Zambia: renewed calls for Barotseland to secede

President Sata broke his 2011 campaign promise to restore the kingdom’s autonomy

By Victoria Kelly

In August, in a small, badly-lit room in a house in Mongu, the impoverished capital of Zambia’s Western Province, a late middle-aged man with a receding hairline called Afumba Mombotwa was filmed taking oath as administrator general of a “new state”, Barotseland.

Wearing a dark suit and tie, and standing erect in front of a grey curtain, his right hand raised in the air, Mr Mombotwa, 58, swore to protect, defend and uphold the constitution of Barotseland, which he said had been a “stateless nation” under Zambia’s control for the past 50 years. In the background, birds and farm animals and the occasional sound of a car could be heard.

The public declaration of independence was the latest in a series of increasingly bold moves by a group called Linyungandambo, which has been in the public eye in Zambia since the run-up to the Mongu riots of January 2011. The group was a key instigator in the unrest that led to those demonstrations three years ago, when protestors calling for secession from Zambia clashed violently with police. Two people were reported to have died during the riots and over 100 were arrested.

Mr Mombotwa’s August declaration, which was uploaded to YouTube and the group’s other main web outlets including the barotsepost.com and a Facebook page of that name, prompted a wave of arrests on treason charges. These arrests have heightened tension in a region that has been beset by political unrest and calls for secession since shortly after Zambia’s independence in 1964.

Western Province, the south-western portion of Zambia that borders Angola and Namibia’s Caprivi Strip, was created in 1969, five years after Zambia’s independence. Until then, the region was known as the Kingdom of Barotseland, an area that stretched far beyond the modern province’s borders. It was inhabited by the Lozis, a complex language group made up of over 20 different tribes. Today’s Western Province covers an area of 126,386 square kilometres, but Barotseland is estimated to have been twice as large at certain points in its history. Some claim the kingdom stretched into Namibia and Angola and included other parts of Zambia, including its central Copperbelt province, south-west of the Democratic Republic of Congo’s Katanga province. These historical borders were never fixed, however, and are difficult to confirm.

Under British colonial administration, Barotseland had enjoyed relative autonomy since the late 1800s. The Litunga, the Lozi word for the king of Barotseland, had negotiated agreements first with the British South African Company (BSAC) and then with the British government that ensured the kingdom maintained much of its traditional authority. Barotseland was essentially a nation-state, a protectorate within the larger protectorate of Northern Rhodesia. In return for this protectorate status, the Litunga gave the BSAC mineral exploration rights over Barotseland.

In the early 1960s, rather than seek independence from Northern Rhodesia in its own right, Barotseland chose to be part of an independent Zambia, as long as the Litunga and the Barotse National Council (BNC), the highest decision and policy-making body in the Barotse governance system, retained some authority. This included power over some of the region’s potentially lucrative natural resources, such as land, its forests and fishing, and over customary laws and practice.

The Barotseland Agreement of 1964 enshrined these rights, although there is no mention in the agreement that this power extended to minerals.

