The Chinese in Botswana and Zimbabwe

Both countries use Chinese companies to build infrastructure. Guess which one applies strict controls?

by Kevin Bloom

When measured against the performance of President Ian Khama of Botswana, the dismal governance record of Zimbabwe’s President Robert Mugabe should come as no surprise. The big revelation in such a comparison is to be found in just how wide the governance gap between these two state leaders extends—especially when the evaluation concerns large-scale infrastructure projects in their respective countries.

The top-line numbers provide an important backdrop. On a scale of zero to 100, where zero counts as “highly corrupt” and 100 as “very clean”, Transparency International’s 2012 Corruption Perceptions Index gave Botswana a score of 65. The figure placed the country in 30th position out of 176 countries measured, the highest of any African country on the list. Against this, Transparency International gave Zimbabwe a score of 20, which placed it in 163rd place—on a par with Equatorial Guinea, and only slightly above Burundi, Chad, Somalia and Sudan.

The latest index, which takes into account bribery of public officials, kickbacks in public procurement and the enforcement of anti-corruption laws, showed that Zimbabwe had dropped nine places against the 2011 rankings. Botswana, on the other hand, had risen by two places, a jump that served to bolster Mr Khama’s reputation as a champion of African governance.

In August 2013 Mr Khama’s cabinet further cemented this reputation—in the eyes of the West at least—by adopting a stance on the Zimbabwean elections contrary to the official stance of the Southern African Development Community (SADC).

“There is no doubt that what has been revealed so far by our observers cannot be considered as an acceptable standard for free and fair elections in SADC,” said Botswana’s foreign affairs minister, Phandu Skelemani, in a statement on August 5th, five days after Zimbabweans had gone to the polls. “The community, SADC, should never create the undesirable precedent of permitting exceptions to its own rules.”

In any comparison between Botswana and its eastern neighbour, Mr Khama’s lone-star foreign policy must be taken into account. When comparing Chinese-funded infrastructure projects in Botswana and Zimbabwe, it appears that Mr Khama’s outlier status is reflected most prominently in his application of a strict set of governance standards. In Zimbabwe, by contrast, Mr Mugabe’s attitude would appear to be characterised by the absence of such rules.

The situation in the former has been a matter of public record for some time. According to Mmegi(the “Reporter” in Setswana), Botswana’s major news daily, the Sinohydro Corporation has been feeling the sharp end of Mr Khama’s rules for the last 18 months.

As the world’s largest hydropower firm and one-time employer of former Chinese president Hu Jintao, the Sinohydro Corporation was until July 2013 the most visible international contractor in Botswana’s infrastructure space. Its halcyon years were by all accounts 2010 and 2011 when it deployed 600 staff to the country and was active on five major projects, according to a Sinohydro manager, a Mr Xu, who was reluctant to provide a full name.

The corporation’s largest project in Botswana was the Dikgatlhong dam, a few kilometres below the confluence of the Shashe and Tati Rivers in the country’s north-east. Sinohydro’s second in size was the new terminal at the Sir Seretse Khama International Airport in Gaborone, the capital; third was the reboot of the 80km road from Francistown to the Zimbabwean border; fourth, the rehabilitation of the 115km Kang-Hukuntsi road in the country’s west; and last the Lotsane dam in the east.

As of December 31st 2010, according to China Daily newspaper, Sinohydro was working on 261 projects in 55 countries across the globe; in October of that year, China Radio International had pegged the sub-total of African countries in which it was active at 21. In revenue terms, Africa was said to account for over 40% of the $4 billion the corporation had generated off overseas projects in 2010.

