now more than 110 million “active (mobile) lines” in Nigeria, compared to less than 25 million bank accounts. Converting mobile phones into “e-wallets”, or virtual bank accounts, is an easy way to ensure that as many people as possible can make payments, transfer funds and save.

A 2010 study by the Consultative Group to Assist the Poor, a research centre in Washington DC, found that branchless banking, which relies on retail agents and information and communications technology like mobile phones, was overall 19% cheaper than comparable bank services. The lower the value transacted, the higher the saving, at 38% for the lower values poor people are likely to transact.

Mobile phones are also used to send cross-border remittances. For instance, M-Pesa allows Kenyans in the UK to send money back home. Once the necessary technology spreads throughout Africa, mobile phones will make sending and receiving remittances internationally cheaper and easier, too.

In 2012 GSMA surveyed 78 mobile money service providers, which it said represented more than 60% of the world’s total. This survey revealed that nearly 70% of the world’s registered 81.8 million mobile money customers are in sub-Saharan Africa. These 56.9 million people had a registered mobile money account in June 2012, more than twice the number of Facebook users in the region.

Kenya is the global model for this innovative use of mobile banking technology. When M-Pesa was launched, Kenya had more than two million bank accounts, a figure that M-Pesa says it reached by the end of its first year. Two years later, in 2009, there were more M-Pesa subscribers than bank accounts, according to Njuguna Ndung’u, governor of Kenya’s Central Bank. Six years on, Safaricom claims it has 15 million users conducting more than two million transactions daily. The World Bank estimates the value of these transfers to be about $10 billion a year, equivalent to a third of Kenya’s GDP.

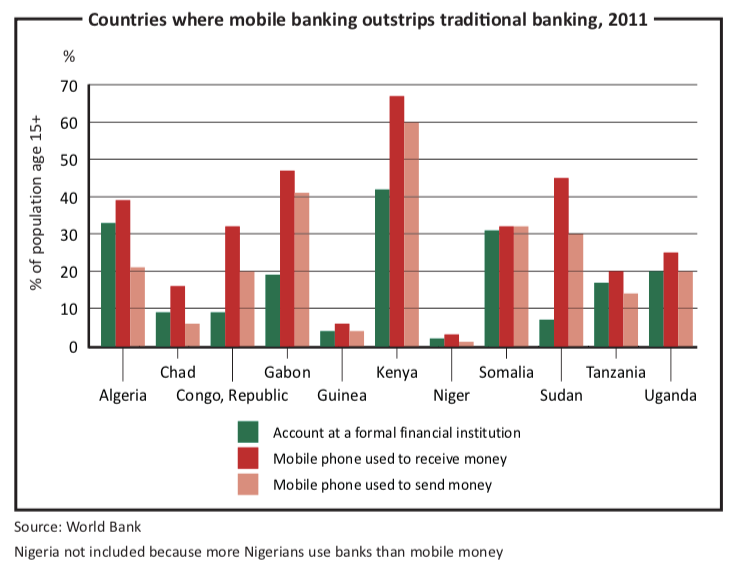

Nigeria’s population of 162.5 million makes it a much larger market than Kenya’s 41.6 million. Its GDP, $244 billon, is seven times larger than Kenya’s $33.6 billion, based on World Bank figures. Yet it remains well behind Kenya in the adoption of mobile banking. According to the World Bank, 60.5% of Kenyans aged 15 and older have used a mobile phone to send money compared to Nigeria’s 9.9%, and 66.7% of Kenyans have received mobile payments, compared to Nigeria’s 11.2%.

Why the huge difference? Part of the answer may be that Kenya got a head start; Nigeria only began issuing mobile banking licences in 2011, four years after M-Pesa kicked off.

A 2012 Brookings Institution report acknowledges that “replication [of M-Pesa] in many cases has proven harder and slower [than in Kenya]”. It highlights a 2011 International Finance Corporation study that “identified no fewer than 50 parameters that determine the potential for mobile money’s successful development in a given country”.

Deji Oguntonade, head of electronic payment solutions at Nigeria’s GTBank, echoes this view. “Every country is different. We should look at the dynamics of the country to fashion out where things should go,” he says.

The regulatory landscape in Kenya is also much more liberal than Nigeria’s. Only one mobile phone company, Safaricom, can claim credit for Kenya’s mobile banking revolution. It created this successful platform alone, without the help or hindrance of banks. Only recently has Safaricom started partnering with banks to develop new products for customers.