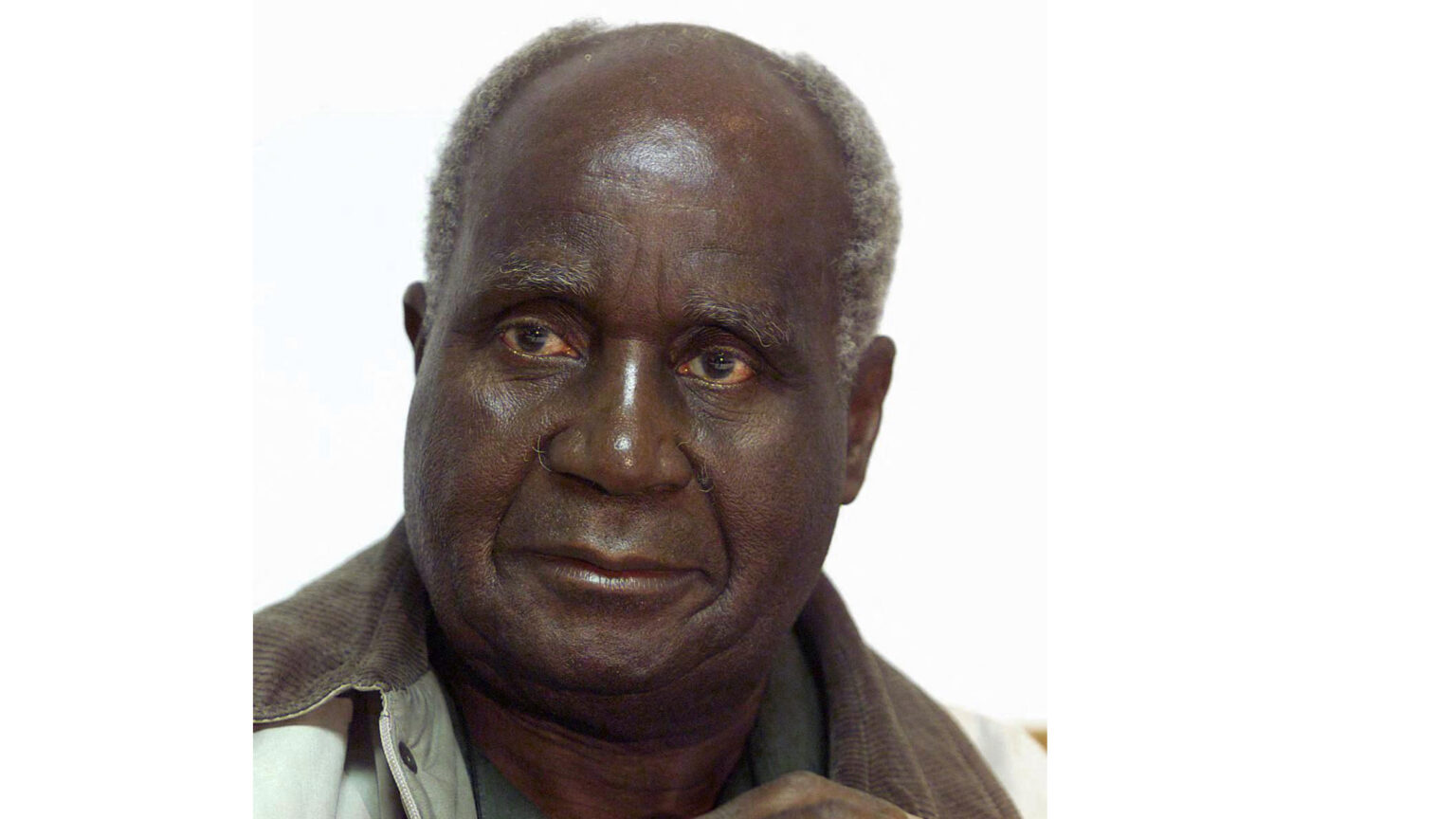

It is this document – or rather its subsequent annulment – which has caused unrest to rumble on in the region for nearly half a century. Within a year of taking office as president of the newly-independent Zambia on October 24th 1964, President Kaunda began to introduce various acts that abrogated most of the powers allotted to Barotseland under the agreement. Most notably, the Local Government Act of 1965 abolished the traditional institutions that had governed Barotseland and brought the kingdom under the administration of a uniform local government system. Then in 1969 Parliament passed the Constitutional Amendment Act,annulling the Barotseland Agreement of 1964. Later that year the government changed Barotseland’s name to Western Province and announced that all provinces would be treated equally.

The agreement’s dissolution and the stubbornness of successive governments in ignoring repeated calls to restore the agreement have fuelled the region’s ongoing tension. This has become a particularly sensitive issue for the current Patriotic Front government led by President Michael Sata. It came to power in the September 2011 elections, winning the Western Province vote largely on the party’s promise to restore the agreement within 90 days, if victorious. Initially, all looked positive for those hoping for its restitution: Mr Sata pardoned the people arrested by the previous government in the aftermath of the Mongu riots and launched a commission of inquiry into those events.

