A new frontier is emerging in the murky world of piracy. The Gulf of Guinea—an area that stretches from West Africa’s Guinea to Angola—is slowly becoming engulfed in what the United Nations (UN) has described as a “catastrophe” with a record number of armed criminal gangs targeting shipping along its coast.

On August 28th a Greek-owned oil tanker carrying 50,000 tonnes of diesel and petrol fuel was attacked off the West African coast of Togo. Pirates seized control of the vessel, took its 23 Russian crew-members hostage and sailed towards Nigeria. It was the eighth such incident or attempted incident off the coast of Togo since January this year.

“For pirates to attack a vessel under anchor really shows that they are getting audacious—it is very worrying,” said Pottengal Mukundan, director of the non-profit International Maritime Bureau (IMB), a division of the International Chamber of Commerce. “Piracy in the Gulf of Guinea is now a serious problem. It is now the second most important high risk area [in Africa], after Somalia.”

Concern about piracy in the Gulf of Guinea has been mounting since the late 1990s, when armed robbers first began targeting high-value assets at sea, particularly shipments of crude oil.

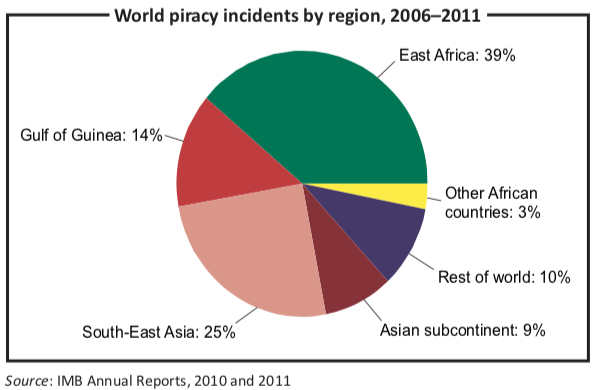

Experts say 2010 was a turning point, however, with the Gulf of Guinea leap- frogging to second position in Africa and sixth place in the world’s top piracy hotspots, according to the UN International Maritime Organisation’s 2010 annual report.

In 2010, 45 incidents were reported across the Gulf of Guinea, followed by 58 attacks in 2011, according to a UN report on piracy in the Gulf of Guinea. Of those, 21 were reported off the coast of Benin, 14 off the coast of Nigeria, seven off the coast of Togo, four each off the coasts of the Democratic Republic of Congo, the Republic of Congo and Guinea, two off the coast of Ghana and one off the coasts of Angola and Côte d’Ivoire.

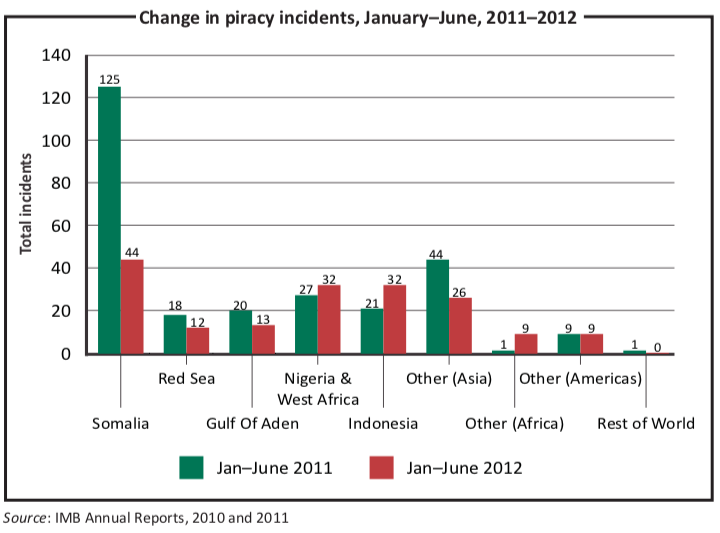

The growth in piracy off the West African coast is even more marked when contrasted with the declining number of incidents in other notorious piracy hotspots, such as the Bay of Bengal near Bangladesh and the Strait of Malacca, a stretch of water between Malaysia and the Indonesian island of Sumatra. Somalia—still the world’s most prolific source of piracy attacks—has also seen incidents decline, from 176 in 2011 to 33 in the first eight months of 2012, according to the European Union Naval Force, which patrols the Indian Ocean.

The history of Somali piracy has led to comparisons with the emerging trend in West Africa, but experts say there are a number of points that distinguish Gulf of Guinea pirates from their Somali counterparts.

“The big danger in the Gulf of Guinea is against loaded product tankers, which are hijacked by criminals and taken to a location where the cargo is illegally discharged into a smaller vessel,” Mr Mukundan said. “Usually the ship and crew are released— although violence is often used against them during the period under [pirate] control. But the ultimate purpose is to steal the cargo, not to kidnap the crew, as is the tendency in Somalia.”

