Foreign ownership of African land: beneficial or exploitative?

by Simon Allison

Some call it neo-colonialism. Others say it is Africa’s hidden revolution. Still others term it a disaster waiting to happen. Whatever the phrasing, the headlines and reports are uniformly grim when it comes to land grabbing in Africa, an issue which has dominated coverage of African agriculture over the last few years. Shady sovereign wealth funds or western investors with less than honourable intentions are buying the continent’s land at knock-down prices, claim concerned non-governmental organisations (NGOs).

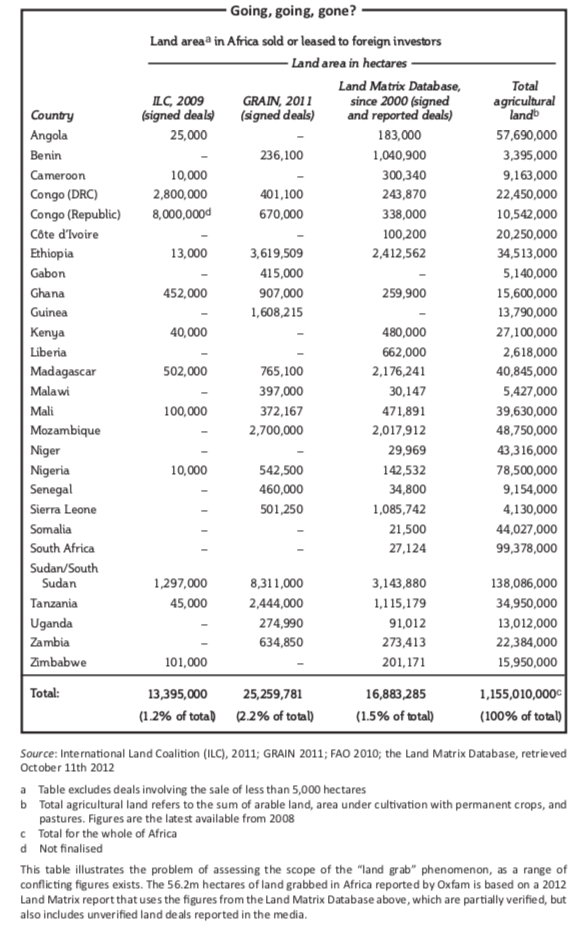

Africa has become the destination of choice for investors looking for cheap, fertile land. According to an October report by Oxfam, an international charity, “62% of reported large-scale land deals for agriculture involving foreign investors in developing countries in the last ten years were in Africa, covering 56.2m hectares, an area equivalent to 4.8% of Africa’s total agricultural area, or the territory of Kenya.”

This report also defined “land grab” as any large acquisition of land in a developing country by a foreign investor (large being more than 200 hectares—ten times the size of a typical small farm) that flouts human rights, fails to conduct social and environmental impact assessments and/or avoids transparent contracts.

In isolation, each of these deals is troubling, claim critics of the land grab phenomenon; taken together, they represent an existential threat to Africa’s population. This criticism has three main strands. The first centres on the people who use the land and have for generations—even though they do not own it in a conventional, legal sense. Usually the land is government-owned. When the government sells it off, the people are forced off, often without compensation and with just a few weeks’ notice. “All the arable land is being given away without consideration of the rights of people who live on the land,” said Emeka Akaezuwa of the United States (US)-based

Stop Africa Land Grab movement in an interview with Good Governance Africa.

The second is that foreigners are buying Africa’s fertile land, planting and then exporting crops when Africa has plenty of hungry mouths to feed itself. The suspicion here is that African governments are making a quick buck and investor countries are purchasing food security for themselves. Africans—32% of whom are undernourished, according to The Hunger Project, a US-based NGO—are being left out. “There is no thought about feeding the people,” Mr Akaezuwa said. Even worse, many of the reported land grab deals involve lengthy contracts, meaning that even when governments do wake up to the need to feed their people, much of the available land will be inaccessible—and feeding citizens of other countries.

