How to combat graft

Without citizen participation, the fight against corruption is lost

Although African governments have established countless institutions and agencies to fight corruption, graft remains rampant across the continent. Transparency International’s (TI) 2013 Corruption Perceptions Index listed Africa as the second most corrupt region on the globe, with South Asia topping the list. According to the TI report, ten out of the 20 most corrupt countries in the world are found in sub-Saharan Africa.

Governments are easy to blame for graft, but it is citizens who must take action. They can reject corruption in their everyday lives and they can vote corrupt officials out of office, when elections are free and fair.

“Although institutions and laws are important, involvement of [the] public in the fight [against corruption] is fundamental,” said Patrick Lumumba, law lecturer at the University of Nairobi, who served as the director of the Kenya Anti-Corruption Com- mission (KACC) from July 2010 to August 2011, before Kenya’s parliament restructured the commission.

Resources and attention ought to be directed to helping to instil a strong contempt for corrupt practices in Kenya’s citizenry, Mr Lumumba added. “I am extremely dismayed by the public who continue to stand aside as spectators and leave the anti-graft agencies to fight the vice,” he said.

Unfortunately the culture of corruption runs so deep in Kenyan society that it has become an onerous and unavoidable part of everyday life.

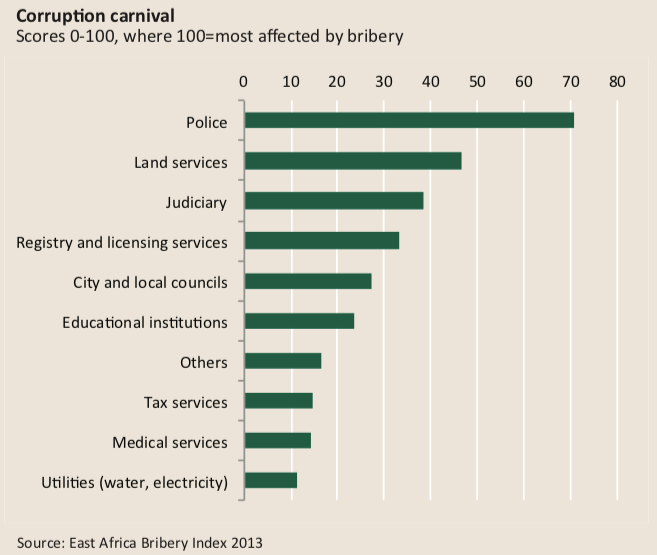

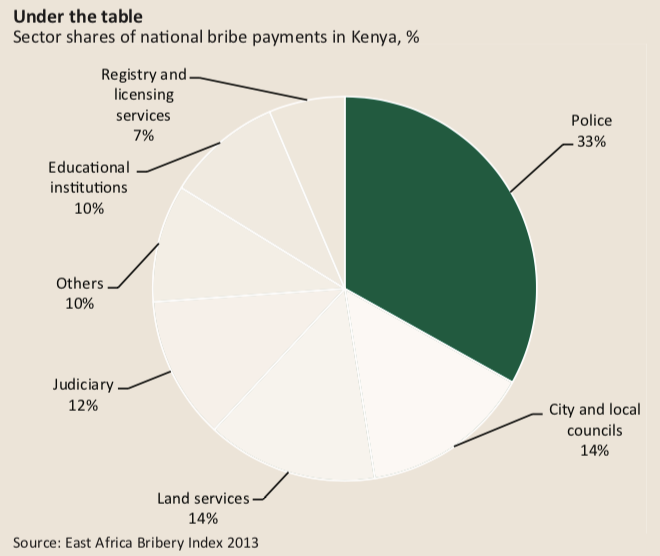

“Corruption is a burden to many of us trying hard to make a living in the trans- port industry,” said Alfred Macharia, a minibus taxi driver in Nairobi. “We have to include it [bribes to police] as part of the operating costs.” Giving bribes every day is the only way to remain in business, he said, adding that he pays $15 a day to different police officers along his route and a $30 monthly fee to other designated cops.

The harmful effects of this graft go even deeper. After a vehicle crashed and killed 13 people on April 5th, Alfred Mutua, the governor of Machakos County in eastern Kenya, blamed traffic police for taking bribes and failing to enforce traffic laws.

Police are mandated to check that all minibus taxis are fitted with speed governors to ensure that they keep to speed limits. If a policeman “shamelessly accepts as little as 50 Kenyan shillings” [less than a dollar] to allow a noncompliant taxi driver to proceed, “does he know the dangers he has exposed the country to?” Mr Mutua asked.

Police heads, including David Kimaiyo, inspector general of Kenya’s police service, live in denial, often saying that only a few officers are engaged in corruption. This defensive mentality hurts efforts to reduce corruption.

The culture of graft is hurting economies and ordinary people across the continent every day. Kenya provides a sobering example of the harmful effects of corruption. In its 2013 index, TI ranked Kenya 136th out of 177 countries. These perceptions put off investors who otherwise might help the country to grow the economy and provide jobs for its people. Although it is difficult to quantify the extent of the loss that results from corruption, the World Bank estimated in 2012 that graft could lead to the loss of about 250,000 jobs annually.

The Kenyan government is again in the spotlight for questionable deals involv- ing tenders for the multibillion-dollar standard gauge railway project, the National Social Security Fund-Tassia housing project, and a school laptop programme. There have been notable concerns that corruption has permeated Kenya’s public procurement and contracting processes, and the country is losing billions through dubious deals in the tendering of public projects.

Kenyan’s loss of faith in public officials and institutions is due partly to government’s failure to charge and convict those accused of corruption, analysts said.

But the problem lies not only with government, according to Duncan Okello, chief of staff in the office of Kenya’s chief justice. If the country “established a strong value system that shuns corruption and makes it expensive, the vice would go away”, he said. “However, Kenyans seem to celebrate corruption and corrupt individuals as they elect and adore leaders who lack integrity.”

Even worse, politicians use the ethnic card to fight corruption allegations, Mr Okello observed. They quickly rally their ethnic communities for support, arguing that it is the community and not the individual that is targeted.

Education could go a long way in helping the public to detect and reject corrup- tion. The Ethics and Anti-Corruption Commission (EACC) is a public body established in 2011 to replace the Kenya Anti-Corruption Commission (KACC). It started a programme in 2012 that runs clinics and events in 15 of Kenya’s 47 counties on how to avoid, report and stop corruption. The project targets workers in government institutions, churches, media and business. In addition to the anonymous reporting on its website, the agency has set up a whistle blowers’ protection programme.

The agency also partners with the Kenya Institute of Education (KIE) to promote the teaching of “values”, particularly integrity, in the school curriculum. This is intended to persuade young people that corruption is unacceptable, said Irene Keino, the EACC’s vice-chairperson.

Already the KIE has started highlighting topics related to integrity in the main- stream school curriculum. “For example, when teaching languages, teachers include passages that touch on values and integrity-related issues,” said Antony Maina, a cur- riculum development specialist at the Kenya Institute of Curriculum Development in Nairobi. “Another way of teaching integrity is to make use of newspaper articles that touch on corruption-related topics.”

Top-down approaches have been tried and failed. If the public is not included in the fight against corruption, there is no chance of rooting it out.

Raphael Obonyo is a public policy analyst. He’s served as a consultant with the UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs (UNDESA). An alumnus of Duke University, he has authored and co-authored numerous books, including Conversations about the Youth in Kenya (2015). He is a TEDx fellow and has won various awards.