Urban transport

The continent’s major cities need to address traffic congestion in a hurry

Africa’s largest cities are choking with traffic. In Egypt’s capital Cairo, for example, congestion costs the country $8 billion a year in lost productivity, additional fuel consumption and the impact of pollution, according to a 2012 World Bank study. The highways of Lagos, Nigeria, are backed up for hours every morning and afternoon, according to a 2013 study in the International Journal of Civil, Architectural, Structural and Construction Engineering. There is similar gridlock in Ethiopia’s capital Addis Ababa, Kinshasa in the Democratic Republic of Congo, Angola’s Luanda and Nairobi in Kenya.

High-capacity public transport systems such as subways, light rail transit (LRT), bus rapid transit (BRT) and modern tramways offer affordable and environmentally friendly solutions to the cross-continental crisis. But while some north African countries are moving to these more efficient modes, sub-Saharan states need to accelerate if they want to catch up.

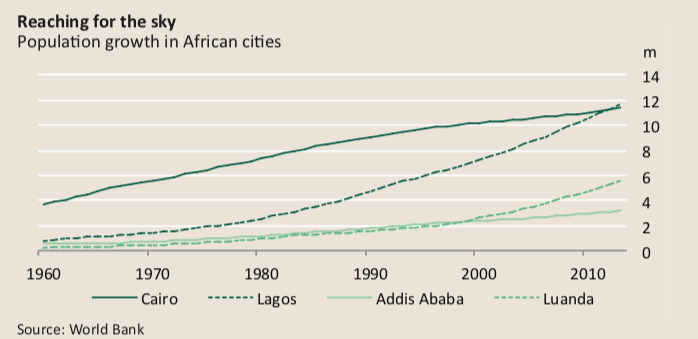

The population in African cities has skyrocketed in the past 50 years. For example, 762,000 people lived in Lagos in 1960, according to the World Bank. Today the population of the wider metropolitan area is estimated at 21m and forecast to reach 35m by 2025, according to Lagos city authorities. In 1960 Cairo was home to 3.7m people, according to the World Bank. Today 15.2m live in the city, according to the Demographia World Urban Areas 2014 report. Existing public transportation systems cannot cope with this growth.

The most popular form of public transport in most African cities is the minibus taxi because publicly run bus services are scarce, costly and inefficient, according to a 2009 World Bank study. The problem with minibus taxis is their limited capacity of 15 to 20 passengers each. Their proliferation poses many problems: including traffic con- gestion, air pollution and frequent traffic accidents, according to the study.

A standard bus system can carry 8,000 passengers per hour in a given direction, according to a 1994 report on public transport systems by the Swiss National Science Foundation. This comparative study showed that an electric tramway system can trans- port up to 20,000 people per hour, compared to the 30,000 carried by LRT and 50,000 by a subway system.

The study does not mention BRT, which combines the capacity and speed of a rail network with the flexibility and low cost of a bus system. The vaunted TransMilenio BRT system in Bogota, Colombia, for example, has recorded a maximum of 35,000 people per hour, according to a 2005 study by Colombian civil engineer Darío Guerrero.

The source and potential solutions to Africa’s traffic congestion lie in the continent’s late 19th century urban systems. Colonial governments introduced electric tram- ways in African cities such as Algiers and Oran in Algeria, Cairo, Lourenço Marques (now Maputo) in Mozambique, as well as Cape Town and Johannesburg, among other South African cities.

The tram networks of that era were designed mainly to serve the needs of the colonial administration, connecting the central administrative and business districts with upper class suburbs and ignoring the needs of poorer inhabitants.

During the mid-20th century’s era of independence, oil was cheap and the private motorcar proliferated. This led some African cities with efficient public transport systems to replace them with less efficient buses instead of modernising and expanding them. The last tramcar ran in Algiers in 1959, in Tunis in 1960. Apartheid South Africa discontinued its last trams in Johannesburg in 1961.

Egypt was an exception. It kept its established tram and light rail systems in Cairo and Alexandria and modernised them in the 1970s with Japanese-built cars. Like much Egyptian infrastructure, however, these systems are now in urgent need of re- juvenation after decades of neglect during the era of former dictator Hosni Mubarak. Most cars, tracks and overhead lines are run down.