The third concern is even more pressing: water. In June, GRAIN, an advocacy group based in Spain, published an alarming report entitled “Squeezing Africa dry: behind every land grab is a water grab”. The report alleges that every large-scale land deal is located on, or near, an important water source, with potentially devastating impact. “If there is anything to be learnt from the past, it is that such mega-irrigation schemes can not only put the livelihoods of millions of rural communities at risk, they can [also] threaten the freshwater sources of entire regions.” GRAIN’s coordinator, Henk Hobbelink, was even blunter: “If these land grabs are allowed to continue, Africa is heading for a hydrological suicide.”

Taking all this at face value, it is clear that land grabs pose a serious threat to the three most basic needs of people in Africa: access to land, food and water. So, maybe those grim headlines are appropriate, after all.

Or maybe not. Another school of thought suggests that the issue has been blown out of proportion, and that the all-or-nothing demands of NGOs will do more harm than good. Firmly in this camp is the World Bank, which came in for plenty of criticism in Oxfam’s report as one of the world’s largest funders of agricultural projects, to the tune of $5 billion per year. Oxfam suggested that the World Bank could go a long way toward solving the problem by issuing a moratorium on large- scale land deals.

The World Bank, naturally, disagrees. “Taking such a step would do nothing to help reduce the instances of abusive practices and would likely deter responsible investors willing to apply our high standards. Now, more than ever, the world needs to increase investment in agriculture, which is two to four times more effective in raising incomes among the very poor than growth in other sectors,” the Bank said in a press release.

Harry Verhoeven, a researcher at Oxford University, and Princeton fellow Eckart Woertz, support this sentiment. The two wrote the only article in the mainstream media critical of the prevailing land grab narrative. “There is a striking gap between the spectacular headline announcements and the reality that little actual investment seems to have transpired,” the pair wrote for CNN. Their article detailed a number of reported deals that never actually happened and questioned the nature of those that have.

In an interview with Good Governance Africa, Mr Verhoeven explained why the actual figures might not match the hype: “It’s clear that a number of NGOs in their desire to highlight some very important issues and concerns have been exaggerating and overstating a lot of their claims, which partly of course speaks to their need to attract funding. We think it’s unscientific and unsubstantiated by facts.”

The central problem with African agriculture is productivity, Mr Verhoeven said. The way the land is farmed means that it does not produce enough to feed everyone.

Africa’s agricultural revolution requires a substantial increase in productivity, something that is just not possible without creating large commercial farms and investing even larger sums. “The money will have to come from somewhere,” he said. “Some states have cash to go round and a willingness to spend it. How can we make this work for Africa? That’s where the debate should really focus.”

Investment is vital even if some people get hurt along the way. “The NGO idea is that if an investment does any harm at all it shouldn’t be allowed. But all investments harm someone,” Mr Verhoeven said. “We do believe that outside investment, whether private or state or partial, can ultimately be beneficial if the right measures are put in place.

Oddly enough, this is exactly the same solution proposed by Mr Akaezuwa, one of the most vocal critics of land grabbing in Africa. “There should be a strategic approach,” Mr Akaezuwa said. “There should be provision made for the community. There should be environmental protection regulations, and there should be provision made for some percentage of the food to be made available to the community.

The idea is to have investment that is a win-win situation, where the company makes money, which is the point of investing, and the people benefit, too.” Of course, while all parties can agree that investments need to be more accountable and equitable, this still leaves considerable room for disagreement. Is it fair to force local communities to move if it increases productivity? Can the benefits of jobs created in new farms outweigh the loss to the state of arable land? And who has the final say—foreign investors with the money, governments who own the land, or the people whose futures are at stake?

Clearly, land grabbing is a complex issue. NGOs such as Oxfam, GRAIN and Stop Africa Land Grab should be lauded for raising it. Greater scrutiny of what investments are taking place and their impact is vital to ensure that the development of Africa’s land is in the interests of Africa’s people. However, by exaggerating the threat posed by land grabbing and failing to differentiate between necessary, beneficial investment and exploitative investment, advocacy groups risk derailing both—at a huge cost to Africa’s agricultural productivity, which needs large cash injections from somewhere. Ironically, advocacy groups—if they are not careful—risk entrenching African hunger through their attempts to protect the continent’s land.