Since then, however, the government’s enthusiasm appears to have waned. The Postnewspaper in March 2012 reported that it had obtained a copy of the enquiry’s findings that recommended reinstatement of the agreement. However, the commission’s report has not officially been made public.President Sata has seemed unwilling to acquiesce, arguing that its restoration would open up a “Pandora’s box” because other chiefdoms would also demand autonomy.

It is perhaps the reluctance of the current government to restore Barotseland’s semi-autonomy that has prompted recent calls for secession from groups like Linyungandambo to grow louder. Mr Mombotwa, a former civil servant who spent two years working in the agriculture ministry followed by 16 years in the foreign affairs ministry, established the group 2010. Linyungandambo means “shake your neighbour” in Lozi.

The group’s emergence has heralded a more militant and uncompromising approach to the Barotse question not seen since the late 1990s when the former president, the late Frederick Chiluba, banned the Barotse Patriotic Front (BPF) for allegedly working with secessionists in Namibia’s Caprivi strip. It was feared that after helping the Namibian secessionists, the two would collaborate to liberate Barotseland and join the two regions into one country. Interestingly, Mr Mombotwa joined the BPF after leaving government in 1999 and remained a member until 2002, although it is not known why he left the group.

Linyungandambo, like other Barotse activist groups, has played on Western Province’s alleged economic marginalisation to gather support. Characterised by its sandy, hostile terrain, the province has few roads, schools or hospitals, and some 80% of its 880,000 population live in poverty, according to Zambia’s central statistical office. Government argues that this is changing. Emmanuel Mwamba, who until recently was permanent secretary of Western Province, says some $1 billion is being channelled into the province to build new roads, a university and a football stadium. But it may be too little, too late.

Linyungandambo’s grassroots approach appears to have struck a chord with the province’s youth, who, frustrated by the province’s lack of opportunity, are hungry for change. However, it is difficult to determine exactly how much support the group has or where that support comes from because no official membership figures exist. Estimates range from around 120 – according to Mr Mwamba – to the somewhat optimistic 1.5m, claimed by Linyungandambo sympathisers who explain that these figures are higher than Western Province’s population because the kingdom comprises a much larger area.

In light of the government’s reluctance to restore the agreement, Linyungandambo is pushing for Barotseland to become a fully independent nation. Neo Simutanyi, executive director for the Centre for Policy Dialogue, says this increased focus on secession has altered recent politics in Western Province. “Linyungandambo has been instrumental in influencing other activist organisations in changing their demands from that of the restoration of the Barotseland Agreement to that of secession,” he says.

Indeed, since its birth three years ago, Linyungandambo has followed an increasingly radical trajectory. In September 2011, shortly before the general election, Mr Mombotwa made a unilateral declaration of independence, announcing himself as administrator general of the “new” Royal Barotseland Kingdom, although there is no legal basis to his claim under Zambian law. The move was announced via the website barotsepost.com, one of the main mouthpieces for Linyungandambo, although it did not receive national coverage. There also appeared to be no public response to the action by either the Litunga or the national council.

Then, in March 2012, representatives from Linyungandambo and other Barotse activist groups, including the Barotse Freedom Movement (BFM) and the Movement for the Restoration of Barotseland, met with the BNC and resolved to nullify the 1964 agreement to enable Bartoseland to revert to its pre-independence status. Mr Mombotwa sat on the BNC committee as Linyungandambo’s representative. The home affairs minister, Kennedy Sakeni, condemned the resolution to break away from Zambia as bordering on treason. “It is illegal to call for secession. We cannot have a state within a state. The people of Zambia gave us a mandate to govern Zambia as a unitary state and it will remain so,” he was reported as saying in an interview in the Times of Zambiaon March 29th.

