Nigeria: banks and other barriers to business

High interest rates are strangling small businesses in Africa’s largest economy

The elation in Nigeria at the news, released last April, that the country had overtaken South Africa as the continent’s largest economy, was largely confined to government circles.

Many Nigerians have refused to get caught up in the excitement. Abiodun Ayinde, 69, who owns a small waste management company in Lagos, Nigeria’s largest city and economic capital, is one.

Mr Ayinde does not care about the rivalry between Nigeria and South Africa. Topmost in his mind is the quest that has given him sleepless nights in the last five years: Mr Ayinde’s clientele is growing and his expanding business urgently requires more staff and one more mobile waste compactor.

“Business is not doing badly at all,” he says. “But the problem I have is that I am unable to raise funds to further expand the business. I need to buy a compactor and I also want to employ more hands.”

On paper, there are several funding options available to a Nigerian business person who wants to set up a new business or expand an existing one. The country has 21 commercial and two specialised government banks set up to fund large-scale industry projects, as well as 871 microfinance firms authorised to lend to small-scale businesses and entrepreneurs.

But in practice it is not easy for small companies to secure loans. Mr Ayinde’s efforts to raise a 2m naira ($12,500) bank loan to buy a used waste compactor and hire new staff have been unsuccessful. His is a typical story.

Most Nigerian entrepreneurs and small-scale businessmen do not start companies by borrowing from a bank. Official numbers on bank borrowing are lacking, but from years of talking to small business owners, this writer has learned that most Nigerian entrepreneurs turn to banks only when they need funds to expand an already successful business.

This is because banks and microfinance institutions charge prohibitively high interest rates and attach onerous requirements to loans.

Funding challenges are spanners in the works of many small businesses in Nigeria, according to Femi Egbesola, the president of the Association of Small Business Owners of Nigeria, a trade group. “Most of the financial institutions are requesting for conditions that are difficult for small companies to meet, [especially] collateral,” he told Leadership, a Nigerian daily, last April. “The banks charge about 27% interest rate per year and everybody is complaining that it is on the high side.”

Some Nigerians question why interest rates have remained high despite a recent fall in the country’s inflation. A bank “must be a commercially viable enterprise, but why must they charge 20%?” asked Ngozi Okonjo-Iweala, Nigeria’s finance minister. Inflation in the first eight months of 2013 diminished from 12% in January to 8.7% in August, she added, “meaning interest rates can also go down”. As of March 2014, Nigeria’s inflation rate was 7.8%, according to the national statistics bureau.

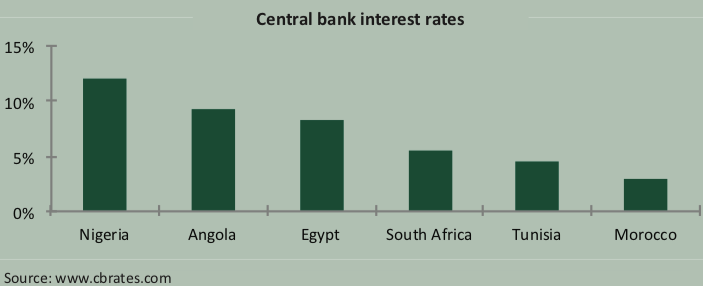

Commercial banks borrow from the Central Bank of Nigeria (CBN), which offers money to banks at a rate called the monetary policy rate (MPR). The CBN considers the country’s prevalent inflation rate while setting the MPR. The idea is to help banks lend to businesses at non-prohibitive rates. Figures from www.cbrates.com, a website that compiles world interest rates, show that Nigeria’s interest rate is one of the highest of Africa’s large economies. Nigeria’s current MPR of 12% is higher than the prevailing rates of 3% in Morocco, 4.5% in Tunisia, 5.5% in South Africa, 8.25% in Egypt and 9.25% in Angola.

Trade groups, such as the Lagos-based Manufacturers Association of Nigeria (MAN), have campaigned for lower rates for decades. The organisation’s 2013 report claimed that some Nigerian banks are charging borrowers as much as 35% on loans, a rate so high that businesses cannot survive. “In the last ten years, interest rates charged MAN members by banks have been at an average of 19.9% for most of the manufacturing sub-sectors,” according to the report.

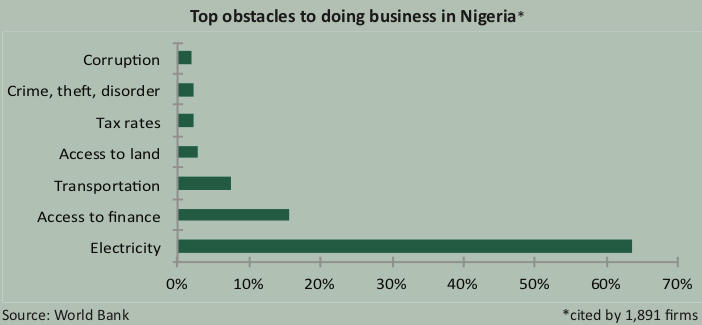

These high rates are just one facet of Nigeria’s crippling commercial environment. The World Bank’s 2014 “Ease of Doing Business” index places Nigeria at a lowly 147 of 183 countries. Many of the problems stem from Nigeria’s broken infrastructure. Entrepreneurs have to generate electricity from private generators, dig industrial boreholes to ensure a reliable water supply, and must also pay private security companies to secure premises and assets.

