Disinformation has proven deadly for many Africans

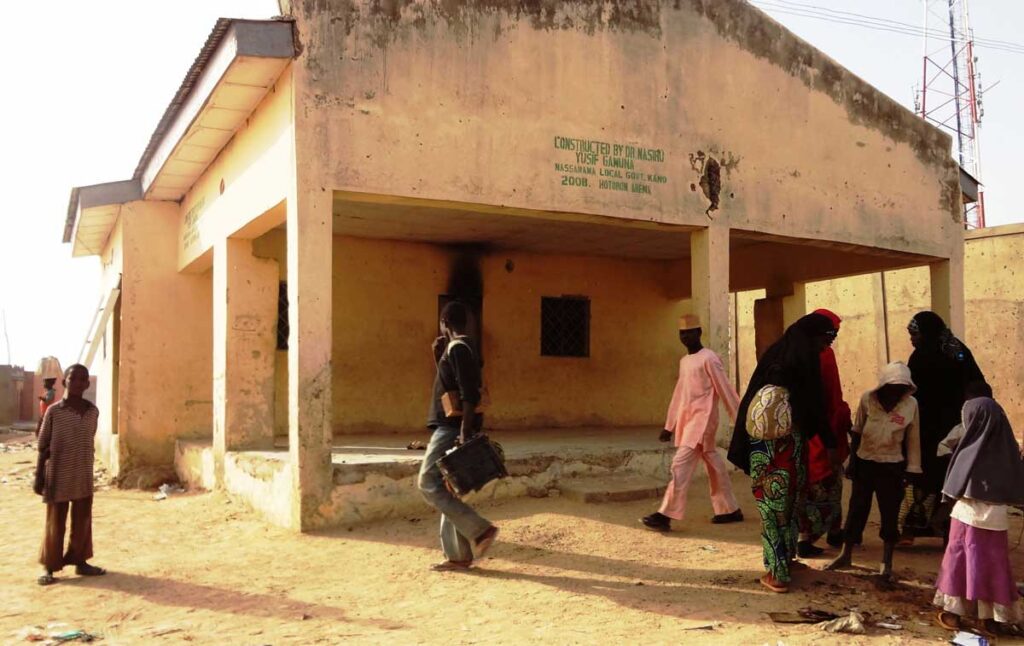

In February 2013, gunmen believed to have been members of the terror group Boko Haram shot dead nine female health workers outside two clinics in Kano state, northern Nigeria, where the women were preparing to provide polio inoculations. The killings occurred a full decade after the religious and political leaders of Kano, Zamfara, and Kaduna states urged parents not to allow their children to be vaccinated against the debilitating poliovirus.

Their opposition stemmed from a fatwa, or legal ruling, by Datti Ahmed, a Kano-based physician heading a prominent Muslim group, the Supreme Council for Sharia in Nigeria, who stated that polio vaccines were to be avoided as they were “corrupted and tainted by evildoers from America and their western allies … We believe that modern-day Hitlers have deliberately adulterated the oral polio vaccines with anti-fertility drugs and viruses that are known to cause HIV and AIDS.”

As a result, there was a resurgence of the poliovirus in Nigeria, where cases increased five-fold over 2002-2006, whereas it has been all but eliminated in the rest of the world, and quickly spread beyond Nigeria. It took health authorities until 2008 to regain control over the virus, as Sani-Gwarzo Nasir of Nigeria’s Federal Ministry of Health and colleagues said in a 2014 report, by getting the Sultan of Sokoto, Sa‘adu Abubakar, historically the most venerable Muslim ruler in Nigeria, to support a polio education roadshow based on convincing local imams and chieftains of the necessity to combat the disease.

However, many instances of so-called “fake news” – whether mistaken misinformation, deliberate disinformation, or outright propaganda – inflicted on communities across Africa in recent years, have proven far more dangerous to public safety. But, as with the health sector in Nigeria, many different communities of interest are fighting back.

