Nigeria’s All Progressive Congress: high hopes or fading dreams?

The creation of Nigeria’s first credible opposition party met with great excitement in 2013. Will it maintain its momentum?

Nigeria is a political paradox: a multi-party democracy that has been led by just one party since it transitioned from military rule in 1999. For 15 years, no opposition has come close to challenging the dominance of the People’s Democratic Party (PDP). Not at least, until the All Progressive Congress (APC) emerged last year as the first credible opponent in the history of this civilian rule. Suddenly, the game seemed to have changed.

The APC was created when four opposition parties—the Action Congress of Nigeria (ACN), the All Nigeria People’s Party (ANPP), the All Progressive Grand Alliance (APGA) and the Congress for Progressive Change (CPC)—merged in February 2013.

The news of their unification met with great excitement. This was not the first effort at amalgamation. But in the past, mergers between minor, regional opposition parties were tabled at the last minute and invariably crumbled under pressure from in-fighting and competing political or ethnic interests.

By seeing the merger through, the APC broke new ground.Why the resolve? “The past attempts were half-hearted,” APC’s national publicity secretary Lai Mohammed told Africa in Fact. Now it is different, he said. “This time it was clear to the leadership of all the parties that the only way to survive was a merger. As long as they remained small, regional parties it would be easy for the PDP to make mincemeat of them,” he explained. “So they started early, and each party went with no conditionalities.”

The result is the first opposition party with potential to appeal to communities and ethnicities across the country. This, Mr Mohammed declared, is history in the making: “The first time in the history of elections in Nigeria that a ruling party will go into elections with a truly national, broad-based opposition which can really pose a challenge.”

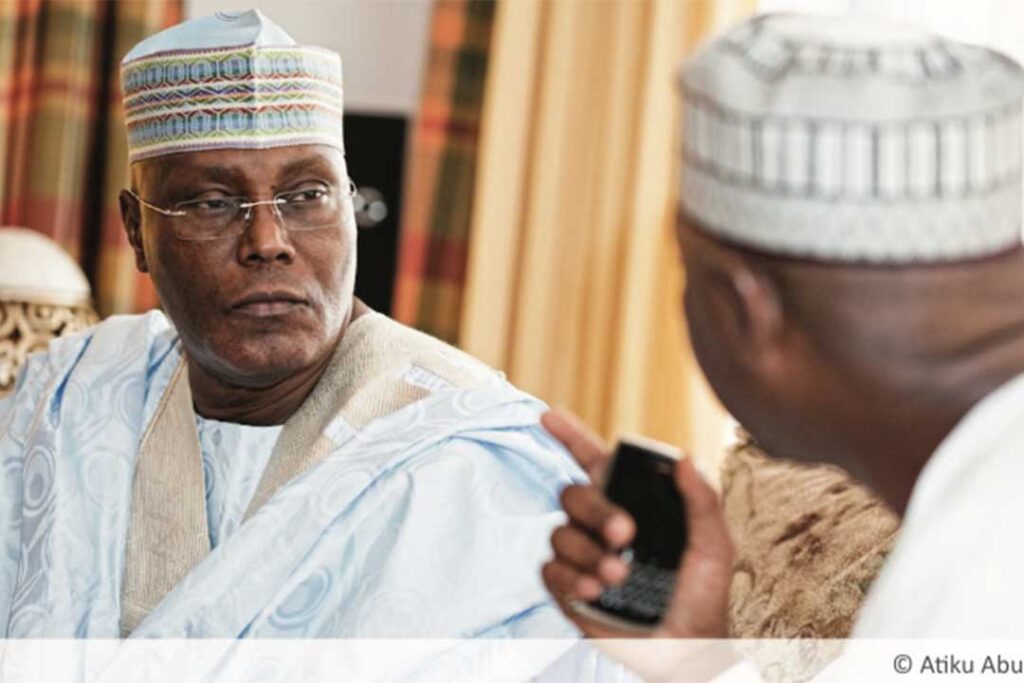

Since the new party’s formation, the PDP has had plenty of worries. Shortly after the APC was born, five ruling party governors defected to the new opposition. In February 2014 it won a major asset when Atiku Abubakar, a former vice-president, joined its ranks.

