East Africa: non-tariff barriers

Non-cooperation and governmental indifference are blocking the region’s commerce

Trade barriers that restrict imports and a lack of political will to remove them impede commerce in east Africa.

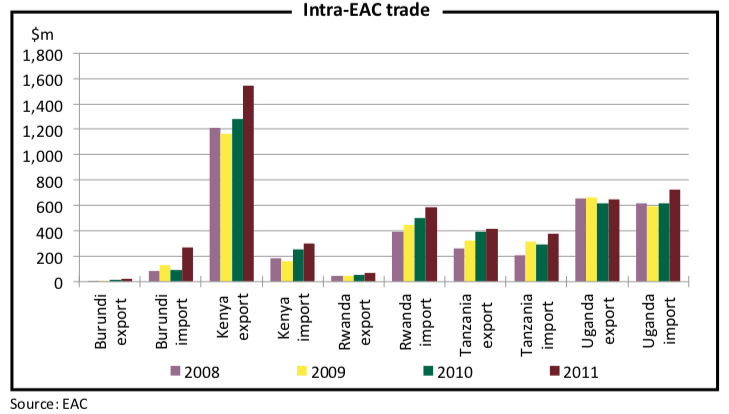

This is an old problem that Burundi, Kenya, Rwanda, Tanzania and Uganda have been trying to fix since they joined forces in 2000 to form the new East African Community (EAC). In 2010 these five countries adopted a common market protocol calling for the “maximum” removal of non-tariff barriers (NTBs) such as onerous documentation, slow border posts and import quotas. This move yielded almost immediate results: intra-EAC trade volumes expanded 22% from $4.5 billion in 2011 to $5.5 billion in 2012, according to a 2012 EAC report.

However a long journey remains. “NTBs continue to inhibit the free movement of goods and services,” said Richard Sezibera, the EAC’s secretary-general, at an EAC summit held last November in Kampala, Uganda.

NTBs come in many forms. These include product quotas, which are used to protect a domestically produced commodity from competitive imports, and onerous employment regulations that require citizens from other EAC countries to pay expen- sive work permit fees. Police corruption, lengthy customs procedures and inadequate transportation infrastructure are other trade barriers.

These hurt industry throughout the region, says Betty Maina, CEO of the Kenya Association of Manufacturers. For instance, it takes a truck 52 days to move goods from Mombasa port to Uganda’s capital, Kampala, a distance of 1,175km, Ms Maina observes, instead of the 11 days recommended by the common market protocol. She blames this sluggishness on corrupt police officers who erect illegal roadblocks.

Progress on the elimination of trade restrictions has been slack mostly because EAC countries lack political will and rivalries still divide them, according to a joint 2014 World Bank and EAC report. Tanzania’s port at Dar es Salaam, its capital on the Indian Ocean, fears competition from Kenya’s Mombasa harbour. Both countries are competing to service landlocked Burundi, Democratic Republic of Congo, Ethiopia, Rwanda and South Sudan. Tanzania and Kenya are also vying to control the transport arteries used to move goods between the interior and the coast.

Tanzania’s apparent unwillingness to participate in joint EAC measures that would accelerate greater collaboration prompted leaders of Kenya, Rwanda and Uganda to create what they called the “coalition of the willing”, isolating Burundi and Tanzania. Kenya has been pushing for South Sudan, which would likely be a part of this coalition, to join the EAC. However, South Sudan’s ongoing civil conflict and lack of functioning institutions have dented its membership prospects.

The disagreement has revived memories of 1977, when the original three- member East African Community of Kenya, Tanzania and Uganda collapsed after ten years of existence. Political differences, especially between Tanzania and Uganda, and the disparate economic systems of socialism in Tanzania and capitalism in Kenya, among other reasons, are blamed for the breakdown.

Since the launch of the 2010 common protocol, Rwanda, Tanzania and Uganda have introduced more trade barriers: at least ten new restrictions on the movement of capital. Capital controls—such as transaction taxes or exchange controls—were the most severe investment-curbing restrictions, according to the World Bank/EAC report. For example, Burundians and Tanzanians were locked out of the January 2014 sale of shares in Bralirwa, Rwanda’s largest beer brewery.