The causes of piracy in the Gulf of Guinea centre on Nigeria—Africa’s most populous nation—whose history of criminal activity around the troubled Niger Delta has proved fertile ground for breeding pirates. But Nigeria has a strong navy and its response to criminal activity off its own coast has been increasingly successful. The UN reported that the number of piracy incidents off the Nigerian coast decreased from 48 in 2007 to 14 in 2011, pushing pirates to waters further along the coast.

On September 5th, pirates hijacked a Singapore-owned oil tanker, the Abu Dhabi Star, off the coast of Nigeria with 23 Indian sailors on board, according to the BBC. Soon after, the Nigerian navy sprang into action and rescued the vessel.

Benin, on Nigeria’s western border, has also been particularly vulnerable, according to the UN’s report. The increase in piracy incidents off its coasts has led the Joint War Committee, a London-based marine insurers’ group, to add Benin to its list of high-risk countries. The result has been increased insurance rates for vessels operating in Benin’s waters, a 70% decrease in ships entering the port of Cotonou, the country’s economic capital, and a 1m tonne drop in tonnage—an estimated loss of $81m in customs revenue per year.

But the implications for the West African sub-region spread far beyond its coastal economies. Piracy also affects trade with neighbouring countries, including the impoverished landlocked states of the Sahel—Burkina Faso, Mali and Niger—which rely on their coastal southern neighbours for vital imported goods.

Some action has been taken by the affected nations. “Operation Prosperity”— a joint patrol programme between the governments of Benin and Nigeria—has harnessed logistical support from Nigeria, including two helicopters, two maritime vessels and two interceptor boats, while Benin uses two ships donated by the United States (US) government.

But the operation confronts considerable challenges, according to a UN report. “The joint operation faces major constraints, including the absence of logistical support facilities for vessels being used to conduct patrols. As a result, the Nigerian vessels participating in the operation must sail to Lagos for refuelling and repairs,” the UN report says.

“To ensure the sustainability of these joint patrols, adequate facilities will need to be constructed in Cotonou to support refuelling, maintenance and storage of supplies used in the joint operations.”

The report also found that the Gulf of Guinea states lack a joint surveillance system, a sustainable process for equipping and funding maritime security, and a formal system for information sharing.

Last year the UN Security Council issued resolution 2018 “expressing its deep concern about the threat that piracy and armed robbery at sea in the Gulf of Guinea pose to international navigation, security and the economic development of states in the region”. The Security Council also called for “a comprehensive solution to the problem of piracy and armed robbery at sea in the Gulf of Guinea”.

The resolution, however, falls short of authorising other states to enter territorial waters to repress piracy. Experts say that the response has been inadequate. To combat piracy off Somalia the UN Security Council called upon states and regional organisations to fight piracy with naval vessels, arms and military aircraft, but “resolution 2018 only expresses concern,” said Tullio Treves, a judge at the International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea and a professor at the University of Milan.

“This may be an indication that [the] Security Council considers the Somalia situation exceptional and not to be taken as a precedent for other situations,” he added. “It seems to me that the main powers are already very much engaged in the situation there and are hesitant to commit further resources in another theatre.”

The US has increased its involvement in recent weeks—with the US navy secretary, Ray Mabus, holding talks with senior military commanders on the training of armed forces for maritime security. France, China and the broader European Union programme on maritime security have also extended help to countries in the Gulf of Guinea.

And unlike Somalia—which is without an effective government—piracy in the Gulf of Guinea affects functioning states, who can draw on the, albeit limited, resources of their own national security agencies.

“Somalia is an exception because of the lack of an effective, recognised sovereign state,” Mr Teves said. “In the Gulf of Guinea, the states could exercise their own power on the territory.”

States affected by piracy have sweeping legal powers to deal with the problem under international law. The law of piracy—set out in the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea and the 1958 Geneva Convention on the High Seas—gives states that intercept acts of piracy on the high seas the right to arrest and detain pirates, seize property, and decide upon penalties.

But experts say that the Gulf of Guinea states need to reform their domestic legal frameworks, which include inconsistent and outdated definitions of piracy and lack offences such as conspiracy and other accessorial liability. There is also a wide variation in the type and seriousness of offences in different countries.

“Research has shown that the penalty for piracy varies very much from state to state, from a few months to long prison terms,” Mr Teves said. “The experience from other regions, like that [in the] Strait of Malacca, that have successfully suppressed piracy in the past is that there needs to be coordinated action and some legal harmonisation to deal with the problem.”

Although Gulf of Guinea states have demonstrated their willingness to act at a governmental level, there is a growing sense that piracy on the high seas often involves the complicity of officials on land, according to the UN report. Pilfered goods —usually fuel—resurface on the black market and are then stolen and distributed with the collusion of officials at the ports.

Whilst internal complicity and corruption is a major issue within their jurisdictions, perhaps the biggest challenge for the Gulf of Guinea states in combatting the growing piracy threat will be coordination with each other. But in a region with so many states, radically differing legal systems and four languages—French, English, Spanish and Portuguese—the task is a daunting one.

“This is a crime, which easily spills over across borders,” said IMB director Mr Mukundan. “Therefore the need for cooperation and information sharing between the countries is great. I can’t overstate its importance.”