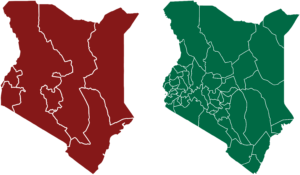

Kenya: central versus local

Two years after this east African nation transferred power to local counties, some governors want to amend the new constitution

Billow Hassan stands in the parking lot behind the hospital building in Mandera, the capital of Mandera County in northeastern Kenya. “Ten years ago there was one ambulance in the whole region,” says the 24-year-old community organiser. “When people got sick, they often had to walk miles to a clinic.” Now, he says, pointing to a row of vehicles parked against the fence, “the county has six ambulances, always on stand-by.” Mr Hassan credits the improvement to Kenya’s new devolved system of government, introduced in the 2010 constitution. While this new charter addressed other issues, including a bill of rights and land management, the most important transformation was the new power-sharing structure of government. The constitution replaced eight provincial administrations with 47 new counties after the March 2013 general election. The system sought greater decentralisation, with the central government sharing more power with local administrations.

Some, however, contend that the central government is not sharing funds as called for in the constitution, which allocates 15% of Kenya’s revenue to the counties and the rest to the national government. To rectify this wrong, Isaac Ruto, chairman of the council of governors, launched the Pesa Mashinani (“money to grassroots” in Swahili) petition last September. Led by Mr Ruto, governor of Bomet County in Kenya’s south-west, the campaign calls for a constitutional amendment to increase to 45% the proportion of revenue channelled to the counties. About 30 of 47 governors support this movement. This increase is needed “for the counties to realise their potential and for devolution to work,” Mr Ruto claims. The campaign is trying to collect 1m signatures of registered voters, a first step to holding a referendum to amend the constitution. After the elections board verifies the signatures, 24 of the 47 county assemblies would need to approve the petition for it to become a referendum bill.

If it passes at the local level, both houses of the national parliament must approve the bill with a simple majority. If parliament passes it, then the president must hold a referendum within 90 days. The petition has split the country in two, spurring fiery debates about revenue allocation. Some government officials, however, argue that the campaign’s organisers are less interested in the issues and more set on undermining the ruling Jubilee coalition. Jubilee’s Kipchumba Murkomen, senator for Elgeyo Marakwet County in western Kenya, points out that just two months before the launch of Pesa Mashinani, the opposition Coalition for Reform and Democracy (Cord) launched a campaign dubbed “Okoa Kenya” (Save Kenya) pushing for increased county allocations. But the governors’ Pesa Mashinani is a one-issue campaign focusing solely on raising county allocations while Cord’s crusade also addresses insecurity, ethnicity and other issues.

The governors have distanced themselves from Cord’s movement because they do not want to be dismissed as opposition sympathisers. The 15% stipulated in the constitution is merely a baseline figure, says Kinuthia Wamwangi, head of the transition authority, the body mandated to oversee the shift to a devolved system of government. The actual allocation to counties is, on average, more than 30%, he says, pointing to 2014 figures collected by the authority. Those who pushed for the new constitution—in the wake of the post-election violence of 2007 and 2008—saw devolution as the only way to end the historical marginalisation of the north-eastern provinces and the western Rift Valley. Wealth and power in the country have historically been concentrated in the capital, Nairobi, in the fertile south-west. Since the counties took effect in 2013, the increase in funds to previously marginalised areas has been significant. For example, in the 2013-14 financial year, the national government gave 7 billion Kenyan shillings ($76m) to Mandera County, where Mr Hassan lives.

This is more than the cumulative total the area received in the previous 50 years, according to the Commission on Revenue Allocation, a body established by the constitution to ensure equitable sharing of revenue between national and local administrations. Similar increases were found throughout the north-east: in Marsabit, Turkana and Wajir counties, among other previously marginalised areas. Mr Ruto does not dispute these increases, but argues that these allocations are still not nearly enough. The new constitution assigns management of health, local transport, early childhood education and public works to the counties. But the counties do not have enough money to cater for recurrent expenditure and development programmes in these areas, Mr Ruto argues. Some constitutional experts see the debate around stipulated proportions as a red herring.

“It would have been better to put more time in building the capacities of the counties and not just throwing money at them,” according to Winnie Mitullah, director of the Institute of Development Studies at the University of Nairobi. Ms Mitullah believes the challenges in applying devolution—including understaffing and misuse of resources in the local units—would have been reduced had the transition been done in stages: first setting up sound structures and then developing the skills of the county administrations. Mr Ruto disagrees. “After almost two years of implementing devolution, we have internalised the challenges and created better structures,” he says. “County governments have put in place systems to enhance people’s participation in resource allocation at the county level through budget debate forums. Citizens are able to hold their leaders accountable where they feel resources have been misused,” he adds.

Others argue that it is simply too early to amend the constitution. “We must first implement the constitution and afterwards see where things are turning out badly,” says Charles Nyachae, chairman of the official constitution implementation commission. “Then we might seek amendments.” Amending the constitution now, he says, would be “disastrous” because a loss of faith in the charter could threaten the country’s stability. The answer lies somewhere between the two camps. A 15% allocation is probably too little, even as a baseline figure. But changing the constitution will not solve the fundamental problem: mistrust between the county leaders and central government. To solve this problem, Mr Nyachae suggests adding yet another layer of government: a “middleman” institution that would resolve disputes between the government and the county authorities. A respected intra-governmental body, he says, would ease the tensions that threaten to derail what is, overall, a successful and functioning programme of devolution.

Raphael Obonyo is a public policy analyst. He’s served as a consultant with the UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs (UNDESA). An alumnus of Duke University, he has authored and co-authored numerous books, including Conversations about the Youth in Kenya (2015). He is a TEDx fellow and has won various awards.