Members of the Forum of Friends of the Sahel (FFS), a shadowy anti-West and pro-Sahel group operating in Cotonou, Benin’s economic capital, begin their daily “meeting” by discussing a video purporting to show a secret French military base in Kandi, northern Benin, located about two hours from the Niger border.

The fake video, which went viral, is one of the numerous products of artificial intelligence (AI)-generated deepfakes currently wreaking havoc in West Africa. Relations between the two countries have deteriorated since the 2023 military coup that toppled Niger’s democratically elected president, Mohamed Bazoum.

“This is the site where France stores all the weapons it supplies to terrorists who kill our people and soldiers, and this is where French and Beninese soldiers are planning an attack on Niger to reinstate Bazoum,” one member told Africa in Fact in broken French, which seemingly demonstrated his precarious level of education.

Pro-Russia and China, the FFS is a cohort of migrant workers from Mali, Burkina Faso, Niger, and Guinea who specialise in collecting AI-generated fake videos, which it anonymously distributes to its network of followers across the region.

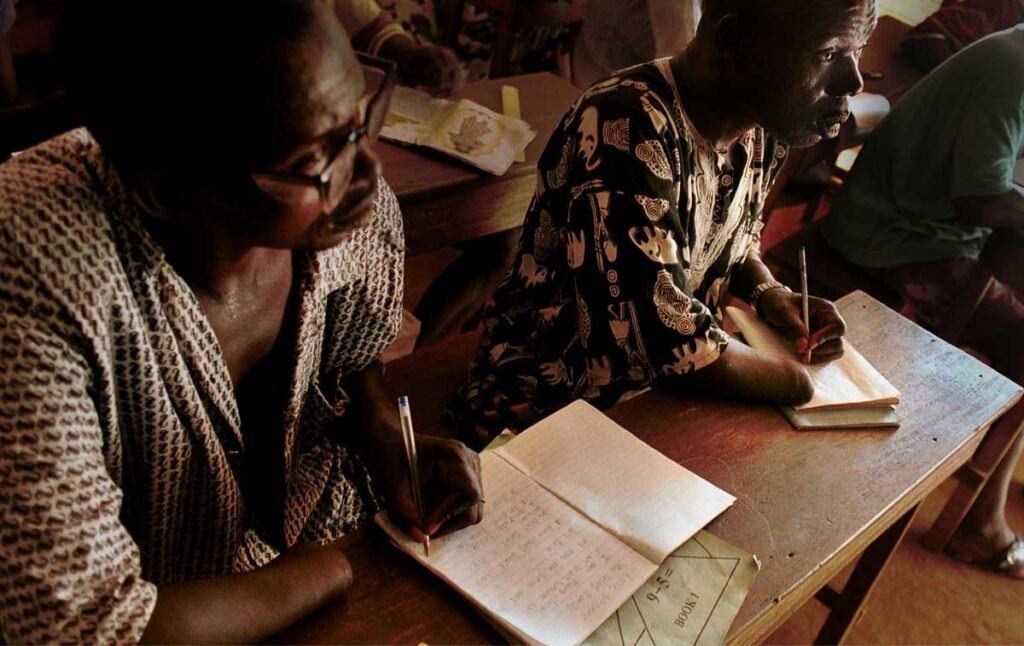

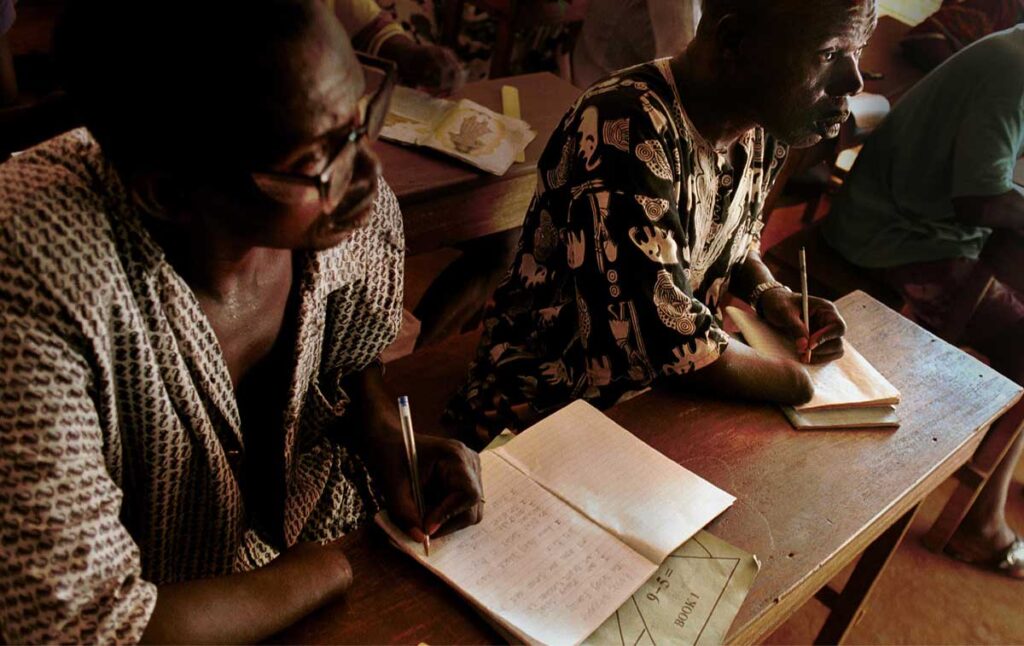

The FFS claimed to have “hard evidence” pointing to the complicity of the European Union to destabilise West Africa, However, a Sahelian activist and former schoolteacher, who fled to Benin in the aftermath of a military coup in his country, said FFS members could not be trusted because they were a bunch of illiterate folks who could not even write their own names.

“Most of them are a disaster, and easy targets to manipulate by those who supply them with deepfakes because they are illiterate. None of them has even a little understanding of geopolitics, international diplomacy, economics, regional integration and humanitarian law, let alone artificial intelligence,” the man named here as Amadou said.

