In 2000 Zimbabwe’s president, Robert Mugabe, began seizing the country’s white- owned commercial farms. He promised to give them to the landless. Instead he gave much of this land to his wealthy cronies, wrecking the country’s largest industry.

by Tony Hawkins

The story of Zimbabwe’s land resettlement began in 2000 when Robert Mugabe released his dogs of war to evict white commercial farmers from their land.

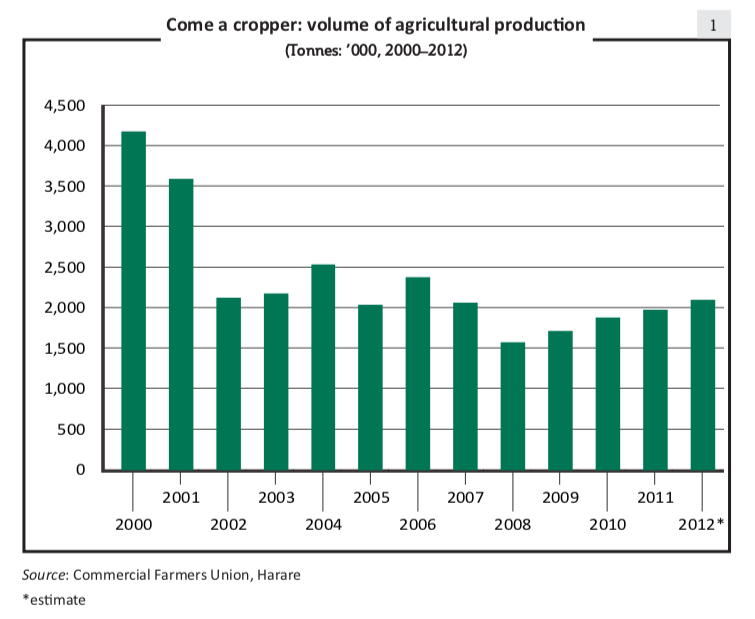

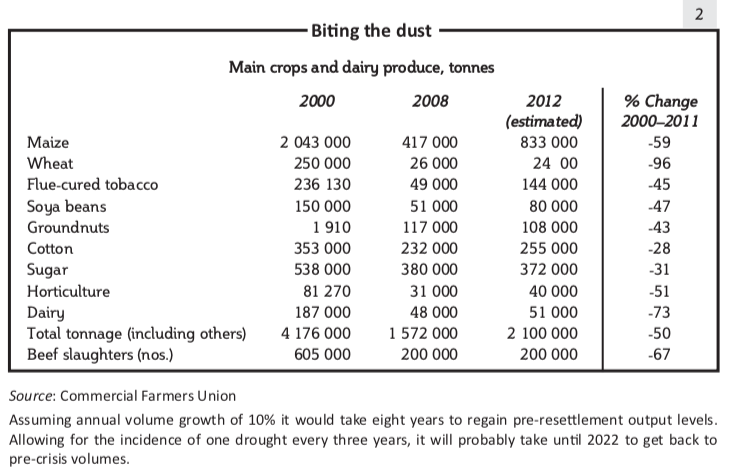

That year the country’s farmlands yielded some 4.2m tonnes of agricultural produce, according to the Commercial Farmers Union (see chart below). But by the end of this country’s “lost decade”, 1998 to 2008, agricultural output had slumped more than 60% to 1.6m tonnes. The estimate for 2012 is 2.1m tonnes—half of what was produced 12 years ago.

Were that the sole statistic for measuring the achievements of land resettlement, it would be bad enough. But when the impact on the economy as a whole is taken into account, the picture is far bleaker.

Zimbabwe’s real GDP fell 40% from $6.6 billion in 2000 to $4.1 billion in 2010, while real per capita incomes in 2011 were 37% lower than when Zimbabwe finally gained independence from Britain in April 1980, according to the World Bank.

Despite these harsh truths there is no shortage of apologists determined to gainsay them. These range from itinerant United Kingdom academics seeking to establish a reputation for themselves using specious, carefully-sanitised case-study data to the political scientists, journalists and politicians determined to prove that sub- Saharan Africa would be a better place without commercial agriculture.

