Corruption in Africa

Government graft, often with the collaboration of private companies, is choking African economies

Africa is a notoriously difficult place to do business. Many investors remain sceptical of their ability to navigate the continent’s often murky operational environments, where weak governance, regulatory failure and unstructured economies have created the conditions for corruption to thrive.

The scale of graft has been particularly noteworthy in extractive industries. As a result, the citizens of many African countries rich in oil, gas and minerals are mired in poverty. Rather than investing resource revenues into infrastructure, health care and education, governments, often in collusion with the private sector, have diverted the proceeds into their own pockets.

Angola and Nigeria are plagued by the “resource curse”. They are the largest producers of oil in Africa, yet their citizens are among the world’s poorest, with approximately 70% of Angolans and 80% of Nigerians living on less than $2 a day, according to the latest World Bank figures.

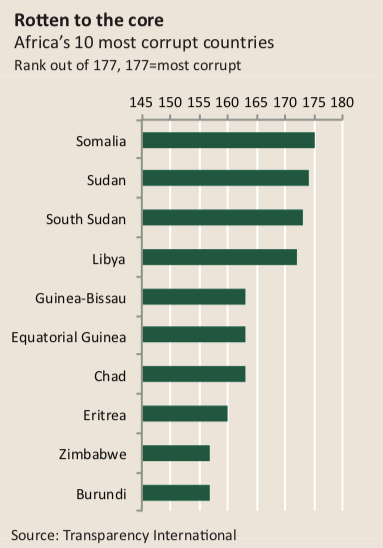

Transparency International (TI), the Berlin-based watchdog, ranked Angola a dismal 153rd out of 177 countries in its 2013 Corruption Perceptions Index. In 2012 the International Monetary Fund (IMF) reported that between 2007 and 2010 $32 billion disappeared from the country’s public accounts.

The Angolan government frequently commits itself to greater transparency, at least on paper. In 2010 it passed the Public Probity Law, which obliges all government officials to declare their wealth. This information, however, is not made public, a direct contradiction of the legislation’s title. As a result, this act has yielded few positive effects. Nigeria’s poor also suffer from the government’s mismanagement of the coun- try’s oil revenues. Unlike Norway, which has used its oil wealth to develop and diversify its economy, Nigeria is still stuck in a mono-export economy. Oil accounted for 97% of Nigerian exports between 1980 and 2010, according to a 2013 report by the United Nations Economic Commission on Africa.

Accusations of corruption have plagued successive Nigerian governments: the 2013 TI index placed Nigeria at 144 out of 177 countries. Lamido Sanusi, the former central bank governor, this year accused the Nigerian National Petroleum Company (NNPC), the state oil firm, of stealing billions from federal accounts.

This is not the first time that corruption in the NNPC has been highlighted. But Mr Sanusi’s allegations are staggering. He claims that more than $1 billion disappeared every month for a 19-month period between January 2012 and July 2013.

The Nigerian government said last March it would conduct a forensic audit of the NNPC’s books, but this has in- spired little confidence. “Even if they establish at the end of their findings that the money is missing, I am afraid that the out- come might go the way of other probes we had in the past,” said retired police commissioner Alhaji Abubakar Tsav, in a February interview published in the Vanguardnewspaper. He was referring to the fate of previous investigations, which for the most part have failed to charge or convict people and companies implicated in corruption.

Despite its prevalence, corruption is not insurmountable. Rwanda and Senegal have made substantial inroads into the scourge. Rwanda has succeeded because its president, Paul Kagame, has adopted a “zero tolerance approach” to corruption. He has backed his rhetoric with strong action when required.

In 2004 Mr Kagame created an ombudsman’s office to monitor government transparency. Four years later, on the recommendations of this office, his government suspended Janvier Murenzi, the finance director in the president’s office, pending an investigation into graft allegations. Mr Murenzi was ordered to pay a fine in excess of $1m and imprisoned for four years in 2009. “People who embezzle public funds must pay back what they have eaten,” Mr Kagame said at a 2009 press briefing.

This has helped investor perceptions: Rwanda placed 50th out of 177 countries in the 2013 TI index, a striking contrast to its fellow East African Community members: Burundi (157th), Kenya (136th), Tanzania (111th) and Uganda (140th).

Rwanda was the world’s tenth fastest-growing economy in the decade from 2000 and more than 1m Rwandans were lifted out of poverty, according to a 2013 IMF report.