The very colonisation of Africa, carved up by the imperialist powers at the Berlin Conference of 1884-5, was driven by massive and sustained false information campaigns: that Africans were primitive “savages” in need of European enlightenment, or simply that much of the land was terra nullius, a rich landscape with no indigenous sovereignty and thus ripe for the taking.

While nowhere near as far-reaching in its impact and implications, some recent examples of false information peddled in different regions of the continent have caused untold damage. This has mostly centred on public panic around pandemics such as HIV/Aids, Ebola, and Covid-19, because such health crises provoke a sense of extreme vulnerability in communities that are swamped with difficult-to-understand scientific information, and so often look towards unsubstantiated explanations and quack solutions.

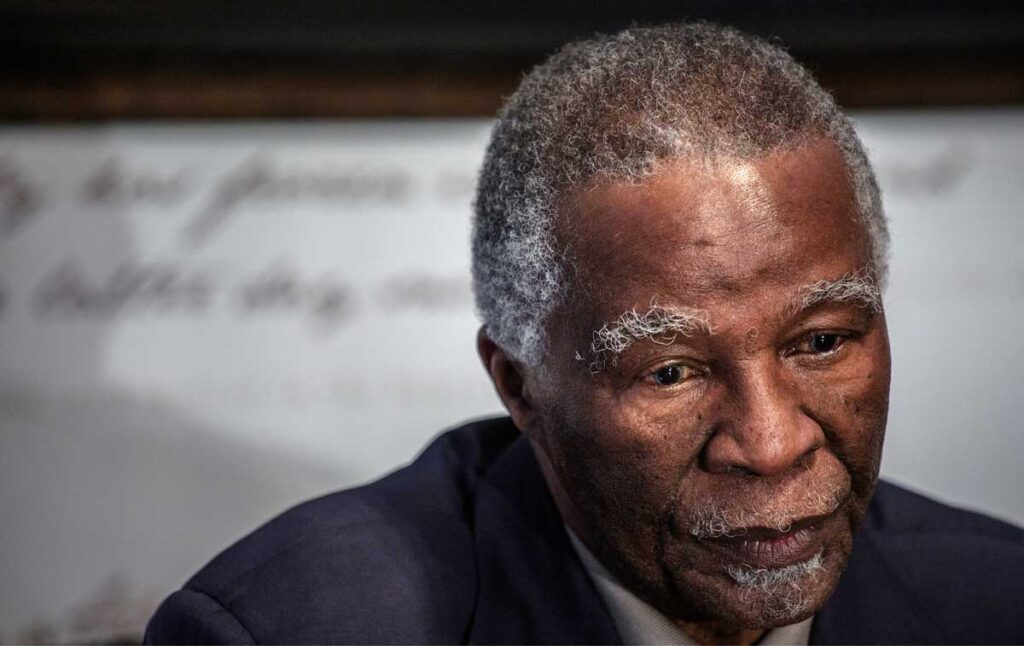

Probably the most notorious example of public misinformation spread about HIV/Aids was that assiduously driven by South Africa’s President Thabo Mbeki during his 1999-2008 presidency.

Influenced by dissidents who disputed the global scientific consensus that the virus did indeed cause the killer immunodeficiency syndrome, Mbeki repeatedly publicly expressed his deep distrust of “western” science and big pharma, claiming anti-retroviral drugs (ARVs) were poisonous and had been designed by whites to harm blacks, and that Aids was a disease of poverty that could be combated simply by better nutrition.

As a result, he instituted policies that for years denied ARVs to Aids patients and withdrew support from clinics using them to prevent mother-to-child transmission, instead backing a shady locally developed drug called Virodene, based on a toxic industrial solvent, against the advice of the Medicines Control Council.

Two communities combined to successfully challenge Mbeki’s Aids scepticism: community activists such as the Treatment Action Campaign, which took the government to the Constitutional Court, compelling it to distribute ARVs, and scientists, 5,000 of whom in 2006 issued the Durban Declaration that strongly affirmed the consensus on the cause of Aids. This forced a reluctant reversal of ARV policy in October 2006.