The data in chart 1 and chart 2 put the debate into context. It is true that if the official data are to be believed—and they come with a very serious health warning—in 2011 there were some 700,000 people employed on re-settlement farms, double the number ever employed in commercial agriculture before 2000. But there is very little in these data for land reform apologists to celebrate. For a start, the figures for 2010 show that a year earlier there had been 1.15m people employed on these same farms and that some 450,000 jobs had disappeared in just 12 months.

Then there are the wage numbers. Farmworkers on resettled properties were earning $10 a month in 2011 in an industry where the minimum official wage is $80 monthly, according to the Zimbabwe National Statistics Agency. The average wage outside agriculture is $530 a month, which also speaks volumes for the “success” of resettlement.

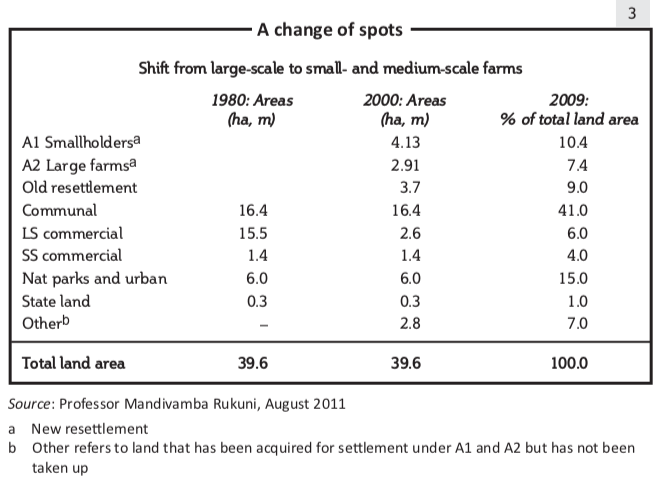

Chart 3 illustrates the radical shift in land ownership. At independence in 1980, large-scale commercial farmers, almost all of them white, owned 15.5m hectares of land, or 39% of the total, predominantly in the regions of the country with better climates and soil. The bulk of the rest was owned communally (41.4%) while urban/ national parks and other state-owned land accounted for a further 15.9%, leaving small-scale non-communal farmers occupying just 3.5% of the total.

Following the completion of the land programme in 2009, resettlement farmers occupied 26.8% of the land while the share of large-scale commercial growers had been reduced to 6%. The communal share was unchanged at 41%, as was the share of parks and state-owned land at 15.9%.

A degree of equity in land occupation—though not ownership—was achieved, albeit in an extraordinarily arbitrary and unfair way. The Zimbabwean media is full of reports of multiple farm ownership by prominent politicians, judges, bureaucrats and army, air force and police officers. According to the September 14th 2012 edition of the Independent weekly newspaper, Senate President Edna Mazongwe owns six farms, Local Government Minister Ignatius Chombo owns five, Home Affairs Minister Kembo Mohadi four and Indigenisation Minister Saviour Kasukuwere owns two.

Had the process been conducted in a transparent, non-violent and, above all, legal manner, it might have been possible to share the apologists’ view that social gains had been made, albeit at enormous economic cost. But the entire operation was cronyism and political patronage at its worst. Those now on the land do not own it. They can never be certain that a future government will not seek to reverse the process. Even the arbitrarily-distributed social benefits are cloaked in insecurity and uncertainty.

Worse, the programme lacked economic rationale. The original aim in the early 1980s was to reduce the overcrowded population on communal lands to some 350,000. But by the early 1990s, after a decade of lacklustre progress in land resettlement, there were over 1m families eking out a precarious living as subsistence farmers.

For land resettlement to work, the government should have opted for a multi- pronged approach. For a start, it needed to raise productivity and living standards in the communal areas, not just by reducing the population there, but also by investing in infrastructure and skills development. At the same time, as people were moved out of these areas, they should have had either a place—or better still—a job to go to. This did not happen. When fast-track land resettlement took off, the government simply allocated land—or allowed people to evict the owners and settle—without funding, without extension support and without infrastructure. The programme was programmed to fail, as it duly did.