Increasing signs have emerged that the PDP’s popularity is diminishing. President Goodluck Jonathan won just under 59% of votes in the 2011 elections, down from the 70% taken by his predecessor, the late Umaru Yar’Adua, in 2007. Over that time, the ruling party’s strength in both the Senate and House of Representatives decreased. And according to Mr Mohammed, a2013 APC survey found that 70% of Nigerians were unhappy with the PDP leadership.

This is unsurprising. Despite vast oil wealth, a larger proportion of Nigerians are poorer today than a decade ago. According to the Nigerian Bureau of Statistics’ most recent figures, 61% of the population lived on a dollar a day or less in 2012; an increase of almost 10% since the last measurement was taken in 2004. More recently, the World Bank noted in 2013 that“poverty reduction and job creation have not kept pace with population growth, implying that the number of underemployed and impoverished Nigerians continues to grow.” Crumbling infrastructure, industrial scale oil theft, endless corruption scandals, and a worsening insurgency in Nigeria’s north-east have further undermined the leadership’s credibility.

The APC has tried to position itself as the harbinger of a new beginning. “At no time in our national life has radical change become more urgent,” Tom Ikimi, chairman of the APC merger committee, said at the party’s inauguration last year. It would offer “our beleaguered people a recipe for peace and prosperity”, he added.

That optimism, though, has been tempered in recent months. Momentum seems to be fading. The PDP has reclaimed control of Adamawa and Ekiti, states in Nigeria’s north-east and south-west respectively. At the same time, several high-ranking APC politicians (including Nuhu Ribadu, the influential former head of the Economic and Financial Crimes Commission) have returned to government ranks.

“While the APC appeared to be moving ahead earlier in the year…the past two months have seen APC members defect back to PDP amid allegations that the ruling party has used bribes and political favours to entice their return,” explained Sarah Tzinieris, principal Africa analyst at Maplecroft, a risk advisory company. She said that to-ing and fro-ing has increased political instability in the nation of more than 170m people.

The APC faces further challenges ahead. The two rival parties have similar political platforms, so much rests on the choice of leader. The APC will likely settle on a northerner, in response to a growing feeling that the southern-led government has neglected the needs of the country’s mostly Muslim north.

The selection of a leader from candidates including Mr Abubakar and former military leader Muhammadu Buhari will take place in December, after this magazine goes to press. But the process may be stormy. Analysts argue that in-fighting, politics, and the failure to rally around a single candidate could threaten the party at a time when the PDP has already chosen Mr Jonathan as its presidential candidate. There is still the chance that the coalition could crumble, Ms Tzinieris argued, because the process of deciding jointly on a presidential candidate “will prove particularly contentious”.

The APC’s candidates face the added problem of remodelling their reputations. “Many of the APC’s potential leaders are going to find it hard to escape the image of self-interest, because they have only jumped ship recently,” said Martin Roberts, west Africa analyst with IHS, a risk consultancy. “Atiku has left the PDP twice purely to fulfil the ambition of becoming president.”

These elections will be more closely fought than any since 1999, but in reality, a change of guard is highly unlikely. The PDP will be able to draw on “vast country-wide patronage networks” to maintain power, Maplecroft’s Ms Tzinieris said. Access to oil revenues will also bolster its electoral war chest.

With more at stake than ever, it is widely assumed that the PDP will ensure a victory through whatever means necessary. “This vote will be very well controlled by the PDP,” IHS’s Mr Roberts argued. “Holding on to power is too important to leave to chance. Many senior PDP figures fear that if they did lose power they would spend the rest of their lives fighting off corruption allegations and being pursued in various court cases.”

Vote rigging is likely, he added, but the government has other means at its disposal, including leveraging its control over appointed state police commissioners. The APC also fears that the government will attempt to postpone ballots in the three states under emergency rule in Nigeria’s troubled north-east, where support for the opposition is strong.

Nigeria’s previous presidential vote was among the bloodiest in its history, with over 800 reported dead by Human Rights Watch. With tensions running higher than ever this time around, another outbreak of religious and ethnic unrest is likely. “In the event of a northern APC candidate losing out to Jonathan, there is a real risk that post-election tensions would escalate in northern states as well as the country’s middle belt,” Ms Tzinieris argued.

There may be two parties in the game now, but the birth of a more vibrant democracy poses its own challenges before next year’s vote, scheduled for February 14th. Nigeria faces an unsettling few months ahead.