A study by a researcher into Aids denialism, Prof Nicoli Nattrass of the University of Cape Town, concluded: “Demographic modelling suggests that if the national government had used ARVs for prevention and treatment at the same rate as the [province of the] Western Cape (which defied national policy on ARVs), then about 171,000 HIV infections and 343,000 deaths could have been prevented between 1999 and 2007.”

In the case of an Ebola virus outbreak in West Africa that caused at least 11,323 deaths over 2013-2016, misinformation spread via social media had similarly disastrous consequences. A study by Melissa Roy of the University of Ottawa and others in 2019 into who affected communities blamed for the crisis showed that “emotional” social media users blamed, in descending order: governments for poor virus containment; neighbouring “others” and migrants for starting and transmitting the virus; the media for fearmongering; and global elites and big pharma for supposedly creating the virus to kill Africans.

Fact-checking non-profit organisation Africa Check was founded at Wits University’s journalism department in Johannesburg in 2012 as the development arm of the international news agency AFP and now has offices in Dakar, Lagos, and Nairobi. It warned during the pandemic that wildfire social media claims such as that Ebola was airborne were false, and that the virus had no cure, so bathing in salt water or ingesting “nano-silver” would have no effect.

That Africa Check, which aims to foster “accuracy and honesty in public debate”, was an outgrowth of journalism is no surprise, as legacy and new media are the nexus from which most widespread false rumour distribution radiates out into public healthcare, religion, the economy, and politics. Also, journalists themselves are often key victims (and perpetrators) of mis/disinformation campaigns; so, on that score the organisation has trained 4,500 journalists on verification techniques.

The issue has become so pressing that Africa Check, the continent’s first fact-checking organisation and author of more than 1,300 reports in English and French, has seeded a proliferation of similar outfits abroad, 20 of them working together in the Africa Facts network, founded in November 2017 and covering most of sub-Saharan Africa.

Since false information causes such widespread damage in many fields, the USAID-funded pro-democracy Consortium for Elections and Political Process Strengthening (CEPPS) now has a lengthy directory of responses across various African communities to mis/disinformation. That includes organisations that verify health issues such as BBC News Africa’s Covid-19 MisinfoHub resource, correcting what it terms the “infodemic” of fake news on the coronavirus pandemic. Then there are those like Fake Watch Africa in Malawi, which monitors politicians’ wild claims during election season.

Some are naturally located within investigative journalism, such as the African Network of Centres for Investigative Reporting (ANCIR), which has an iLab project that “uses forensic data science techniques to expose the networks that disseminate and amplify misinformation, disinformation, and toxic content (such as hate speech or extremism) with a special focus on coordinated inauthentic behaviour and other influence/information operations.”

Some are based within high-tech communities, such as Code for Africa, a non-profit based in Nairobi, which runs an AI/machine learning initiative called Civic Signal, “using large-scale media monitoring to map the content/creator landscape and underlying business models for disinformation profiteers.” It uses “language processing tools to analyse the underlying narratives that shape public discourse and perceptions and make the public vulnerable to disinformation and extremism.”

Code for Africa has its own continental network, the African Fact-Checking Alliance (AFCA), which brings together media and civil society organisations that work to counter misinformation, “[supporting] fact-checking missions to debunk dangerous content, including conspiracy theories and misinformation.”

Some verification organisations work within the developmental NGO space, such as the African Academy for Open-Source Investigations (AAOSI), an initiative of the International Centre for Journalists (ICFJ), “supporting media and NGOs in Ghana, Kenya, Nigeria, and Senegal to identify and address problematic behaviour in the information space”. As with Africa Check and Code for Africa, the ICFJ initiative provides training, mentorship, and organisational support.

