Malawi: infrastructure

After fifty years of ‘overlooking’ economic growth, Malawi plans to encourage public-private partnerships to fund infrastructure development

By Collins Mtika

For years, Malawi has banked on the international community for the development of its roads, factories, airports, railway lines, ICT infrastructure, water treatment plants, energy supply and even toilets. Yet despite all the assistance from organisations such as the World Bank and regional body, the Southern African Development Community (SADC), Malawi is now poorer than it was two decades ago, according to the 2016 African Social Development Index. Malawi is an extreme example, but Africa’s infrastructure deficit-estimated at $93 billion per year- is generally regarded as the single greatest obstacle to its economic development. According to the World Bank, for most African states the negative impact of deficient infrastructure is at least as large as that associated with corruption, crime, financial market and red tape constraints. The continent’s infrastructure deficit is a major constraint to doing business, depressing firm productivity by around 40%.

The bank says Africa’s weakest point is its power sector, with all of sub-Saharan Africa generating roughly the same amount of power as Spain. Only 9% of the urban population of Malawi has access to electricity, and that figure drops to 1% in rural areas, according to the National Statistics Office. Across the continent, says the International Energy Agency (IEA), only 290 million out of 915 million people have access to electricity. The number is rising because, while efforts to promote electrification are gaining momentum, they are being outpaced by population growth. Electricity generating capacity remains the greatest stumbling block to business development on the continent. World Bank figures show that the average duration of outages in hours is highest in the Republic of Congo (29.6 in 2009), with a 9.6% concomitant loss in annual sales.

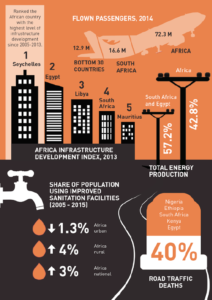

According to the IEA’s Africa Energy Outlook, supply is often unreliable, necessitating widespread and costly use of generators running on petrol or diesel. Meanwhile, electricity tariffs on the continent are, in many cases, among the highest in the world. However, reform programmes are starting to improve efficiency and bring in new capital, according to the report. The organisation predicts that grid-based generation capacity will quadruple by 2040, albeit from a very low base. Between 2000 and 2012, however, Africa increased its generating capacity by 32% as a whole (compared with a global figure of 60,5%), U.S. Energy Information Administration figures show. By 2013 electricity production was 694,000 gigawatt hours, with Egypt and South Africa contributing the bulk. Sub-Saharan Africa is also starting to unlock its renewable energy resources, and half of the projected capacity is expected to come from renewables by 2040.

The African Development Bank (AfDB) is driving an effort involving governments, the private sector, and bilateral and multilateral energy sector initiatives to develop a “Transformative Partnership on Energy for Africa”, a platform for public-private partnerships for innovative financing in Africa’s energy sector. The bank says this will require supporting African countries in strengthening energy policy, regulation and sector governance. “The New Deal will build on and further scale up the bank’s investments in the ‘soft’ infrastructure of national governments and institutions, to enhance energy policies, regulations, incentive systems, sector reforms, corporate governance, and transparency and accountability in the energy sector,” according to the bank. The government of Malawi says the country is undergoing a “silent economic paradigm shift” by trying to move from aid to trade. It aims to do so by shifting the country from its reliance on agricultural production to direct investment in multiple sectors in an attempt to stimulate a more diversified economy. “We want to address the fundamentals of economic growth, which we overlooked for the last 50 years,” President Peter Mutharika said recently.

To this end Malawi is opening up its power sector to independent power producers (IPPs), which will use nuclear, renewables, biomass, liquid fuels and coal to add about 1,550MW to the national grid by 2020. The country’s energy regulator, the Malawi Energy Regulatory Authority (Mera) says Malawi has the potential to produce 745MW to 1,670MW, based on its natural resource base of 21 million metric tons of coal, for thermal power generation, 630,000 metric tons of uranium for nuclear power and 60,000 hectares biomass which can provide an additional 50MW. The government has broken the 53-year-old monopoly of the Electricity Supply Corporation of Malawi (Escom) by offering separate sets of licences for generation, transmission and distribution. So far the country has signed memoranda of understanding with 27 IPPs.

The World Bank says regional integration of infrastructure will also lower the cost of infrastructure by giving smaller countries access to more efficient technologies and a larger scale of production. It cautions that bridging Africa’s infrastructure funding gap will require addressing the following sources of wastage: lack of timely maintenance; inefficient distribution networks; weak revenue collection; under-pricing of services; and low capital budget execution. In other areas of infrastructure development, Africa is keeping pace. The ICT sector, for instance, is closer to developments elsewhere in the world. Mobile phone subscription is extremely high at 71.2 subscribers per 100 people. International Telecommunication Union statistics show that some countries, such as the Seychelles and South Africa, average one-and-a-half phones per hundred people. Although overall Internet usage is low at 18%, some countries have extremely high penetration. Kenya is at 43.4%, up dramatically from 3.1% in 2005.

A 2015 Brookings Institute analysis says the composition of external financing for African infrastructure is changing. Overall financing across the three major external sources tripled between 2004 and 2012. During this period, while the level of Official Development Finance (aid) increased— especially from the World Bank and the AfDB—the dominance of ODF in infrastructure financing declined as private investment surged to over 50% of external financing, and China became a major bilateral source. “Viewed from a sectoral perspective, the distribution of external finance illustrates the preference and criteria of the various sources. The energy sector has had the fastest growth across all external financing sources since 2009: it now attracts 45% of the total external finance. Although private investment is significant and serves a broad range of countries, historically it has been concentrated in the telecommunications (or ICT) sector,” the report says.

Excluding telecom, private finance for other sectors, especially energy, is highly concentrated in a few countries, the report adds. “Official Chinese investments are now expanding beyond the country’s earlier focus on financing for resource-rich economies and is reaching sectors in which it has particular technical expertise—such as hydropower—and those that are not as amenable to the private sector—such as transport (especially road and rail).” While infrastructure investment as an asset class is not as high in Africa as in other parts of the world, it is on the rise. Total private investment in infrastructure in Africa between 2007 and 2014 was $305.7 million. Rwanda received the lion’s share, $86.7 million, while oil-rich South Sudan received $75.8 million, according to the World Bank’s Private Participation in Infrastructure database.

The Brookings report says sub-Saharan countries will have to raise more domestic finance. However, ultimately the quality and sustainability of infrastructure and related services resulting from increased funding will depend on the political will and capabilities of national governments. “It comes down to the broad issue of governance in which sub-Saharan countries, while progressing, still face substantial challenges,” the report concludes.