On 23 March last year, an air of tense anticipation enveloped Zimbabwe as citizens gathered around screens, their breaths held, awaiting the premiere of Al Jazeera’s highly anticipated documentary, The Gold Mafia: The Laundry Service. The buzz was palpable, and the documentary delivered. Unfolding over almost an hour, the film peeled back layers to reveal the festering underbelly of corruption that had taken root in the southern African nation. This revelation was not an isolated incident. The Willowgate, Draxgate, Nkandla, and Phala Phala farmgate scandals are etched in the collective memory of Zimbabweans and South Africans alike, serving as stark reminders of the pervasive corruption that plagues our societies.

In the weeks that followed, Al Jazeera rolled out episode after episode, each instalment laying bare more damning evidence of corruption reaching from people on the street to the highest echelons of power, implicating figures as prominent as the flamboyant prophet and government ambassador Eubert Angel, and even the Zimbabwean first family.

The narrative crossed borders, revealing the complicity of South African businessmen and officials. The documentary was a tour de force, featuring confessions captured on camera and audio that left viewers reeling. However, a friend’s triumphant proclamation that “This is an open and shut case, this time they are going down” was met with scepticism from me. “If you think anything is going to happen to any of those people, I suggest you don’t hold your breath, my friend, for you will suffocate,” I countered. The history of scandals like Willowgate and Nkandla, where accountability was elusive, informed my cynicism. While the Gold Mafia documentary stirred a maelstrom of emotions – sadness, fear, anger, and despair – I was painfully aware of the pattern: significant repercussions for those involved remained a rarity.

This sobering reality prompts a deeper inquiry, not merely into the acts of corruption themselves but into the psychological underpinnings that perpetuate this cycle. Delving into the minds and motives behind such actions, we must confront the uncomfortable truth: the battle against corruption is not solely in the hands of lawmakers and enforcers but rests on the shoulders of every individual.

Corruption casts a pervasive shadow, weaving through the fabric of daily life from the smallest of bribes to large-scale fraud. It transcends the clandestine exchanges of cash in dimly lit backrooms, infiltrating our everyday interactions: an unrecorded payment to a traffic officer, a secretive fee for a child’s school admission, the silent bypassing of customs. These seemingly innocuous acts, trivial and victimless on the surface, gradually erode our moral compass. The normalisation of such “petty” corruption wears away at the very foundations of society, transforming public services from societal pillars into hurdles to be circumvented. This insidious shift lays the groundwork for a systemic collapse, turning even the most routine of interactions into potential threats.