He described the discussion he had with group members as hollow and totally unintelligent. “I was quickly branded a traitor and a pro-France supporter when I tried to make them understand that most of what they described as hard evidence of the West’s funding terrorism was baseless, untrue and cooked up by Russia-allied groups from artificial intelligence.”

Amadou said Russia’s AI-generated disinformation campaign, some of which is produced by groups such as Copycop, seemed to be bearing fruit across the world.

According to the Africa Center for Strategic Studies, disinformation campaigns seeking to manipulate African information systems have surged nearly fourfold since 2022, triggering destabilising and anti-democratic consequences and targeting at least 39 African countries.

Nearly 60% of disinformation campaigns on the continent are foreign state-sponsored – with Russia, China, the United Arab Emirates (UAE), Saudi Arabia, and Qatar as the primary sponsors, the Africa Center for Strategic Studies found.

Dr Mark Duerksen, Strategic Communications Manager and Research Associate at the Africa Center for Strategic Studies, told Africa In Fact that Russia, targeting Mali, Burkina Faso and Niger, was sponsoring a number (18) of sophisticated campaigns that were using synchronised fake, hired, and bot accounts (coordinated inauthentic behaviour).

“The campaigns seem to be operated by real people either in the region or abroad. Elsewhere, Russia is starting to use AI to generate content that these accounts post and is giving it specific instructions to create content that drives cynicism and anger, so it is possible that the Russia-linked Sahel networks are doing something similar,” Duerksen said.

False and misleading information, supercharged with cutting-edge artificial intelligence that threatens to erode democracy and polarise society, is the greatest immediate risk to the global economy, the World Economic Forum (WEF) said in its Global Risks Report 2024, published in January.

