INSIGHT: There is a correlation—if not the causation—between governance strength and citizen empowerment on the one hand, and economic prosperity on the other.

What is good governance? We frequently hear how important it is, partly because there’s so little of it on offer. In a nutshell, good governance is the transparent, accountable, and appropriate allocation of resources required to extend the public good and improve citizens’ lives.

In that vein, then, our vision at Good Governance Africa (GGA) is to improve citizens’ lives through strengthening governance across the continent. Together with our supporters, we envision a continent in which poverty is eradicated, corruption is destroyed, the rule of law is deeply embedded, and broad-based development is realised. Our mission is to influence policy formation and empower citizens to achieve this vision. We are guided in this by five unique differentiating values: independence, inclusiveness, integrity, courage, and credibility.

A major part of empowering citizens is to ensure not only that we harness the power of the vote but especially that we hold elected officials to account between elections. In a bumper election year across the continent, it’s crucial to guard against the global trend of ‘democratic backsliding’—a reversal of democratic gains manifested both in terms of declining voter turnout and rising authoritarianism.

Of the 59 countries classified as ‘authoritarian’ in the Economist Intelligence Unit’s (EIU) Democracy Index for 2022, Sub-Saharan Africa hosts 23 of them, followed by the Middle East and North Africa with 17. The number of ‘full democracies’ across the world increased from 21 in 2021 to 24 in 2022. But ‘hybrid regimes’ increased from 34 to 36. Hybrid regimes are those that display some elements or institutions typically associated with democracy, though these are often vehicles through which to advance authoritarian ends while providing a veneer of legitimacy for the regime (such as a rubber-stamp parliament). The hope is that we will see significant improvements in the 2023 index, which will be released next month. For instance, Zambia should at the very least be located in the ‘flawed democracy’ category instead of as a ‘hybrid’ regime.

In sub-Saharan Africa, the overall score was 4.24 in 2006. It gradually strengthened to a peak of 4.38 in 2015 and has declined to 4.14 in 2022. The global average over that time has also declined from 5.52 in 2006 to 5.29 in 2022. The good news is that South Africa scores relatively well at 7.05, third only to Mauritius and Botswana in the region.

For many, the idea of elections and the purported value of democracy are losing their shine. However, the evidence remains clear that democracies serve the objective of broad-based growth best in the long run. The best econometric models strongly support the hypothesis of a causal relationship between sustained democratic transitions and long-run economic growth. In other words, strengthening electoral democracy is likely to produce economic fruit.

In South Africa, such strengthening will take concerted effort. There are approximately 14 million unregistered young South African voters between the ages of 18 and 39. Since 2009, we have seen a steady decline in voter turnout. In that year, turnout was at 77.3%. By 2019, the figure had dropped to 66.05%. The ANC’s vote share has declined from 65.9% in 2009 to 57.5% in 2019. The EIU forecasts a victory at the polls this year of roughly 52%.

Many local pre-election polls suggest that the figure will drop below 50%, precipitating a need for coalition government at the national level. Not only is voter turnout declining, but 72% of respondents in the latest Afrobarometer Survey indicated that they would be willing to exchange the right to vote for improved material well-being. This is a shocking indictment of the current system and is strongly correlated with declining partisanship, the term describing the extent to which voters feel represented by any given political party.

This data indicates a need to energise voters to see the value of democracy, given rising levels of dissatisfaction with a lack of accountability. We have elections and expensive institutions like the Zondo Commission, but little obvious repercussion for those elites who commit wrongs at the expense of citizens. So, is it still worth having the vote, especially given the apparent success of countries like China and Rwanda that do not entertain democracy?

The short answer is yes. As Churchill famously stated in 1947, “‘Many forms of government have been tried, and will be tried in this world of sin and woe. No one pretends that democracy is perfect or all-wise. Indeed, it has been said that democracy is the worst form of government, except for all those other forms that have been tried from time to time.…’