Senegal provides another encouraging example. When Aminata Touré became prime minister in September 2013, she arrived with a reputation as one of the country’s strongest corruption fighters. In her prior role as justice minister, Mrs Touré had led extensive anti-corruption campaigns, prosecuting many government officials accused of corruption, including the son of Abdoulaye Wade, the former president, in April 2013.

In the 2013 Corruption Perceptions Index, Senegal jumped higher in the rankings than all but two countries in the world (Nepal and Laos), moving from 94th out of 177 in 2012 to 77th in 2013.

Institutional competence and laws can also change behaviours related to corruption. Botswana, for instance, has a functioning parliament, a robust anti-corruption commission and an independent judiciary. As a result, not only is Botswana one of Africa’s economic success stories, it is also one of the cleanest—ranked 30th out of 177 countries in TI’s 2013 index, ahead of all sub-Saharan African countries and even some developed countries such as South Korea.

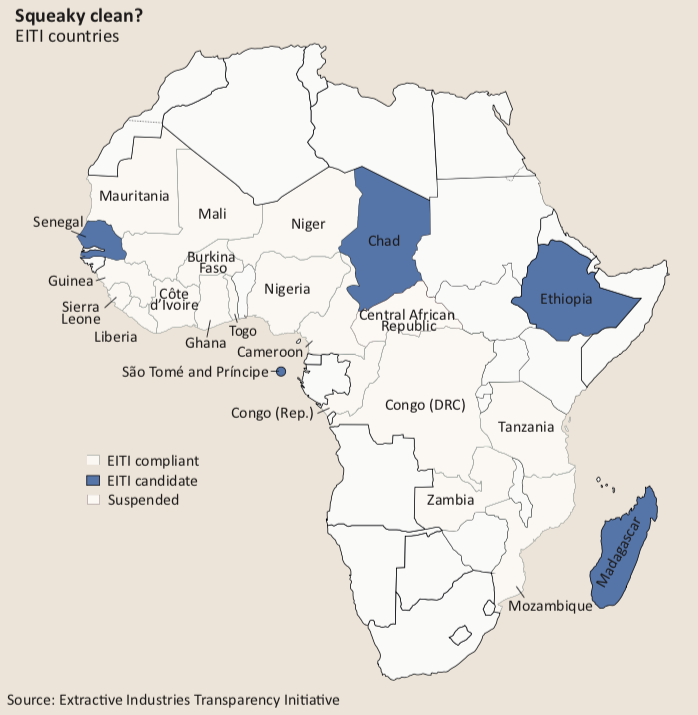

One measure that mineral-rich countries can adopt is the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (EITI). This voluntary programme seeks to promote better use of mineral wealth through increased transparency and accountability. It encourages governments and companies to publish their revenues and payments and then submit them to independent auditing. Currently 45 countries, including 22 African nations, are implementing EITI requirements and 17 are compliant, according to the EITI website.

The African Development Bank endorsed the EITI in 2006, but governments and private companies still resort to inventive ways of hiding their buyoffs and kickbacks. While the initiative in itself is not sufficient to eradicate corruption in the extractive sectors, it is generating more information on revenues that was previously either not available or difficult to access.

In addition to the EITI, African governments and multinationals need to define clearly and publicly their rules of engagement. Transparent resource management with well-defined principles and neutral administration will discourage participants from rent-seeking behaviour.

While corporate Africa’s reputation for clean business is unflattering, this is changing. As African companies strive to become world class, many are tightening up their governance, buttressing business codes of conduct and teaching their employees about ethics.

Graft is a cancer that African governments need to remove. This requires foster- ing greater transparency in their dealings with mining, oil and gas companies; develop- ing and enforcing stronger anti-corruption legislation; and creating economic policies that promote diversified, industrial economies and reduced dependency on resources.

Corruption is not simply about ethics. It is also about how a government is set up and managed. Critical elements in fighting the scourge include an active and engaged media and judiciary, and the use of information technology. The underlying causes of corruption—poor pay incentives, ineffective political processes and a deep-seated acceptance of corruption—need to be expunged. Citizens should demand greater ac- countability and transparency from their governments.

RONAK GOPALDAS is a director at Signal Risk, an exclusively African risk advisory firm. He was previously the head of country risk at Rand Merchant Bank (RMB) for a number of years, where he managed a team who provided the firm with in-depth analysis of economic, political, security and operational dynamics across sub-Saharan Africa. He holds a BCom degree in philosophy, politics and economics (PPE) and a BCom (Hons) from the University of Cape Town (UCT). He also has an MSc in finance (economic policy) through the School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS) in London.[