The authors worry that the boom in generative AI chatbots like ChatGPT means that creating sophisticated synthetic content that can be used to manipulate groups of people will no longer be limited to those with specialised skills.

Amadou said it was obvious that disinformation and fake news fed on illiteracy. “The more people are illiterate, the more they will accept fake news and believe in everything they see on social media,” he said. “West Africa is swimming in a sea of AI-generated disinformation, leading to worrying levels of anti-West sentiment.”

Photo: Chris Hondros/Getty Images

The region’s literacy rate, which stands at 54.1%, is the continent’s lowest and lags far behind southern Africa’s 80.3%, Africa’s highest. Niger, Mali, Burkina Faso, Benin, South Sudan and Central African Republic have the lowest literacy rates in Africa and are ranked among the world’s “illiterate” nations located on an “illiterate” continent.

Prof Tawana Kupe, independent media academic and former vice-chancellor and principal at the University of Pretoria, seemed to agree, telling Africa in Fact that there was a correlation between illiteracy and levels of belief in sources of information, legitimate or illegitimate.

“An illiterate person cannot question information they receive because they are not in the habit of consuming and cross-checking information they receive,” he said. “They also do not have the context gained from multiple sources [to assess] the information they receive. So, there is a strong tendency to believe the information received, especially if it resonates with myths, general beliefs, and talk circulating in their circles.

“They also do not have the means to check and double check information. Finally, lack of indication predisposes them to believe what comes from media platforms.”

Melody Musoni, policy officer at the European Centre for Development Policy Management’s (ECDPM) digital economy and governance team, said not everyone was aware of the fact-checking tools available, which led them to accept fake news at face value. “Also, the more trending a fake social media posting is, the more people are likely to believe it to be true.”

She also noted that people also believed fake news because social media and digital platforms were not doing enough to take down this material. “These companies need to do better.”

Though Musoni agreed that illiteracy played a role in the spread of disinformation to some extent, she said it was not about lack of intelligence or education but rather about generational habits. “Those who have always read print media (usually the older generation) still rely on the electronic versions of their news platforms.

She also pointed to the younger generation’s aversion to following the news and reading newspapers. “We need to ask ourselves why,” she told Africa in Fact. “One thing that jumps out for me is that traditional forms of media [in Africa] are still state-owned. There is very little diversity in terms of what is offered.

“There is a lot of state propaganda (Zimbabwe, where state broadcasters have been criticised for lacking the diversity of offerings to attract a younger viewership, is a good example). This makes it boring for young people to keep up. I also think that ‘trustworthy news’ from traditional sources is now subjective. Personally, I don’t believe everything I read from state-owned media either. There is also misinformation depending on the narrative they want the masses to believe.”

On 10 May this year, Niger’s state-owned Tele-Sahel (ORTN) broadcast fake images of the Benin-based French military base mentioned above. The fake video was also broadcast on the YouTube channel of Russia-funded mouthpiece Afrique Media, where it was viewed, liked and commented on thousands of times.

“It is not only Russia, China and Gulf countries that are bombarding Africa with fake news; governments, armed groups, the corporate sector and ordinary citizens have also taken advantage of AI to manufacture their own deepfakes to promote their respective agendas,” Amadou said.

The Center for International Governance Innovation said it all in a 2022 report that noted that fake news came from numerous sources. “In West Africa, several online and offline actors typically create and disseminate fake news,” the report said.

“These can include individuals, the state, foreign actors, diaspora communities, the media, specialist consultancy firms, online influencers and automated bot networks. Some do it for financial gain; some, for political influence; still others are part of wider efforts to maintain authoritarian systems.”

Kinshasa-born Issa Sikiti da Silva is an award-winning freelance journalist. Winner of the SADC Media 2010 Awards in the print category, he has travelled extensively across the African continent. He lived in South Africa for 18 years, where he worked for 10 years as a journalist before leaving for West Africa, and later to East Africa, to work as a foreign correspondent. He is currently based in Dakar, Senegal.