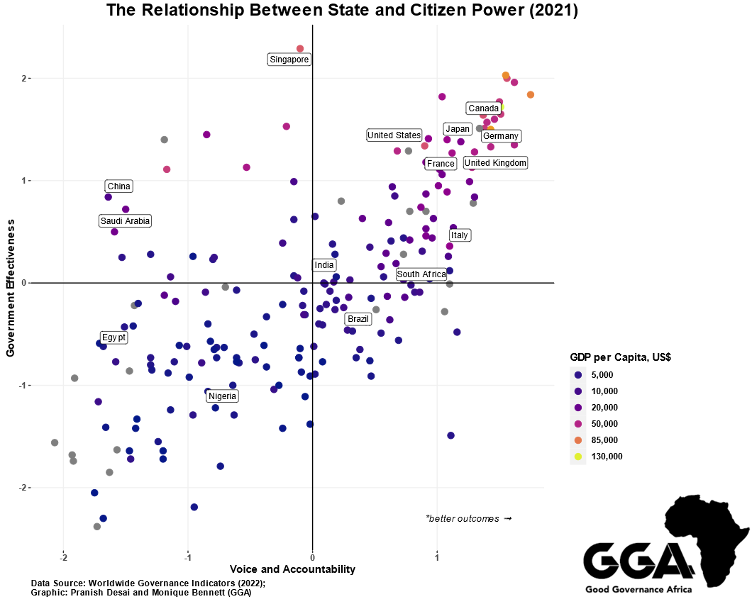

As the graph below indicates, you can see the correlation—if not the causation—between simultaneous governance strength (y-axis) and citizen empowerment (x-axis) on the one hand and economic prosperity on the other (represented by the colour bubbles). Countries that do best economically typically exhibit not only effective states but also a citizenry equipped and willing to hold their governments to account.

Built on decades of data and econometric regressions, our theory of change at GGA is derived from the work of economists Daron Acemoglu and James Robinson. They propose that state capability and citizen strength need to work arm in arm to produce a “narrow corridor”—a window in which economic dynamism can thrive and drive broad-based development. If you have an effective government at the expense of citizens’ ability to hold governments to account, you’re in for a hard landing. On that note, China is in real trouble, in large part because of citizen-suppressing policies and economic decisions that are proving unsustainable.

Driving government effectiveness and empowering citizens to hold their governments to account will produce the kind of broad-based development required to address youth unemployment and other drivers of democratic dissatisfaction. Government effectiveness is a function of a state’s regulatory quality, the traction of the rule of law, and its ability to control corruption. In turn, citizen strength is a function of the extent to which civil liberties such as freedoms of expression and association are respected, along with the quality of the electoral system.

We also have good evidence at the local level in South Africa, for instance, that well-governed municipalities are strongly correlated with higher voter turnout and lower levels of violent protest. However, we cannot focus exclusively on improving governance institutions to improve effective service delivery. We must also demonstrate to citizens that actively engaging government and holding it to account is a privilege worth fighting for. It is deeply concerning to see the levels of voter apathy rising in South Africa. One can fully understand it, though, and no one should ever be forced to vote.

However, the vote is one formidable expression of citizen voice that exists. Encouraging people to vote does not solve the problem of citizens feeling unrepresented by the major parties. But that is not an argument against democracy; it is an argument that we need to get better at equipping citizens to create their own platforms for engagement between elections and develop effective mechanisms of holding elected elites to account.

At GGA, we believe it is important to work both upstream—for instance, to effect policy changes that will result in a more politically accountable electoral framework—and downstream—for instance, to empower citizens to vote and develop an effective voice for engagement in between elections. In the end, government effectiveness at the expense of citizens’ voices is a recipe for long-run disaster, and citizen strength without a capable and effective state may produce chaos.

So, while good governance can empower citizens to deepen democracy, it is also true that empowering citizens through democratic institutions can deepen good governance. This is essentially a virtuous cycle in which state capability delivers services for citizens, and citizens ensure that the state is held to account at the ballot box, and between elections. This was the vision of our constitution, and it remains the responsibility of all of us to uphold its value as our primary guiding institution.

Dr Ross Harvey is a natural resource economist and policy analyst, and he has been dealing with governance issues in various forms across this sector since 2007. He has a PhD in economics from the University of Cape Town, and his thesis research focused on the political economy of oil and institutional development in Angola and Nigeria. While completing his PhD, Ross worked as a senior researcher on extractive industries and wildlife governance at the South African Institute of International Affairs (SAIIA), and in May 2019 became an independent conservation consultant. Ross’s task at GGA is to establish a non-renewable natural resources project (extractive industries) to ensure that the industry becomes genuinely sustainable and contributes to Africa achieving the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Ross was appointed Director of Research and Programmes at GGA in May 2020.