For communities of interest, shooting down false information in which “disinformation profiteers” have invested so much is of course not without its perils, especially when they are political extremists, fly-by-night businessmen who employ mercenaries, or snake-oil “bishops” with tens of thousands of irrationalist followers easily roused to anger. For example, ersatz populist churches that use their tax-exempt status and cash-based operations to launder money for Latin American cocaine cartels penetrating Africa are notoriously litigious against exposés of the realities of their sources of funding.

And groups that undertake holding others to account have to themselves be rigorous in how they deal with statistics and interpret data. Africa Check, for example, was challenged in 2018 by the liberal Institute of Race Relations on the soundness of its interpretation of controversial farm murder statistics in South Africa.

An internal Africa Check survey on its 20-organisation Africa Facts network in 2021, by Charlotte Xiaou Wu, noted significant challenges to outfits monitoring accuracy in reporting in all fields, foremost among which was the need to “work hard to communicate their nonpartisanship and independence, both intellectual and financial, to build their audiences’ trust”.

As one of Wu’s interviewees put it, “Staking out a role as arbiter in a highly disunified space and demonstrating professional neutrality builds the trust needed for organisations to reach audiences across the political divide.” Against a backdrop of the difficulty of fund-raising and sustainability in a contracted post-Covid economy, it is vital that fact-checking organisation openly declare their sources of funding and assiduously avoid the merest hint of political inflections in their reporting.

And yet her interviewees noted “that government interference was one of the main challenges in media reporting in [their] countries… Many countries on the continent are younger democracies with less established political and health systems, where securing the quality of information and public debate is felt to be of existential significance.”

The quality and accessibility of data was vital to verification, they told Wu. Even supposedly open, public information was often impossible to find, while the legwork involved in assessing data, already a labour-intensive yet time-sensitive task, was more extensive than that required in developed countries, where data systems were more complete and responsive.

Wu reported that government internet shutdowns to suppress dissent exacerbated Africa’s low digital penetration and data literacy, creating conditions where verification organisations were forced to adopt additional strategies to reach communities that would otherwise not be exposed to corrective narratives. Congo Check, for example, she said, ran public roadshows to offline communities on key disputed facts in their society.

An equally huge challenge was the sheer diversity of languages across Africa: “In Nigeria, for example, more than 500 languages are spoken. This can present a challenging dynamic,” Wu writes, citing an interviewee warning that if false information was published in one of the dominant, or official languages of the country, where it can be adequately combated by fact-checkers, it would still likely resurface “in local languages with no counter-narrative, and spread quickly…” Communicating counter-narratives, therefore, had to take place on multiple platforms and in many languages.

Wu drew attention to a blog by Check’s Kenya editor, Alphonce Shiundu, that pointed out “false information can be particularly difficult to counter when it circulates in societies with shared ‘experiential and communal worldviews’, which give readers a perception if its ‘innate accuracy’.” These types of communal echo-chambers were amplified, for example, by private WhatsApp groups, a popular source of information in many African countries, run by community or religious organisations.

Political interference via large-scale propaganda campaigns on social media by foreign powers such as France, the United States, China, Russia, or the United Arab Emirates can also have immense impact. For instance, the Russian state-linked mercenary Africa Corps’ (formerly the Wagner Group) troll farm, the Internet Research Agency, pilloried the West and promoted Russian interests on West Africa social media, which created the zeitgeist, which since 2021 has toppled three pro-western governments in Mali, Burkina Faso, and Niger.

Thus, with even established western democracies revealed to be vulnerable to rapidly evolving and spreading disinformation campaigns, verification organisations must repeatedly upskill and continually identify the many gaps in public-interest reporting – especially as it affects people’s services and livelihoods.

Michael Schmidt is a Johannesburg-based investigative journalist who has worked in 49 countries on six continents. His main focus areas as an Africa correspondent for leading mainstream journals are emerging and high-end technologies, political developments, conflict resolution and transitional justice, and on the continent’s maritime and littoral spaces.