Childhood links to the motherland seem to require a certain patriotism, yet Swaziland is troubled by a self-serving ruler

From a young age I came to admire the notions of “for God and country” and, of course, “Don’t ask what your country can do for you, ask what you can do for your country.”

While the first was used to prepare men to go to war and the second— made famous by American president, John F. Kennedy—calls on everyone to focus on contributing to the building of their nation, both represent the embracing of patriotism.

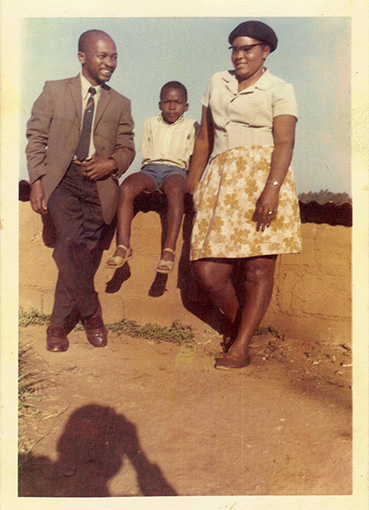

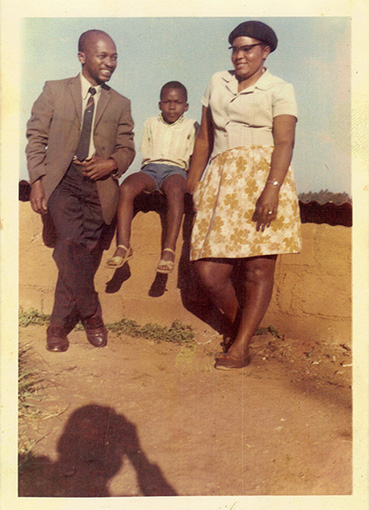

Yet they also make me feel guilty whenever someone brings up the subject of my being a Swazi. My father served as a diplomat for Swaziland at the UN and at the embassy in Washington DC. However, my mother was a South African Sotho from Barberton, where they met.

This combination—Swazi father, South African mother—has turned out to be a blessing in disguise. But it’s left me with a dilemma. Well, not just a dilemma but also a problem that has seen me battling feelings of guilt.

While my family returned to Swaziland after my father’s ten-year diplomatic posting, I remained in the States to attend varsity and I subsequently worked there too. However, when I returned in 1996, due to my father’s death, I did not return to Swaziland, but to Barberton.

So I have faced accusations of abandoning Swaziland—a country that gave me the opportunity to be educated in the “great” America. Worse yet, my American twang and associated mannerisms were a clear indication that I’d forgotten my roots. At first these comments were annoying; later I found myself asking the same questions.

It was often easy enough to ignore the comments, since they mostly came from people who were inebriated or envious of the fact that I grew up in America. The view seemed to be that I’d gone there as the son of a diplomat father, and should therefore live in the kingdom and repay my good fortune by serving it in some way. The comments always closed with: “You’re a Dlamini; a Swazi. Don’t you forget that.”

I never lost sight of or appreciation for my Swazi heritage, despite arriving in the States at the age of eight. I couldn’t have, in fact, even if I’d wanted to. We were always in the company of Swazis, whether they were in the States on business or because they were members of the royal family who were visiting for one reason or another.

Anyway, my mother would never have allowed it. She did everything to ensure my brother and I did not become too Americanised. Pap was not replaced by pizza or spaghetti. Though she did once go a bit too far, by dressing my siblings and me in shorts on our first day of school.

This gave our new schoolmates the opportunity to introduce us to the sensation of snowballs pummelling our exposed legs. (We arrived in New York one early November.)

There were also the mandatory holidays back home every three or four years—which were intended to give the foreign affairs contingent the opportunity to personally brief the king on their work and progress in the US. I remember my father saying that these trips were not just holidays or compulsory briefing sessions: His Majesty King Sobhuza II had insisted on them, to ensure that the family, more especially the children, did not lose touch with their Swazi heritage.

So I never really turned my back on my Swazi background then. The same questions sometimes come up, however, in this part of my life, because I’ve chosen to settle just across the border in Barberton. In fact, it doesn’t really feel as if it isn’t Swaziland. The population of this little mining town, and indeed a good portion of Mpumalanga, is predominantly Swazi, with all that comes with that: language, culture and traditions.

Choosing to stay in Barberton on my return in 1996 had more to do with the desire to be in the wider environment offered by South Africa, with its bigger economy, and cultures and languages, rather than the small environment represented by the tiny kingdom.

Many of my Swazi compatriots prefer to come to South Africa, seeking greener pastures. They range from professionals to illegal miners. All the same, most remain fiercely loyal not only to the “motherland” but also to the monarchy—despite the widely publicised excesses of the current monarch, King Mswati III.

This is why I see my being born in South Africa as something of a blessing. My fellow Swazis, who are often in South Africa without work permits, must return to the kingdom at the end of every month because of the 30-day entry limitation imposed by South African immigration authorities. Needless to say, I’m glad I’m spared this.

Heritage aside, what do I feel about my “motherland”? Well, as one of my professors at varsity said: “How you feel and what role you play in the society you live in must be determined by your understanding of its social, economic and political realities.”

I have to say that the current monarch, and particularly his effect on the kingdom’s economy, doesn’t inspire much patriotism.

This is a view I share with many fellow Swazis. Our catch-22 reality is that, while most of us, including myself, fully support our monarchical heritage, we have been let down by the sitting king.

When my father’s diplomatic stint ended in 1983 he was appointed principal secretary of foreign affairs. In that position he had regular interactions with King Mswati, who was crowned in 1986. When he got to know the king better he commented to my mother one day: “Under this boy Swaziland is in trouble. All he seems to care about are the benefits of being king.” Sadly, my father’s observation has come true.