Cameroon’s trompe l’oeil unity

One nation’s lingering divisions hold a powerful lesson for Africa

Unification is easy on paper but it takes political will to make it work. Cameroon, still deeply divided along colonial-era language lines, has this lesson to teach the continent. The west African nation’s French-speaking political elite pay lip service to notions of “integration”, but remain unwilling to take the steps necessary to share power with their Anglophone compatriots.

To commemorate the 50th anniversary of the republic’s reunification French- speaking President Paul Biya visited Buea, capital of Cameroon’s English-speaking south-west region, in February this year. The trouble is Mr Biya was three years late: reunification was officially achieved on October 6th 1961, when British Southern Cameroons voted in a UN plebiscite to join La République du Cameroun, which had gained independence from France a year earlier.

Mr Biya had postponed his visit several times since it was first scheduled in 2011. The last time the president set foot in the English-speaking zone was in 2000, after the eruption of Mount Cameroon. His visit, ironically, was designed to symbolise the healing of wounds after a history of French marginalisation of Cameroon’s English-speakers.

Colonial history laid the foundations for this state of dissonance. Cameroon was a German colony from 1884 until 1916, when Britain and France invaded the territory at the height of the First World War.

The two powers divided the territory that year in an agreement called the Picot Partition. France took four-fifths of the area while Britain took a fifth, according to Victor Ngoh’s “The Un- told Story of Cameroon Reunification, 1955-1961”. The British Cameroons were in the north-west and south-west regions, bordering Nigeria, while French Cameroon encompassed all the territory to the east. This partition was internationally recog- nised at the Treaty of Versailles in 1919.

The British and French administrative styles differed greatly, with far-reaching implications for the future unified nation. British indirect rule left day-to-day administration in the hands of appointed native rulers. In contrast, France’s direct rule was hierarchical and highly centralised. The French colonial strategy of assimilation encouraged the adoption of French culture, using language as the driving force.

Differences extended beyond administrative systems: the English regions are largely Protestant, while eight French regions are mostly Catholic, according to a 2012 US State Department report.

Cameroon’s English-speakers represent 20% of the population, according to the most recent census in 2005. Their marginalisation manifests itself in all spheres of life, from representation in politics to imbalances in regional development.

Cameroon’s ministers of defence, finance, education and foreign affairs are all French-speaking. The imbalance is reflected in the civil service’s hiring practices. The percentage of Francophone Cameroonians working as civil servants in [Anglophone] southern Cameroon could be as high as 90% of the total, according to a 2012 report by the Unrepresented Nations and Peoples Organisation, based in The Hague.

This asymmetry is manifested in development, too. One example is the under- development of the road network in the English-speaking south-west. “The lack of infra- structure development is evident when you consider that when traveling from [south- ern] Buea to [western] Mamfe, one has to travel through [the more central] Bamenda,” points out Sandra Sadack, a journalist for Green Vision, published by the Environment and Rural Development Foundation of Cameroon, an NGO. For this reason the economic potential of the region, rich in lumber and cocoa, remains unfulfilled.

Although 281 languages are spoken in Cameroon, it is officially a bilingual country. English and French are the two official national languages.

The disparities extend to further education. For example, Cameroon’s national vocational studies certificate is called the Certificat d’aptitude professionnelle (Professional Aptitude Certificate) or CAP. It is administered in French and has no English equivalent. This means that employment in technical fields such as electricity, textiles, plumbing and carpentry is difficult for those without a mastery of the French language.

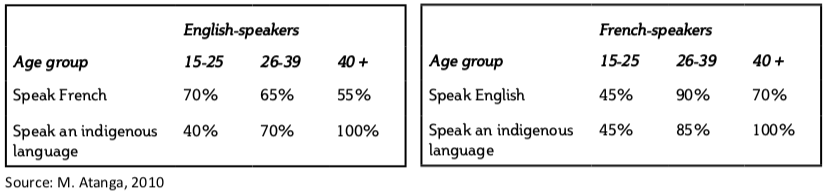

The linguistic and cultural divides inherited from colonialism remain important in Cameroon today. These walls, however, are crumbling because English is increasingly used as the language of international commerce.

“The increased presence of Francophones in [English-speaking] boarding schools is reflective of their sentiments towards the English language being the bridge toward greater employment,” says Dr Richard Talla, head of the history department at the University of Buea, the first English university in Cameroon. “There was a time when it was the Anglophones who were struggling in numbers to learn French. Now there has been a shift whereby it is the Francophones who are filling up the classrooms to learn English.”

Lillian Metogo is the director of a bilingual nursery and primary school in Bonaberi, a town in Cameroon’s French-speaking Littoral province. She echoes this sentiment. I think a time is coming when “one will not be able to differentiate between Anglophone and Francophone [Cameroonians] due to the increase of bilingual schools,” she says.

In Ms Metogo’s experience, Francophone parents are more supportive of their children learning English than English-speaking parents are of their children learning French. “[French-speaking parents] are looking at the bigger picture, which is that bilingualism opens the door for employment opportunities,” she says. “When multinational companies come to Cameroon and recruit, they want candidates who can speak English and French.”

Companies such as Euroil Ltd., the Cameroonian oil company, and AXA, a French insurance company, operate in predominantly English-speaking industries (banking, energy and oil, information technology, telecommunications and tourism) and require employees with a good com- mand of English, according to a 2010 study on the role of English skills in career advancement by Euromonitor International, a London-based market intelligence firm.

It is an interesting time to be an English-speaker in Cameroon. A language that once relegated its speakers to “second-class citizens” is now a highly sought-after commodity.

While divides are shrinking in commerce, French-speaking domination in the corridors of political power persists. Mr Biya’s highly centralised regime systematically denies English-speakers—and any other opposition group—access to government control, mostly through political appointments. For example, the president appoints the country’s ten regional governors and 30 out of 100 senators.

Mr Biya, 80 years old, has been in power for 31 years, making him one of Africa’s longest-serving leaders. He has chosen as his successor the French-speaking Marcel Niat Njifenji, president of the senate, ignoring English-speaking Prime Minister Philémon Yang, his official second-in-command.

This is a pattern in Cameroon, says Paul Abine Ayah of the opposition People’s Action Party. “It is not uncommon to find a Camerounese [sic] as head of department with a more qualified, more experienced, [English-speaking] southern Cameroonian as his subordinate,” he says. Even when a southern Cameroonian is in a position of power, as is the case with the prime minister, he commands no respect from his ministers. “The southern Cameroonian is at best only a figurehead.”

At the base of the large reunification monument in Buea is written: “Cameroon is United One and Indivisible”. If Cameroon is to live up to these words, it must address the system of “power by appointment” that marginalises English-speakers from politics. Unification is occurring from the bottom up; now it must happen from the top down, too. This is a lesson for leaders far beyond the borders of Cameroon.