The video depicting Mr Mombotwa taking his oath as leader of Barotseland’s government-in-waiting in August is the latest public act of dissent. Figures vary, but up to 84 individuals are reported to have been arrested on charges of treason as a result of this and the other secessionist acts. Mr Mombotwa himself has so far evaded capture and is believed to be in hiding in Western Province. At the time of going to press, the detainees were still awaiting trial. The Litunga has not voiced his position on either the BNC’s vote last March or Linyungandambo’s recent declaration of independence, but it understood that he is in favour of restoring the agreement rather than secession, according to Mr Mwamba.

The swearing-in ceremony was a step too far for the other activist groups. The newly-formed Barotse National Freedom Alliance (BNFA), an umbrella organisation that co-ordinates the various Barotse activist groups, publicly dissociated itself from Mr Mombotwa and Linyungandambo. Its chairman, Clement Wainyae Sinyinda, was arrested in September on treason charges for his role in last March’s secession vote by the BNC. He issued a statement on August 22nd denouncing Mr Mombotwa for going against the BNC’s resolution to revert Barotseland to pre-independence status through “a people-driven legal and political process that is anchored in Barotseland’s inalienable rights to statehood”.

The number of recent arrests for treason in relation to secession calls, not just from Linyungandambo but also other groups like the BFM (although it is sometimes difficult to determine to which groups those arrested belong), has led critics to condemn the police and government’s heavy handling of the separatist groups. In February this year, a group of the country’s most powerful Catholic bishops wrote a letter to Mr Sata raising concerns about various human rights issues in Western Province.

In the letter, the bishops observed there was“a climate of intimidation and serious human rights violations currently prevailing in the Western Province: abductions of citizens; arbitrary arrests and individuals being subjected to long periods of interrogations, even torture”.The bishops said that these acts were “totally unacceptable” and implied that the province was in a “de facto state of emergency” – criticisms that are unlikely to have been taken lightly given Mr Sata’s strong Catholic faith. There has also been a government clampdown on online outlets that have given voice to the Barotse issue, with those websites linked to Linyungandambo now blocked to the public in Zambia.

Government admits the police have in some instances been over-zealous in arresting Barotse activists. The information ministry’s Mr Mwamba believes the large number of arrests have wrongly given the impression that the secessionist movement is much larger than it is. Instead, he downplays it as “a storm in a teacup”.

Referring to the most recent round of arrests, Mr Mwamba says: “I was there personally and if the police had acted with a lot of discretion they would not have arrested more than five people. You can’t round up everyone who received a pamphlet in the manner they are doing.”

Nevertheless he admits the group is alarming. “The trouble with Linyungandambo is in their literature they are threatening, which is maybe why the police have taken them seriously. They are collecting materials to form military groups…so that is dangerous in itself.”

Observers argue that groups like Linyungandambo should be given recognition and political space to air their views rather than suppressed through state force. “My fear is that the restriction in the freedoms of the people to express themselves over the Barotseland issue and arrests of its leaders and supporters will not only drive them underground but will lead to a full-blown military insurrection,” warns Mr Simutanyi from the Centre for Policy Dialogue.

The government believes its new decentralisation policy, which cabinet approved in February 2013, will provide a viable substitute for the agreement’s restoration because it will give each of Zambia’s 10 provinces more control over its resources.

However, this is unlikely to solve the problem, says Mbinji Mufalo, a governance and human rights consultant. “There is no devolution of political power in the current decentralisation policy,” he says. “It is simply decongestion of government/public services. Devolution of power is attempted in the [Zambian] constitution draft, but again it falls short of providing the provinces greater self-rule.” Zambia is currently working on a new constitution. A final draft is due to be submitted to the president soon.

For now government and those calling for independence in Western Province have reached an impasse. If the Barotse situation is to be contained, the government will need to manage it gently, something Mr Mwamba recognises. As he explains: “We have to handle the politics well otherwise we can grow a monster out of nothing.”