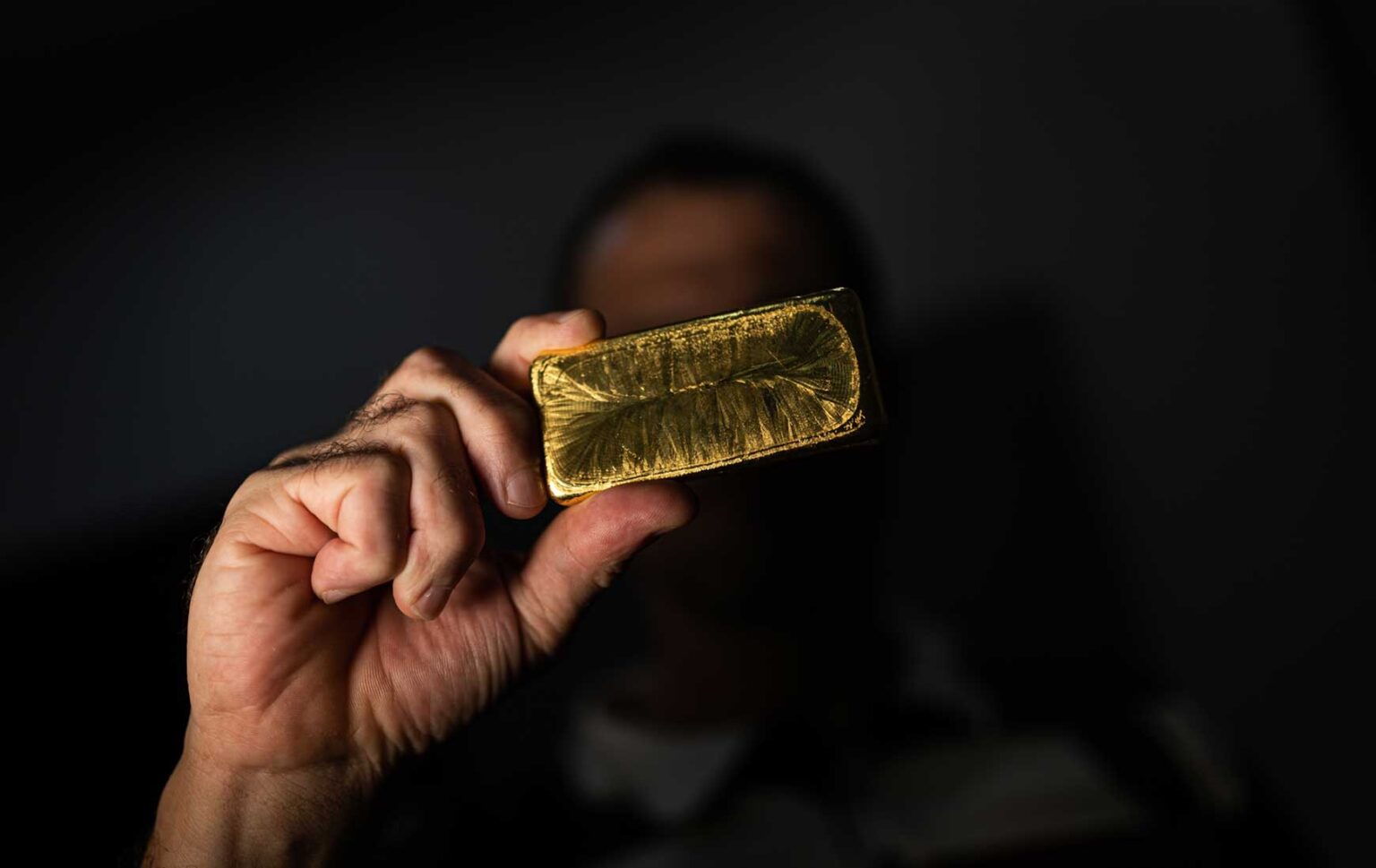

A young miner looks at an ore sample while searching for gold during a mine search and rescue operation in Kadoma, Mashonaland West Province, Zimbabwe, where more than 23 artisinal miners were trapped underground and feared dead in February 2019. Photo: Jekesai Njikizana/ AFP

The roots of corruption delve deep into the human psyche, challenging our perceptions of right and wrong. Philip Zimbardo’s observation that “good people can be induced into behaving in evil ways” highlights the blurred lines created by situational pressures and incentives. These forces exploit our cognitive biases, leading us down paths of rationalisation and moral ambiguity. In countries like Zimbabwe, Nigeria, Kenya, and Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), where bureaucratic systems tacitly endorse corruption for the sake of expediency, unethical practices become seen as necessary evils. This rationalisation process dulls our moral sensitivities, obscuring the collective harm our actions perpetuate and allowing corruption to seep into the very core of societal life.

Carl Jung’s concept of the “shadow self” posits that each of us harbours the capacity for both good and evil. This darker aspect, when unchecked by the counterbalances of compassion, ethics, and conscience, can drive us towards behaviours that prioritise personal gain over the common good. In the realm of corruption, traits such as narcissism, power-lust, status-seeking, and selfishness become not just personal failings but societal poisons.

The phenomenon of “positive illusions” compounds this issue, with many holding an inflated sense of their moral standing. This self-deception enables corrupt actions, as immediate rewards trump ethical considerations. In countries like Nigeria and Kenya, where corruption has become normalised, public outrage has plateaued, signalling a worrying desensitisation to ethical decay. A 2017 Chatham House study found that despite high levels of corruption in Nigeria, public outrage and demand for accountability remained low, indicating a normalisation of corrupt practices. Similarly, a 2019 Transparency International Kenya report revealed that while 71% of Kenyans believed corruption had increased, only 9% reported incidents of bribery, suggesting a resigned acceptance of the status quo.

Botswana, once hailed as a beacon of good governance, has seen a regression in its anti-corruption efforts since 2017. The 2021 Corruption Perceptions Index by Transparency International showed Botswana’s score rising from 61 in 2017 to 55 in 2021, indicating a decline in public perceptions of government integrity. This regression exemplifies how positive illusions can blind societies to their own backsliding, diminishing the impetus for reform.

