High commodity prices over the past decade have generated healthy profits for many companies and governments worldwide are keen to increase their cut. Zimbabwe is no exception. Tony Hawkins sounds a cautionary note on the country’s “indigenisation” approach.

Two articles in the Financial Times at the end of June 2012 set nerves jangling in African finance ministries and central banks.

The first, about the end of the commodity supercycle, coincided with reports of oversupply, falling prices and mine closures in markets as diverse as oil, diamonds, platinum and ferrochrome. The second focussed on sharply rising grain prices in the United States, the world’s largest exporter. For a continent where most countries are net food importers, this made gloomy reading at a time when its export markets were losing momentum.

The decade-long commodity supercycle since 2003, which may well not yet have ended, is mirrored in the rise of resource nationalism. From Australia to Zimbabwe, in rich as well as in developing economies, governments are seeking a bigger slice of the resource cake. For some, the solution is nationalisation; for others, minority state participation, perhaps through production contracts; for many, maybe most, it is higher taxes, especially royalties, levied on revenue not profits.

The share of state revenue in gross domestic product (GDP) in the median African state is only 20% against public spending of 28.5%. Cash-strapped African governments are always on the lookout for new sources of revenue. All the more so today: as aid budgets tighten and foreign lenders become increasingly risk averse, so the allure of oil, gas and minerals as sources of funding has grown, especially where foreign owners are reaping bumper profits.

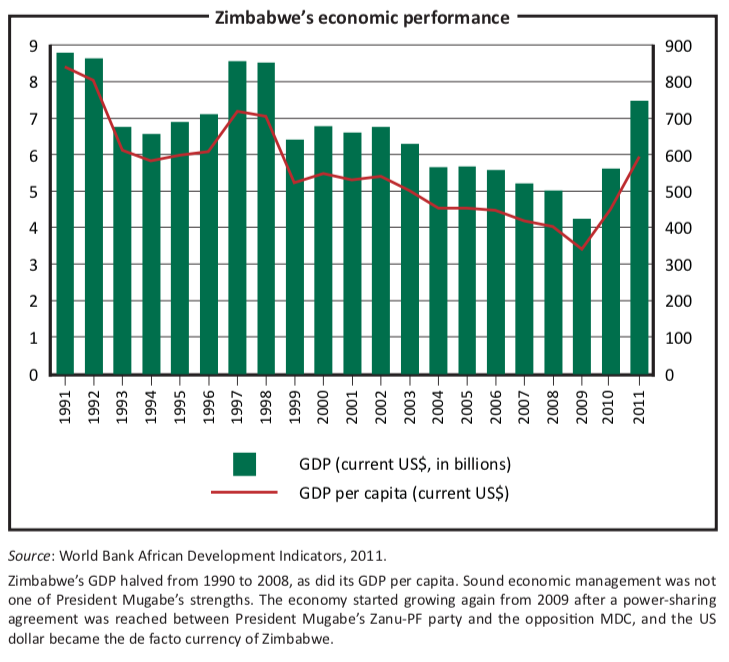

In Zimbabwe, President Robert Mugabe’s Zanu-PF party chose local ownership in the form of indigenisation, a policy wrapped up in the guise of empowerment, to appeal to voters at the polls in 2013. The Economic Empowerment and Indigenisation Act, approved by parliament in 2007 before the advent of the coalition administration in 2009, stipulates that all businesses with assets worth more than $500,000 must be 51%-owned by indigenous—for which read black—Zimbabweans.

The coalition between the two wings of the Movement for Democratic Change (MDC) and Zanu-PF is split on the policy. All three parties agree that the “principle” of indigenisation is “noble” but disagree over implementation. Mr Mugabe’s indigenisation minister, Saviour Kasukuwere, a radical firebrand, is driving the programme, so far with very little success. To date his focus has been on mining. He is demanding that all companies, regardless of asset size, implement local ownership programmes in the short term.

The programme is littered with inconsistencies. For a start, some of the country’s sharpest legal brains say it contravenes the constitution, but to date no company has had the backbone to test this in the courts. When it privatised the state-owned Ziscosteel, the government broke its own law by selling a majority stake of 54% to the Mauritian subsidiary of India’s Essar group.

The basic indigenisation “model”, as in the agreement-in-principle between the government and South Africa’s Impala Platinum group, provides for government to take a 31% stake, while 10% is owned by employees and another 10% by a community trust. In both the latter cases the shares are to be paid for out of future dividends from Zimplats, which is 87%-owned by Impala and is Zimbabwe’s largest exporter. The purchase terms for government’s 31% share are yet to be negotiated.

There are several objections to indigenisation. First and foremost, the government is facing an $830m hole in its cash budget for 2012, primarily because diamond revenues have fallen far below expectations. It simply does not have over $600m to buy 31% of Impala’s stake, never mind other foreign-owned assets.

In addition, as pointed out by David Brown, the former chief executive officer of Impala, there are practical reasons why 51% local ownership by shareholders with no or very limited resources would not work. Zimbabwe policymakers appear to believe that the 49% shareholding would provide 100% finance for exploration and development. But if indigenisation goes ahead as planned, the cost of capital will rise sharply in line with increased risk and reduced return. Capital budgets will be reduced. Output, employment, exports and economic growth will all suffer.

