South Africa’s newspaper wars

by RW Johnson

In the past few years South Africa’s ruling African National Congress (ANC) has been much criticised for its proposed legislation that threatens jail sentences for whistle-blowers who expose government corruption. Its plans to set up a new state radio station which will have the exclusive task of preaching government policy have also drawn criticism.

But both of these initiatives pale in comparison to its attempt to steal an entire newspaper, Ilanga lase Natal (the Natal Sun), the Zulu tabloid newspaper which is South Africa’s oldest and biggest African-language paper.

John Dube founded Ilanga in 1903 in Durban, nine years before he became the first ANC president. He sold it in the 1930s and then the newspaper went through various owners before ending up with the Argus Group, who ran it poorly and at a loss. In 1986 Mangosuthu Buthelezi’s Inkatha movement purchased the tabloid.

Shortly afterwards Oscar Dhlomo, the Inkatha secretary-general, asked Arthur Konigkramer to edit the bi-weekly newspaper. Mr Konigkramer, who is of German descent, had been a successful local journalist, was a fluent Zulu-speaker and had successfully edited Ilanga for some years when it was Argus-owned. The United Democratic Front (an umbrella group of anti-apartheid groups) and the trade unions reacted with great hostility to this move, calling for a boycott of the paper. The paper was racked by industrial action leading, in the end, to the departure of the whole previous staff of the paper.

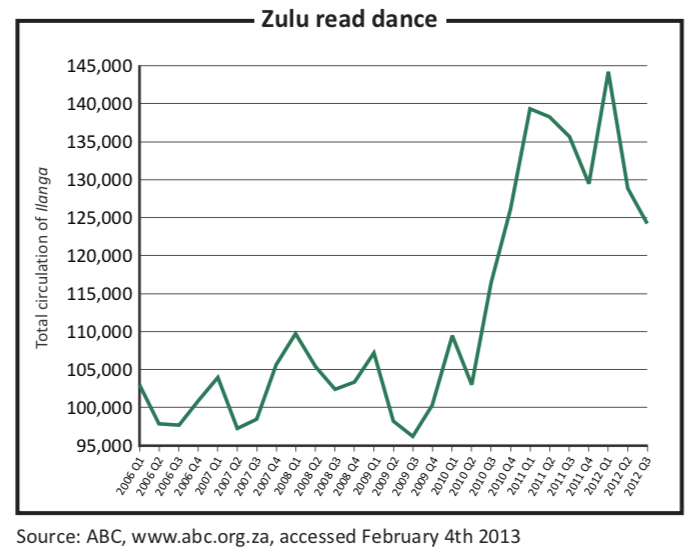

Nonetheless, within a year Mr Konigkramer had increased Ilanga’s print run from 103,000 to 143,000. By 1987–1988, the paper had almost a million readers, according to the South African Audience Research Foundation.

“The key thing was that I told Buthelezi and Oscar from the outset that I would not run Ilangaas a party paper. It had to be completely independent and show no favours to Inkatha,” Mr Konigkramer said. “We had to make Ilanga the Zulu BBC, as it were, which everyone trusted because it told the truth without fear or favour.”

Conflict raged between the ANC and Inkatha in the 1980s. The two movements quarrelled initially over Mr Buthelezi’s refusal to support armed action against apartheid. But this rapidly spiralled into an all-out power struggle. Ilanga became an inevitable target. Shops that sold Ilanga were regularly burnt down. Anyone found reading Ilanga, particularly around Johannesburg, was forced (literally) to eat it.

Despite this adversity, Ilanga prospered. The ANC then did a deal with Irish media tycoon Tony O’Reilly, allowing him to take over the old Argus Group. In return he had to set up a Zulu rival to Ilanga: Isolezwe (or Eye of the Nation in Zulu), which immediately became the chief beneficiary of ANC and government advertising.

Even this, however, failed to dislodge Ilanga from its dominant position. Isolezwehad a strong ANC bias but Ilanga could be relied on to inform its readers of all the latest details of President Jacob Zuma’s unfolding marital dramas as well as news about Inkatha that sometimes upset Mr Buthelezi. Every copy was much fingered as it was passed through innumerable hands.