The echo chamber of social proof and conformity amplifies corruption’s reach. The mantra “everyone is doing it” becomes a dangerous justification, seducing individuals into complicity with the corrupt status quo. Breaking this cycle demands a resurgence of moral courage, a willingness to challenge the norms and champion a new standard of integrity. As academic Dr Nkosana Moyo observed in 2018, “Zimbabweans are not fighting to change the system, they are fighting to be included in the system”. This poignant statement underscores the pervasive nature of corruption, where individuals often seek to benefit from the corrupt system rather than actively working to dismantle it.

Fear of loss – of status, power, or resources – can drive individuals towards corruption as a misguided means of self-preservation. As the DRC shows, outward “success” for the corrupt few hides inward devastation for the many. This mineral-rich country stands exploited, its potential and people sacrificed to satiate elite cartels and foreign enablers. As journalist Tim Burgis reveals in The Looting Machine, the fat bank accounts of Congolese politicians and their business cronies have come about through blood, fear, and the deprivation of fellow citizens.

The discourse around whistleblowing, establishing anti-corruption frameworks, and prosecuting the corrupt has been extensively covered and passionately argued by many before me. My aim is not to echo these points but to explore the small yet significant ways we can contribute to eradicating this pervasive scourge. Understanding the psychology of corruption highlights the vital role of personal agency in this battle. Although corruption may be deeply ingrained within structures, the decision to engage or resist begins with the individual. Systemic change requires recognising our power of choice: to either accept the status quo or courageously forge a path grounded in integrity. As the Ethiopian proverb goes, “When spiders unite, they can tie up a lion.”

This journey starts with self-awareness, urging us to examine our motives, incentives, and ethical blind spots that might unconsciously bias our decisions. A 2015 study by Sezer, Gino, and Bazerman, found that individuals who were prompted to think about their ethical blind spots were less likely to engage in unethical behaviour compared to those who weren’t given such prompts. The authors suggest that “by acknowledging our susceptibility to ethical blind spots, we can better avoid unethical decisions”.

True transformation goes beyond legal measures, aiming to reshape mindsets and cultural norms. Cultivating self-knowledge protects against the sense of entitlement and “positive illusions” that undermine our moral integrity. Education, both formal and informal, is crucial in instilling ethical decision-making skills and civic values from an early age. As Barbara Ritter pointed out in her research paper ‘Can Business Ethics Be Trained? A Study of the Ethical Decision-Making Process in Business Students’, “Students who have had ethics training are more likely to recognise and less likely to engage in unethical practices.”

However, maintaining integrity amid moral decay requires more than introspection; it demands moral courage. This involves challenging normalised corrupt practices, upholding values despite social pressures, and risking backlash to expose wrongdoing. While the path of least resistance might lead to complicity and silence, individual bravery can initiate a cultural shift towards prioritising ethics over corruption. An Igbo proverb highlights this: “When the mother cow chews the cud, the baby cow watches intently.” Our actions serve as a model for the next generation, who will either emulate our ethical behaviour or tread the path of corruption.

Open discussion about corruption and its psychological justifications clarifies how individuals rationalise unethical actions. Moral courage and ethics training, delivered through various platforms, are key to empowering officials and citizens to combat corruption. Government agencies like Nigeria’s Independent Corrupt Practices and Other Related Offences Commission (ICPC) and Kenya’s Ethics and Anti-Corruption Commission (EACC), along with professional associations such as the Association of Certified Fraud Examiners (ACFE), can provide workshops, seminars, and resources. Private sector companies can incorporate ethics training into employee development programmes. Grassroots activism and civic engagement, exemplified by Nigeria’s Integrity Crusaders and the Accountability Lab’s innovative “Integrity Idol” and “Citizen Helpdesks”, provide platforms for monitoring governance, reporting corruption, and advocating for transparency. By supporting these initiatives, we foster a culture of integrity and empower individuals to take a stand against corruption in their communities.

By intertwining daily ethical decisions with collective action, we have the power to dismantle the complex web of corruption that has entangled our societies. Through consistent efforts, we can erode entrenched networks of corruption, paving the way for a future where integrity and justice are foundational. This journey is long and challenging, but with each step towards righteousness and every act of defiance against corruption, we move closer to a world where ethical governance and societal trust prevail.

Adio-Adet Dinika is a writer, researcher and affiliated PhD Fellow at the Bremen International Graduate School of Social Science (BIGSSS). His areas of interest are Digitalisation and the Future of Work. He has published opinion pieces on Digitalisation and socio-economic development in several print and online publications, and his first unpublished novel, They like us dead, was long listed for the 2021 James Currey Prize for African Literature. He is currently based in Bremen, Germany.