This was hardly surprising. A government bureaucracy which has proved unable to operate a customs post at Beitbridge on the South African border, or a passport office in Harare, was never going to make a success of a highly-complex and technical task such as land resettlement, especially since it was starved of funds.

A further aspect, neatly captured by Daron Acemoglu and James Robinson in their 2012 book “Why Nations Fail: The Origins of Power, Prosperity and Poverty”, was the conduct of “extractive” institutions (their term) as distinct from inclusive ones. “Extractive political institutions concentrate power in the hands of a narrow elite and place few constraints on the exercise of power. Economic institutions are then structured by the elite to extract resources from the rest of society.”

In Zimbabwe extractive institutions in the form of cronyism in land redistribution, in the exploitation of diamonds and in access to bank loans, municipal land and government contracts worked to the advantage of the Zanu-PF elite. Recent media reports and anecdotal evidence show that some in Morgan Tsvangirai’s Movement for Democratic Change have been quick to leap aboard the same gravy train. Until Zimbabwe’s society becomes more pluralistic and its institutions more inclusive, little will change.

The apologists have seized on structural change in the tobacco sector to justify their claims that—given time— land resettlement will succeed. In 2013, according to the state Tobacco Industries Marketing Board, there will be more than 50,000 registered tobacco growers, all but 800 of them small-scale. In 2012 resettled farmers produced 42% of the crop, while 750 large-scale commercial farmers grew 29%. Communal farmers and small-scale commercial producers grew a further 29%.

Within a few years—since 2007—the centre of gravity in the tobacco industry has swung from large to small scale, fuelled in part by the extension of contract farming to smallholders. With this shift, quality and productivity have declined. The proportion of below-average quality tobacco rose from 16% in 2001 to 35.5% in 2010. Over the same period, yield per hectare for the entire industry tumbled 20%.

In a dollarised economy, exporters cannot look to currency devaluation to offset this combination of declining productivity and deteriorating quality. This is where the smallholder tobacco models are falling short. So long as smallholders can minimise costs by ”employing” family labour, failing to pay minimum wages and cutting down trees to cure tobacco rather than buying coal, tobacco will probably remain a profitable crop. But Zimbabwe’s tobacco reputation was built on producing high-quality leaf. If this prestige is tarnished, the country will continue to lose share at the top end of the market.

Whatever its socio-political impact, land reform represented a step backwards in terms of productivity, efficiency and competitiveness. At a time when agriculture throughout the world is moving away from smallholder farming to integrated value- chain production units, dominated by commercial growers, mostly on medium-sized and large farms, Zimbabwe is heading in the wrong direction.

Zimbabwe gave up its technological lead in agriculture and made itself more dependent than ever on low-cost production. This has translated into low wages, as is already the case on resettlement farms. Or it could also lead to increased technology and mechanisation, which will mean higher unit costs and fewer jobs in a country with massive unemployment and underemployment. Neither is an optimal growth path for a low-income country, starved of capital, and with extremely high unemployment in excess of 60% of the labour force.

Over time, as economies develop, agriculture’s share of both GDP and employment falls. Workers leave the land for better-paid jobs in the towns and cities. Starved of young able-bodied workers, farms mechanise and productivity rises. There is no reason to expect Zimbabwe’s future growth path to be any different. With a mere 700,000 people currently employed in the formal economy (excluding agriculture and private domestic service), or 14% of the workforce, land resettlement cannot and will not solve the country’s unemployment problem.

Those who expect—hope for?—a return to large-scale commercial agriculture have lost touch with reality. It is not going to happen. No future government is going to evict the settlers. Omelettes simply cannot be unscrambled. The best that can be hoped for over the long haul is a gradual re- commercialisation of agriculture by freeing up land markets and allowing successful smallholders to expand their land ownership. At the same time the state must re-think its policy towards the communal areas by investing in infrastructure and seeking to foster off-farm job opportunities in the field of agri- business.