In the programme for its 2012 centenary celebrations the ANC announced that one of its projects for the year would be “to reclaim Ilanga”. Already Mr Konigkramer had rebuffed several ANC attempts to buy the paper, but this plan heralded a new approach. Inevitably the ANC spent millions restoring John Dube’s house at Ohlanga in Zululand and Mr Dube’s picture was posted everywhere last year. The ANC also set up a John Dube Trust with one of Mr Dube’s grandsons, an ANC loyalist, in charge. The idea, as Senzo Mkhize, the ANC’s official spokesman, said, was that “Ilanga must come back to the correct family, the Dube family.” The only problem was, as Mr Buthelezi roundly told Africa in Fact, “Ilanga is not for sale.”

So the ANC, vastly impressed with China not just economically but politically, decided to adopt one of Beijing’s favourite tactics: mass infiltration of its opponents by agents who then disrupt, split and sabotage the movement. This technique does far more damage than straightforward opposition ever would and the ANC has used it before with deadly effect on Inkatha. In 2012, it was Ilanga’s turn.

From early 2012 the communist-aligned union Media Workers Association Of South Africa (MWASA)—an affiliate of the Congress of South African Trade Unions (Cosatu)—made a drive to enrol all of Ilanga’s journalists, many of whom had ANC loyalties. This was the prelude to a prolonged industrial war of attrition which lasted throughout last year.

At first the journalists demanded a 20% increase—which they got. The union members then demanded wage parity between whites and blacks, a nonsensical claim for all of Ilanga’semployees are black. “I soon discovered that my office was bugged,” Mr Konigkramer said, “and that anything I said there was immediately known to the ANC.”

Meanwhile, Paul Mashatile, the national minister of arts and culture, visited Durban in early 2012 and in a speech there said that Ilanga was “in the wrong hands”, something that needed to be remedied. He then hurriedly corrected himself and said, “I shouldn’t have said that,” for the ANC strategy is supposed to be secret.

Meanwhile trouble at the newspaper worsened and union activists began to commit acts of sabotage—on one occasion breaking into the paper’s offices and wiping an entire Sunday edition off the computers. Other Cosatu unions joined in and rallied their membership to boycott Ilanga. Its circulation fell from 144,000 in the first quarter of 2012 to about 129,000 in the second quarter according to the Audit Bureau of Circulations (ABC) of South Africa. At each critical juncture the Dube Trust, or some other ANC intermediary, would make a bid to buy the paper in what was, transparently, a pincer movement aimed at bringing the paper to its knees and forcing a sale at a bargain price.

But Mr Konigkramer is not a man to take on lightly. By mid-2012 he had sacked the un- ion members caught on camera committing sabotage. When other union members went on a sympathy strike, he warned them that their strike was illegal and laid them off too. “The worst thing is that these are people I’ve worked with for years and now they’re calling me a Nazi and a racist,” said Mr Konigkramer, whose office is full of Zulu memorabilia. “Damn it, I have spent almost my entire working life on a black paper, speaking Zulu and alongside Zulu people.”

The nadir was reached in October 2012 when the ANC held a meeting in Durban City Hall attended by senior party officials including the deputy speaker of the provincial legislature. At this meeting, MWASA demanded the withdrawal of all national and provincial government advertising from the paper, a blatant move to break Ilanga, according to striking Ilanga staff members who were at the meeting.

This has not happened, however, for two reasons. First, anyone who wants to recruit Africans to public sector jobs in KwaZulu-Natal needs to advertise in Ilanga. Second, the ANC seems extremely nervous that its “reclaim Ilanga” strategy may enter the public realm, for in effect it amounts to stealing a newspaper.

When I first queried the ANC’s Durban spokesman, Bongani Mthembu, he denied that the “reclaim” strategy existed—until I showed him the ANC’s printed centenary programme which details it. At that point he said I needed to ask at a more senior level.

Meanwhile, Mr Konigkramer soldiers on with the few remaining senior staff and new journalists that he is gradually recruiting. “I’ve no doubt our circulation will recover quickly—indeed the recovery has already begun,” he said. “Of course, the guys who’ve been sacked now all want their jobs back and some even try to apologise. I feel sorry for them. Many didn’t even know they were being used. But I can’t have people here who committed sabotage.”

So Ilanga soldiers on. One imagines John Dube might feel rather proud.