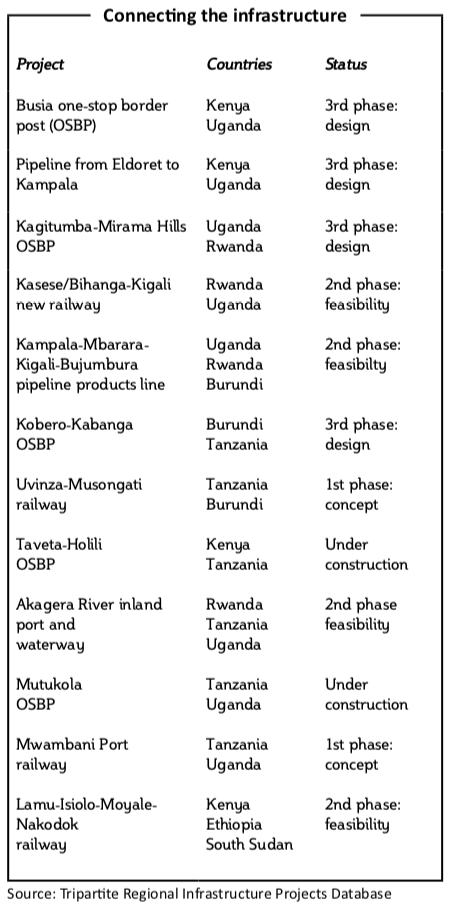

Despite these constraints, the EAC’s five countries are collaborating on several major infrastructure projects, including the $1.4 billion rehabilitation of the Dar es Salaam-Mwanza railway line, expected to link Dar es Salaam Port with landlocked Rwanda, Burundi and Uganda, Mr Sezibera says. The EAC is also working on five road corridors, covering a total of 12,000km. Additionally, the bloc has identified strategic energy projects that would ease the burden of power costs to investors, said Shem Bagaine, Uganda’s acting minister of East African Affairs last November.

The Nairobi-Addis Ababa standard gauge railway line will open the EAC to trade and investments with Ethiopia and South Sudan. The timeline of these projects remains unclear.

The EAC aims to launch a single currency within the East African Monetary Union (EAMU) by 2023. Legal foundations and an East African Central Bank need to be established first.

“The proposed monetary union will require a regional institution responsible for the single monetary and exchange rate policy,” said XN Iraki, senior lecturer at the University of Nairobi Business School. “This may take the form of a central bank, tasked with providing centralised decision-making on monetary and exchange rate policies.”

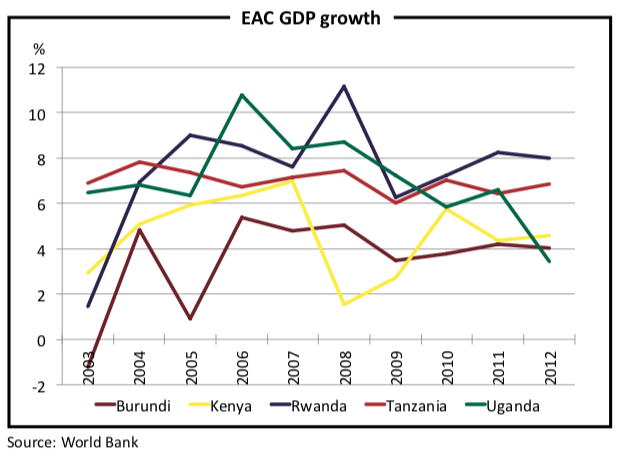

The five EAC countries have different economic cycles, a problem that may delay the creation of the monetary union. Tanzania is the only country that recorded stable growth between 2003 and 2012, according to the World Bank. In the same period, Burundi’s ranged between -1.2% and 4%. Similar disparities have brought chronic instability to the euro zone.

The launch of a single currency in East Africa could promote intra-EAC trade and investment, improve price comparisons, increase competition and reduce onerous foreign exchange transactions. However, this will not be possible unless the leaders of the EAC member states reduce the barriers and boost intra-regional trade. As Mr Iraki explains: “There can be no EAC currency if there is no EAC trade.”