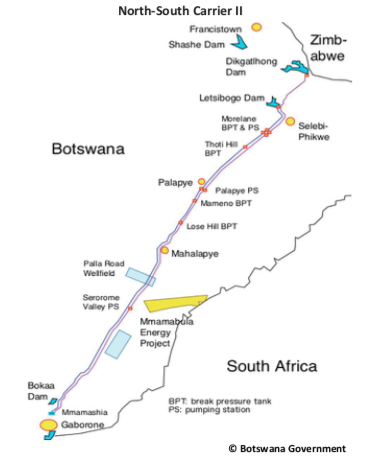

During a four-day research trip in January 2011, I visited Sinohydro’s signature project in Botswana, the Dikgatlhong dam, the largest civil engineering project under construction anywhere in the country. The $153m development was meant to take 47 months to complete, and all was on schedule during the week of my research in month 35. When operational, Dikgatlhong would be Botswana’s primary dam, with a capacity of 400m cubic metres and a 74km pipeline feeding water into Gaborone, part of the north-south carrier scheme. Environmental and archaeological consultants had delivered detailed impact assessments. The Botswana government had paid the villagers of Polometsi and Matopi $96,000 for relocation (the dam had wiped out their villages), plus a further $179,000 for exhumation and reburial of their dead.

The principal engineer on the project was Boikanyo Mpho, a Botswana national employed by the engineering consulting firm Bergstan Africa, based in Gaborone. Dikgatlhong was part of a large-scale initiative by the Botswana government to secure potable water for a country where the resource is scarce, he explained. The “water strategy,” as he termed it, falls within a broader infrastructure and development plan. The green light for Dikgatlhong’s construction was a function of careful demand projection: a calculation that showed the dams in and around Gaborone would require an additional feeder source by the year 2015.

As for the tender process, Mr Mpho was adamant that the strictest evaluation criteria were used to choose Sinohydro. In Botswana, he said, it is customary to re-tender at every stage of an infrastructural development project, a rule that applies as much to Bergstan Africa as to Chinese corporations. In addition, all Dikgatlhong contracts were bound by the terms of the International Federation of Consulting Engineers (FIDIC), a global association that safeguards service quality.

But FIDIC, it appears, failed to ensure an acceptable “quality of service” in Sinohydro’s case, at least

as far as the Botswana government was concerned. The first public sign that the Chinese giant’s working

relationship with the government of Botswana had deteriorated was in March 2012, when Mmegi reported that five unfinished projects, poor performance and a heavy workload had cost Sinohydro the North-South Water Carrier II project (a new pipeline which duplicates an already existing pipeline that runs from the north of the country into Gaborone). The Public Procurement and Asset Disposal Board (PPADB) had awarded the 1.5 billion pula ($175m, as per mid-August 2013 exchange rates) tender to fellow Chinese companies, the Consolidated Companies and Quingian Group.

Sinohydro challenged the PPADB’s decision before the finance ministry’s complaints review committee, according to Mmegi. When they lost this appeal, the company turned to the High Court. In its defence, the PPADB and various government departments compiled a dossier on Sinohydro which argued that all five Sinohydro projects in Botswana were either over schedule or unsatisfactory, and that the award of the North-South Carrier tender “would have been too burdensome on the company”. In other words, Mr Khama’s government felt that Sinohydro’s failure to fulfil its contractual obligations on its previous projects disqualified it from winning the contract on the new project.

Then Mmegi published a story in July 2013 that stated that Sinohydro was moving out of the country. The lead came from an item in the Botswana Advertiser newspaper and website, which indicated that the corporation was selling off its assets, including cranes, scaffolding, construction tools, vehicles and office furniture. The Chinese conglomerate has so far declined to comment, but there is ample evidence to suggest that the intense scrutiny of its processes, as brought about by the court case which Sinohydro itself instituted, has led to an irretrievable breakdown in its partnership with the Botswana government.

Zimbabwe by comparison, has not applied the same level of inspection to its Chinese contractors. The most prominent Chinese contractor in the country is the Anhui Foreign Economic Construction Group, which according to the Zimbabwe Independent, one of Harare’s last remaining non-state newspapers, “is connected to the military- industrial complex in China”.

In February 2011, a week after my research trip to the Dikgatlhong dam in Botswana, I attempted to gain access to what was then Anhui’s largest construction project in Zimbabwe, the National Defence College on Harare’s old Mazowe Road. Access to members of the foreign press, however, was strictly prohibited. Later reports would confirm that while Anhui had been involved in a number of relatively benign projects across Africa—including the construction of army and police barracks in Ghana—its presence in Zimbabwe was stained with controversy. Amongst other reports, an investigation by the Zimbabwe Independent revealed that Anhui is a 50% joint owner in Anjin Investments, the country’s largest diamond mining concern.