In the face of these objections, Minister Kasukuwere insists that the government will not pay for its own resources. He says that when the mining resource at Zimplats is valued appropriately, the country will have put in more than 31 percent of the equity. In other words, he is hoping to pay Impala for its shares by handing over mineral wealth that is vested in the state and therefore has no cash value. Impala would be exchanging shares that have a cash value on the stock market for mineral reserves that do not and for which it is paying fees to the state.

Some political and business interests are touting an alternative option: ”leverage” or “mortgage” the country’s mineral wealth by borrowing against ore reserves and using the cash to buy out the foreign owners. This assumes not only that there are financiers willing to lend to a government with a near-unparalleled track record for disregarding property rights and with a sovereign debt that far exceeds its GDP, not to mention outstanding arrears of 70% of GDP. It seems implausible, but there are those who insist that Chinese investors cannot wait to get their hands on Zimbabwe’s rich platinum, chrome, nickel, gold and diamond resources.

Then there is the empowerment argument. The proponents of indigenisation claim the policy will improve the lives of ordinary Zimbabweans. But how does state or employee ownership empower the average man or woman on the street? As with South Africa’s black economic empowerment, the process is not empowerment but cronyism.

Aside from the many financial and economic obstacles to Zanu-PF-style localisation, there is a political dimension that many believe will turn out to be decisive. The assumption is that indigenisation will be at the forefront of the 2013 election campaign during which foreign investors and owners are likely to be given a bumpy ride. But once a MDC administration, led by Morgan Tsvangirai, is securely in office, the programme will be watered down to become much more palatable.

This is probably a realistic scenario, suggesting that it makes sense for mining companies and banks that appear to be next in Mr Kasukuwere’s firing line to play for time. Again, there are snags. One is that Zanu-PF is backed by the military and security services. With direct access to diamond revenues that are not reaching the MDC-run Treasury, it might just win in 2013. It seems highly unlikely but 15 months is a very long time in politics.

The second is Mr Tsvangirai, who has underperformed since he became prime minister in February 2009. When push comes to shove after the polls, his past assurances may count for little.

Most important of all, resource nationalism is not going to disappear just because there is a change of government. The next administration will be faced with the same intractable budgetary and economic challenges as the current one. Resource wealth will be there to be exploited, yet the manner of its exploitation may change.

And so it should. “Resource curse” theory—that a country is somehow worse off because it is fortunate enough to have mineral, oil or gas wealth—arises not from resource possession but from misgovernance. It can be seen in Zanu-PF’s Wild West- style exploitation of Zimbabwe’s alluvial diamond wealth in the Chiadzwa/Marange fields in the country’s east. Zanu-PF hopes that the blend of diamond revenue and indigenisation will secure it an improbable victory at the polls in 2013. If governance were good, the curse need not arise.

The curse may overwhelm good governance when it distorts the pattern of resource allocation. Nigeria’s oil and gas wealth contributed to the country’s de- industrialisation and reliance on food imports via Dutch disease. (Dutch disease, a term first coined in 1977 by The Economist, described the impact of a North Sea gas bonanza on the Netherlands’ economy: commodity exports drove up the currency’s value, rendering other parts of the economy less competitive, leading to a current-account deficit and even greater dependence on commodities.) Booming oil exports and huge capital inflows led to an overly strong local currency. As a result, manufacturing and agriculture became uncompetitive.

Zimbabwe in 2012 is suffering a resource-curse backlash. Dollarisation, diamonds, gold and platinum have left the country with an unsustainable current account balance-of-payments deficit of 40% of GDP in 2011. Manufacturing and chunks of agriculture are simply uncompetitive. Consequently, far from moving up the value-addition ladder, the economy is becoming progressively more reliant on natural resource exports.

The preoccupation of policymakers, including those at the World Bank, the International Monetary Fund and the United Nations (UN), with immediate gains poses a severe threat to resource-rich countries. The UN has set 2015 as the deadline for reaching its millennium development goals (MDG) related to reducing poverty and other deprivations. These international bodies are therefore willing to see countries accelerate exploitation of oil or minerals if it means that the MDGs will be met sooner than later, as now looks likely.

This is a short-term view widely supported by the donor community. As a result, there is a very real danger that countries will consume their wealth, thereby leaving fewer resources for a much larger future population.

Resource-rich countries the world over have a track record of under-investing and over-consuming. Zimbabwe is no exception. To maintain and grow the country’s wealth, policymakers must ensure that when non-renewable resources such as oil or minerals are exploited, the state mobilises so-called resource rents or excess profits for reinvestment in physical and human capital. When this is not done, a country’s natural wealth declines and there is no compensatory increase in produced wealth.

The halving of poverty by 2015 is a worthy objective. But if it is to be achieved by depleting natural wealth, thereby making future generations poorer, it is a short- term fix at the expense of long-run sustainability.

Getting politicians to accept this reality is no easy task. In Zimbabwe’s case, after a decade of falling living standards, today 70% to 80% of the population lives in poverty. With elections that are likely to be bitterly contested a year or so away, quick- fix resource depletion policies are certain to win the day but unlikely to win Mr Mugabe another term as president.