The US-based Omidyar Network, a philanthropic investment firm started by eBay founder Pierre Omidyar, released a study in 2013 on entrepreneurship in six African countries: Ethiopia, Ghana, Kenya, Nigeria, South Africa and Tanzania. Nigerian entrepreneurs lament that “inconsistent infrastructure electricity supply across the country has resulted in backup generators forming a key part of any business’s assets, albeit at a significant additional operational expense,” the report noted. “Nigerian respondents cited access to finance as a key challenge for starting and growing small businesses. In particular, the requirements for obtaining capital are prohibitive.”

Collateral of up to 120% is often required for debt financing, according to the interviews with the Nigerian participants in the Omidyar study. Collateral is high because banks fear that borrowers may default. As a result, 67% of respondents believe that bank lending policies for newer companies are more challenging than for well- established firms.

Bank executives, however, argue that high interest rates are forced on them by Nigeria’s challenging business environment. “I also want a lower rate,” said Philips Oduoza, the managing director of one of Nigeria’s biggest lenders, the United Bank for Africa (UBA), at a meeting with newspaper editors last January. “But when you look at it, you find that banks are an integral part of the economy. One of the reasons why [the] interest rate is very high in Nigeria is because of the infrastructure challenge,” he said.

Banks, like other businesses in Nigeria, pay a high price for the country’s infra- structure deficiencies, he added. For example, UBA has to generate the electricity that it uses at its headquarters and in its branches, Mr Oduoza explained. “UBA has about four generators at its head office that run simultaneously. It’s a mini-power station. Diesel consumption alone is extremely high. This is one of the reasons [the] interest rate is very high.”

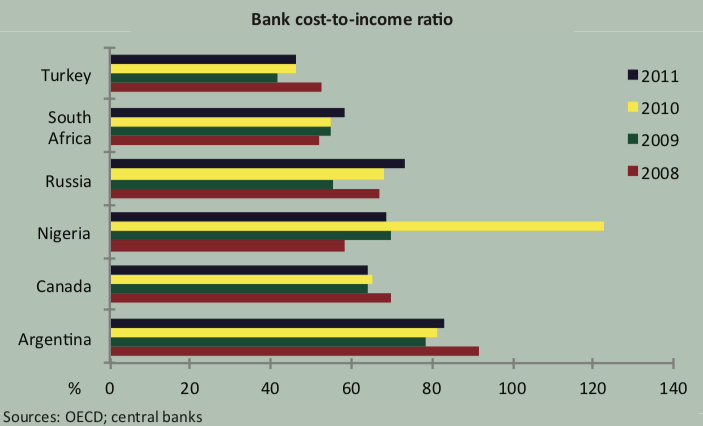

The way forward, according to Mr Oduoza, is for government to fix Nigeria’s infrastructure problems. “If you compare the financials of the Nigerian banks with those of other emerging and frontier markets, the cost-to-income ratio [a rough guide to how good a bank is at reining in costs] of Nigerian banks is in the 60s,” he said. “Some extreme ones are in the 70s. In all the other emerging markets like Turkey, Malaysia, India, etc, their cost-to-income ratios are in the 40s. So if we are able to deal with all these cost elements, I can tell you that the interest rate can come down to a single digit.”

Nigeria’s suspended central bank chief, Lamido Sanusi, agrees that the business environment and the country’s high interest rate are linked. Mr Sanusi, however, looks at the same problem from a different angle.

“It is not about moving the interest rate down or up. Most of the small- and medium-scale enterprises (SMEs) that do not have access to credit do not have access to credit because the environment does not allow businesses to thrive,” Mr Sanusi said during a public session with federal legislators in July 2013.

“How low do you have to bring down interest rates for banks to lend to a manufacturer that does not have power, or for a bank to lend to a company that operates in an environment that does not have security, or where there is no infrastructure?” he asked. “At what rate of interest would a bank loan to a tomato farmer who is going to lose 50% of his output between the farm and the market because there is no investment in storage facilities or cold rooms? These problems are infrastructure.”

Is there any government plan to fix infrastructure in Nigeria? Yes, a grand plan: the Nigerian Infrastructure Master Plan, projected to cost $2.9 trillion and last 20 years. But many Nigerians, such as Mr Ayinde, are not hopeful that it will yield immediate benefits. The country’s infrastructure has fallen into disrepair, he complains, because successive governments rarely keep promises to overhaul the system.

[author] [author_image timthumb=’on’][/author_image] [author_info]Adeyeye Joseph is the editor of The Punch, Nigeria’s biggest daily newspaper. He won the Nigerian Media Merit Award for editor of the year in 2011 and 2012 and newspaper columnist of the year in 2011. [/author_info] [/author]