Using smartphones to sell music may curb counterfeiting

by Rose Skelton

For years, pirate distributors at the Alabo international market in Lagos, Nigeria’s commercial capital, dominated the music distribution business. These fraudsters had the means to cheaply reproduce music. More importantly, they controlled the distribution network by providing counterfeit hard copies to on every street corner in this West African nation. Even artists, desperate to get their music to the masses, would sell their master tapes to the pirates.

The Nigerian music piracy system became a highly successful — albeit illegal — model for the distribution of hardcopy music that fed the voracious demand for musical entertainment in Nigeria. About four years ago, the police and the Nigerian Copyright Commission (NCC) began cracking down on illegally copied CDs and movies. Despite this enforcement, in 2011 the NCC seized over six million fake copies of music, books, and software with a street value of $4.6m. The exact cost of piracy — in lost taxes to the government and revenue to artists — is unknown, but given the quantitie undoubtedly vast.

But consumers in Nigeria and the continent have changed their tune and no longer demand music in CD format. Instead, the mobile phone has become one of the primary devices for buying and selling music.

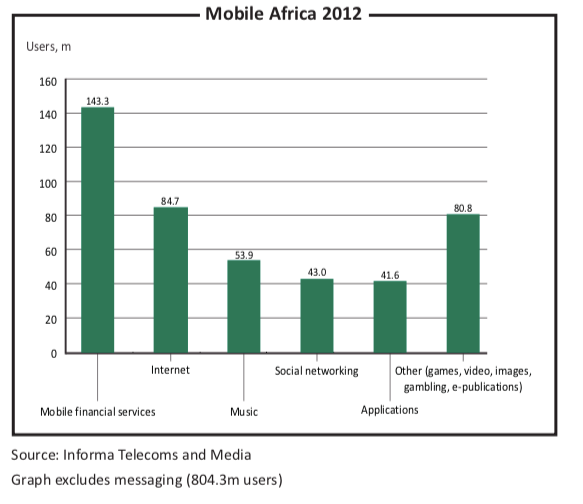

Consumers in Africa use phones not just for talking but also for downloading and listening to music, says Julie Rey, research director of Com World Series, an organiser of digital business events. Consumers also use phones for financial services, social networking and video games. By the end of 2012, Africa had 750 million mobile phone subscribers, and it will have one billion by the end of 2015, according to Informa Telecoms and Media, a United Kingdom-based telecoms and media consultancy.

“Digital music is one of many potential driving forces” of the increase in mobile data plan subscriptions in Africa, says Guillermo Escofet, a senior analyst at Informa. People are willing to pay for a legitimate service, as the growth of pay-for digital music shows.

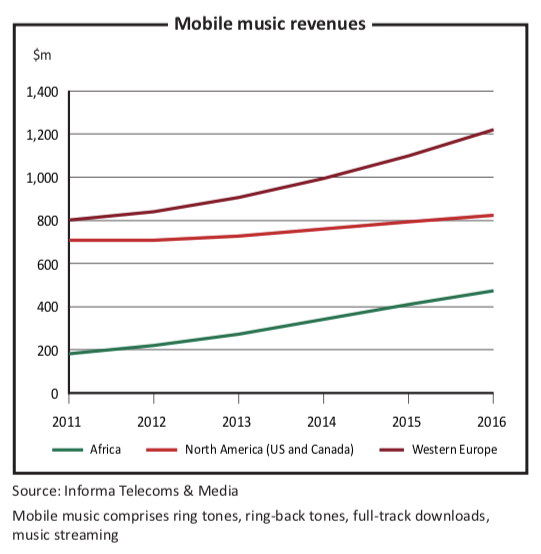

The growth in Africa far outpaces the rest of the world. Informa estimates that mobile music revenue in Africa will be $474m by 2016, more than double the 2012 estimate of $220m. By comparison, North America’s revenue in 2016 will be $824m, up only slightly from $708m in 2012. Mobile phone penetration in Africa exploded in the mid-2000s as pay-as-you-go SIM cards and cheap mobile phones became readily available on the market. There were 54 million new mobile phone subscriptions in West Africa in 2007 alone, according to Informa. The digital music market is set for similar growth across Africa in coming years.

Major record companies like Universal, EMI and Sony, who dominate the music industry outside of Africa, have so far failed to keep up with the demand for music in Africa. They have ignored the African market because they have no knowledge of how to conduct business in it. “The music industry in Africa is completely unstructured and informal,” Escofet says. “If you want to build up a catalogue of music in Nigeria, you have to speak to hundreds of people. In the West, you only have to speak to four labels and you have 90% of the market covered. In Africa, it’s completely fragmented.”