At a cost of $98m, the state-of-the-art National Defence College opened for business in September 2012. At its inauguration, Mr Mugabe proclaimed that the military school’s purpose was to serve as a “think tank” on security

matters, a “bulwark against Western countries pursuing a ‘regime change’ agenda”. The college is reserved for Zimbabwean military personnel of the rank of colonel, group captain or higher—and their equivalents in state security, prisons and the police. Over a period of 13 years, according to South Africa’s Mail & Guardian newspaper, the Zimbabwean government will pay back the Chinese loan for the college’s construction, in the form of diamonds mined from the Marange fields in eastern Zimbabwe.

The China Export-Import Bank, a state entity that promotes trade and investment, supplied the loan for the college, the Zimbabwe Independent noted in June 2012. The newspaper quoted from a letter signed by the country’s acting secretary of mines and addressed to Anjin Investments as evidence that this loan is guaranteed by access to the Marange field. But what the Harare-based weekly broadsheet did not mention (perhaps because it assumed its readers were well acquainted with the story) was what The New York Times had written of Marange in December 2011.

The Times piece noted that Global Witness, a London-based campaigning group, had resigned from the Kimberley Process, the coalition set up in 2003 to stem the flow of so-called conflict diamonds onto the world’s markets. “Global Witness had expressed concerns about how the Kimberley Process was operating for some time,” stated the article. “The final straw was the decision last month to allow Zimbabwe to export diamonds from the Marange fields, where there have been reports of widespread human rights abuses by government security forces.”

Equally controversial is the identity of Anhui’s partners in Anjin Investments, a group that appears to consist of these self-same Zimbabwean government security forces, although every effort has been made to conceal the names of the shareholders. The entity is “reported to be Matt Bronze”, wrote Jason Moyo in the Mail & Guardian in July 2012, “a shelf company bought by the military to house its investments. Matt Bronze’s directors have never been named publicly, but Anjin’s Zimbabwean directors are almost entirely from the security forces.”

Where does this leave the Anhui Foreign Economic Construction Group? In a relatively good position, it seems. Aside from the abovementioned articles in the Mail & Guardian and Zimbabwe Independent (newspapers both controlled by Zimbabwean national Trevor Ncube) and an extensive report published by Global Witness in February 2012 (titled “Diamonds: A Good Deal for Zimbabwe?”), the activities of the Chinese conglomerate in Zimbabwe have resulted in very little fallout. Anhui’s $124m renovation of the Akii Bua national stadium in Uganda, as well as its $106m contract to upgrade the Maputo International Airport in Mozambique, have not been affected.

On the contrary, as Bloomberg reported in May 2013, Anhui has recently entered into a joint venture with the government of the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), to mine diamonds in that country’s Eastern Kasai province. With the DRC’s mining ministry projecting an output from the venture of 6m carats a year by 2016, the plan is to take the company public on an “unspecified” stock exchange. “As part of its investment,” noted Bloomberg, “Anhui will construct a 4.6-megawatt hydropower plant near Tshibwe [south-eastern DRC] and a new building for Congo’s diamond regulator at the N’Djili airport in Kinshasa, the national capital.”

In Zimbabwe itself, Anhui is currently completing a hotel and shopping complex, said to be worth $200m, adjacent to the National Sports Stadium in Harare.

Ultimately, however, Anhui’s African presence must be weighed against the accusation of Zimbabwe’s former finance minister (Tendai Biti of the opposition MDC-T) who said in 2012 that while Marange diamond operations were producing an estimated $600m a year in earnings, only $30m had been received in tax contributions.

For Chinese construction conglomerates, the difference between doing business in Botswana and Zimbabwe is clearly vast—and this difference has everything to do with Mr Khama’s governance expectations, on the one hand, and Mr Mugabe’s lack thereof, on the other.