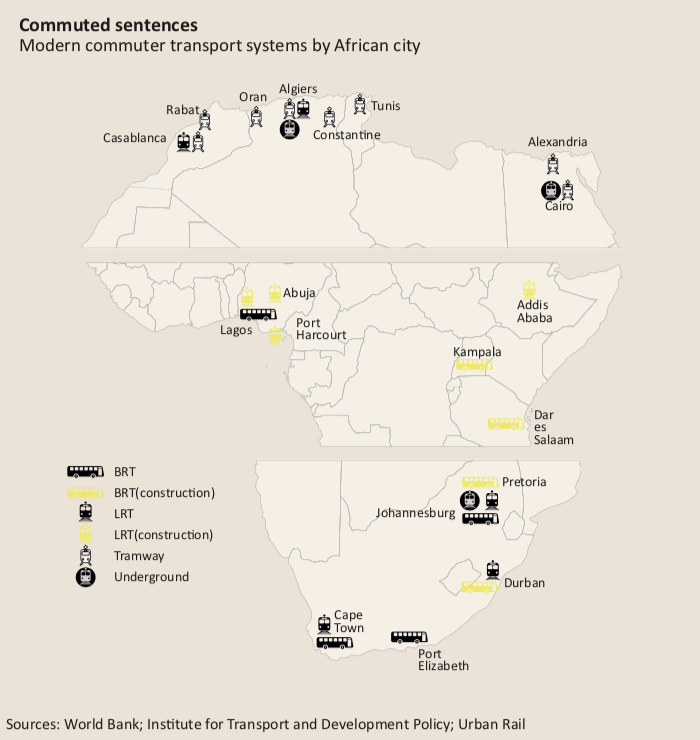

Some African cities, such as Cairo and Tunis, have recognised the need to adapt to new transport challenges by reviving other mass transport systems. Cairo, for in- stance, inaugurated Africa’s first underground subway system in 1987. Today the city boasts two subway routes, with a third route under construction. This limited network, however, is inadequate for a city of 15m inhabitants.

In 1985 Tunis introduced Africa’s first LRT, a hybrid of a subway and a tram- way. It was modelled on the successful Hannover Stadtbahn, one of Germany’s first LRT systems.

The light rail vehicles run along city streets like a tramway, without costly underground tunnels. Capacity is high: a two-car set can carry more than 500 passengers. Five routes were operating on an 80km network, according to a 2007 report by the Brussels Intercommunal Transport Company, which helped to develop this system.

Other African countries are following suit. Algeria launched an ambitious national transport plan in 2008. Modern tramway systems were inaugurated in Algiers, Oran and Constantine, together with a 9.5km subway line in Algiers between 2011 and 2013. Tramways are environmentally friendly because they are powered by electricity, which produces zero emissions on the spot and can be generated from renewable sources. In addition, they are far cheaper to build than subways. On average, the construction of one tramway kilometre costs only a tenth of one subway kilometre. Morocco introduced modern trams in Rabat in 2011, integrating the new lines and stations with the capital’s historic Islamic and French architecture. The government also built an LRT in Casablanca in 2012.

Some sub-Saharan African cities are slowly following suit. The Lagos Metropolitan Area Transport Authority is constructing a high-capacity LRT line between the neighbourhoods of Okokomaiko, Iddo and Marina. The routes will be isolated from car traffic, according to the authority, which hopes to open a first section in late 2014. Another LRT system is under construction in Abuja, Nigeria’s capital.

In Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, construction of a two-line LRT system, which includes tunnels and elevated sections, began in December 2011 and the first section should be completed by 2015.

In South Africa, cabinet approved a bus rapid transit programme in March 2007. BRT, which was pioneered in 1974 in Curitiba, Brazil, is characterised by segregated lanes, stations for getting on and off, the prepayment of fares and traffic signal priority, which automatically makes traffic lights turn green when the bus approaches a junction. Three BRT systems have been built in South Africa so far: in Johannesburg, Cape Town and Nelson Mandela Bay; others are under construction in Durban and Pretoria.

Johannesburg’s “Rea Vaya” (“we are moving” in township slang) has been operational for five years. Despite some opposition from minibus taxi operators unhappy about the competition, the system provides reliable and affordable transport to 100,000 passengers a day, according to President Jacob Zuma’s 2014 state of the nation address.

Two other sub-Saharan African cities are also building BRT systems: Dar es Salaam in Tanzania and Kampala in Uganda, according to a 2013 report by UN-Habitat, the United Nations human settlements agency.

While 400m Africans or 40% of the continent’s population live in cities, these figures are projected to reach 1.2 billion people or 58% by 2050, according to 2014 UN projections. Sitting in traffic instead of working, consuming more fuel because of extended travel times and the negative environmental impact because of increased fuel emissions are costly. A 2011 World Bank report estimated the annual cost of congestion in Cairo is 4% of Egypt’s GDP. This is four times the usual estimate of 1% of GDP as the cost of congestion in comparable large cities.

If African governments want to avoid the paralysing gridlock seen in Cairo, Lagos and Nairobi, which torments residents and restricts economic growth, they will need to fast track these transport solutions. Investment in customised mass transport systems would make African cities more competitive, ease business and improve the quality of life of all the continent’s urban residents.