Nigeria on the other hand is kicking off with a system that places financial institutions and “corporate organisations” — collectively known as mobile money operators (MMOs) — at the core of mobile banking services. At the same time, it prohibits mobile phone companies, referred to as mobile network operators (MNOs), from applying for mobile banking licenses.

The mobile phone companies are expected to serve only as technology partners to the financial institutions, providing the technical infrastructure for the licensed MMOs. A December 2011 directive from the central bank reiterated that “no telecommunications company [has] been licensed by the central bank to operate any mobile money scheme in Nigeria.”

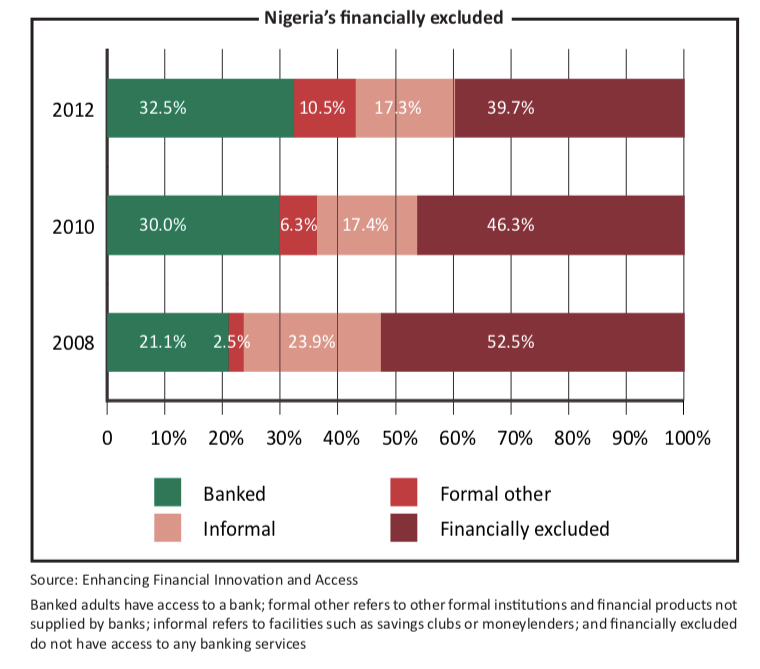

As could be expected, the mobile phone companies were at first critical of the policy, but have since gone into partnerships with the licensed mobile money operators. The potential for Nigeria is immense, mostly because of the size of its population (Africa’s largest), and the size of its unbanked population. A 2012 survey by Enhancing Financial Innovation and Access (EFInA), a Lagos-based non-profit group, reported that only 28.6 million people (32.5% of Nigeria’s 87.9m adults) own or use a traditional bank account. In addition, 40% of adult Nigerians are “financially excluded”, meaning they neither own nor have any access to any traditional banking services, financial industry products (insurance, pension schemes, stockholding) or informal contributory savings schemes.

Only 5.5% of Nigeria’s adult population are currently aware of the existence of mobile money operators, according to the EFInA report. Only 0.5% are registered users of mobile money platforms (mostly to purchase cellphone airtime), a far cry from Kenya, where two-thirds of the adult population are registered.

Pagatech, one of Nigeria’s leading mobile money operators, says it crossed the 500,000-user mark in March 2013, two years after its February 2011 launch. By Nigerian standards these are insignificant numbers, but Pagatech’s goal is ambitious: it plans to reach 15 million users by 2015.

Traders, farmers and the unemployed form the bulk of this financially-excluded class, according to the EFInA survey, which questioned 20,000 adults in Nigeria. The challenge is therefore for the mobile banking operators to focus on developing products for these sectors.

Following the success of other mobile banking operators in Africa, Nigeria’s mobile money operators will have to shift their focus from the country’s saturated urban areas and concentrate on the rural areas where more than 70% of the population lives. This requires building vast networks of “over-the-counter” agents in supermarkets, fuel stations, grocery stores and other convenient locations to receive cash deposits, load them onto mobile phones and issue pay-outs on demand.

Innovation and deregulation will be the big lessons to learn from Kenya. M-Pesa has consistently introduced new services to expand its customer base. One of its most recent innovations is M-Shwari (cool or calm in Swahili), which allows customers to operate their mobile phones as interest-earning savings accounts.

Nigeria’s Central Bank has said that its goal is to reduce Nigeria’s unbanked population by at least 20% by 2020. GTBank’s Oguntonade thinks this is a realistic goal. He oversaw the rollout of SMS and internet banking more than 10 years ago and is considered one of the pioneers of electronic banking in Nigeria. He is optimistic about the future of mobile banking in his country. “Once the value is there, Nigerians adopt technology very quickly,” he says.