African markets, apart from South Africa’s developed music market, do not have the label tradition, says Karen Liebenberg, general manager at Mondia Media South Africa, a digital entertainment company. Instead, artists sign deals directly with mobile operators. This makes it harder for majors to do business in Africa. “The major labels do not have representatives on the ground,” she says. “This has come with huge problems [in] collecting and distributing rights money.” The technology involved in successful digital distribution is also complicated for a first-time entrant into the digital market. “It’s not that they’re not digitally savvy,” she says, “but they’ve never had to follow those processes. There is a massive gap in understanding the technology.

Infrastructure shortcomings have slowed the launch of digital music platforms to an African audience. “Relying on satellites is costly,” Rey says. But fibre optic development to the continent is making broadband cheaper and more widely available, she adds.

With the rise of smartphones, tablets and faster internet speeds, consumers can increasingly bypass costly broadband packages and download music directly onto their portable devices. Wireless service providers have been quick to catch on to the changing market. “Operators are looking to increase revenues by increasing data downloads,” Rey says. “They are trying to build links with the music business to increase revenue.”

In the meantime, smaller providers have stepped in to fill the void. France Telecom’s Orange launched unlimited music streaming in Côte d’Ivoire and Mauritius earlier this year. “Not only does this incentivise users to buy an operator’s most expensive data plan, but it also supposedly keeps users more loyal,” Escofet says. The French provider is hoping to replicate the success of Spotify, the popular Swedish online music service, which is still unavailable to most of the continent.

Local digital platforms are also racing to fill the market niche created by Spotify’s absence. Spinlet, a Nigerian music download platform, was launched in May 2012 and had 200,000 BlackBerry and Android users just four months later, says Eric Idiahi, the company’s chief executive. “Africa is our market,” he adds, naming South Africa, Nigeria and Kenya as the largest consumers of Spinlet’s product.

“We’re looking at Africa as one of the fastest-growing regions in the world,” says Gerrit Schumann, CEO of German company Simfy, which launched its music streaming service for desktop computers and smartphones in South Africa in August 2012. “We’ve looked at Africa as a fantastic opportunity for growth and South Africa is a natural starting point,” Schumann says. “Our goal is to expand across all of Africa. Potentially in five years time, 30% to 40% of our customer base could be coming from Africa.”

Menyou, a Swedish digital platform, launched its Africa service in early 2012. “Our first music content was African,” says Kisito Diene, Menyou’s Africa manager. “This is the first time a music company is starting from an African point of view and then spreads outwards.”

Menyou’s unique selling point is that anyone can sell music on the digital platform, meaning that artists can upload their own music, share it with fans and make money. This cuts out the record label (Menyou takes 10% of the income, and the artist or aggregator takes the rest), meaning the artist can take a better cut and retains ownership resource provided by Africans living abroad.

“The African diaspora want productions from their own countries but they have to go to Clignancourt [in Paris] or Harlem [in New York] to buy CDs. Now we make it available cheaply on the internet. Most record companies have no knowledge of the African market so they just put a big X on it,” says Diene, a Senegalese who ran some of Dakar’s most successful live clubs before joining Menyou. “African music is not available on the market and we are making that music available.”

As the industry grows, royalty collection societies, songwriters and performers will need to form strong bonds to avoid exploitation by more experienced industry players such as labels, distributors or mobile operators.

Technology such as the ring-back tone, where the owner of the number can set a song for the caller to hear instead of the standard ringing tone, is dominating the digital music market in Africa. The sale of ring-back tones is generating 95% of the digital music revenue in South Africa, with many Indian-owned companies now major players in this market, Mondia’s Liebenberg says. As large corporations, they can afford to offer substantial cash advances to record labels to own digital rights to their catalogues.

They use this ownership as leverage with the mobile operators to work solely with them. The cellular company takes 70% of the profits, leaving 30% for the owner of the music rights, Liebenberg says. The artist, unsurprisingly, is at the very bottom of the revenue chain.

Despite the move from CD to online music buying, piracy continues to be a major problem. Centralised data collection of the African music market does not exist, making it impossible to determine the economic impact of piracy on the continent. But according to Frontier Economics, a UK-based consulting firm, the world value of digitally-pirated music, movies and software may reach $80 billion to $240 billion by 2015, a huge margin because of the nature of this illegal business.

Menyou’s Diene says that new ways of buying music — such as his company’s formula of cutting out the middleman and making digital music cheaper for the consumer and more profitable for the artist — could be a way of countering piracy in Africa. “I am convinced that most people prefer not to buy music because they feel ripped off,” Diene says. “This would change if they saw that the artist is getting a good part of the money.”

The digital music market will echo the fast rise in cheaper smartphones and technology, such as the inexpensive ring-back tones popular with the working classes. “There is no question that the mobile phone is the way they [Africans] want to get their music,” Liebenberg says. “Online [music distribution] will be very slow to roll out because of internet penetration but in terms of mobile, without question, things will change very quickly.”