Gabon: 50 Years of the Bongo Dynasty: A Tale of Power, Corruption, and Fall. By Gerome Rousseyon and Stephanie Blachart

In Gabon: 50 Years of the Bongo Dynasty: A Tale of Power, Corruption, and Fall, Gerome Rousseyon takes an in-depth look at the Bongo family and their time in power for over half a century, establishing a political dynasty marred by corruption and human rights abuses.

Although the reign of the Bongo dynasty was characterised by a long period of uninterrupted power, the author also analyses in great detail the tumultuous journeys of key political figures who influenced Gabon’s trajectory.

Of particular significance was a prominent politician who rose to power in the wake of Gabon’s independence from France, namely Léon M’ba.

Born in 1902 in Libreville, Gabon, Léon M’ba founded the Gabonese Democratic Party, Parti Démocratique Gabonais (PDG) in 1957 upon his return from exile. With a key focus on national unity, education, and the promotion of Gabonese traditional values, the PDG quickly gained popularity.

Upon attaining independence on 17 August 1960, M’ba became the first president of the Gabonese republic. Under his rule, Gabon embarked on a path of economic development fuelled by its abundant resources, particularly oil.

Regrettably, Léon M’ba’s time in office was tainted by accusations of corruption and nepotism, while others believed his authoritarian style hindered Gabon’s nascent democracy. The divergent views regarding his leadership style escalated political tensions and drove Gabon into political turbulence. It was during this period (in 1966), that the Chief of Staff of the armed forces, Albert Bernard Bongo, gained political prominence.

At the height of Bongo’s popularity, Léon M’ba succumbed to cancer that claimed his life on 28 November 1967, further raising concerns regarding presidential succession.

Amid uncertainty, and with political clout in his favour, Bongo seized control through a military coup, asserting that it was the wish of the late president.

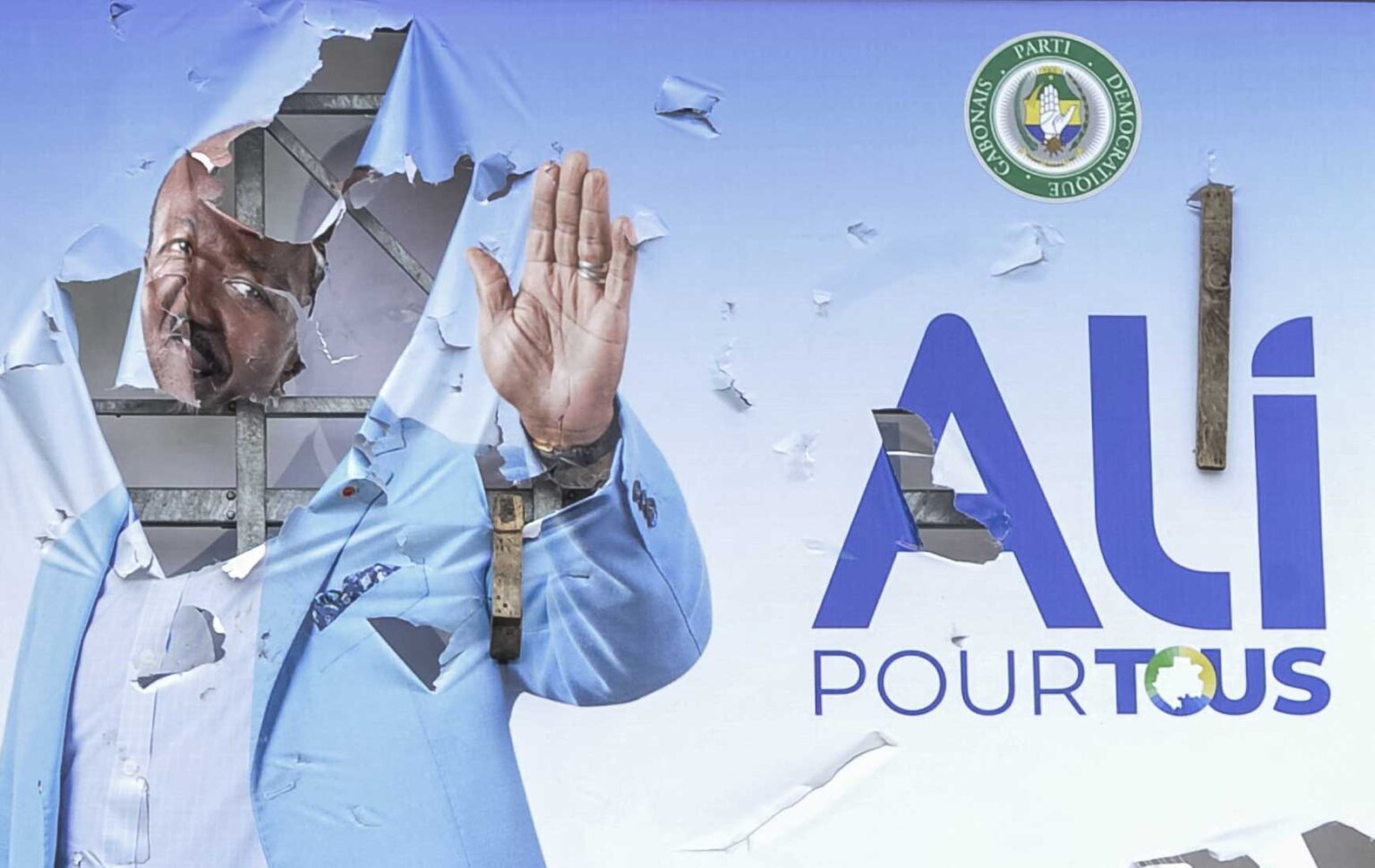

Bongo, who then renamed himself Omar Bongo Ondimba after converting to Islam, became president in 1968 and ruled the country until he died in 2009. His son, Ali Bongo Ondimba, succeeded him after a contested election, ruled for 14 years, and was ousted from power through a military coup on 30 August 2023.

Though his rise to power remains controversial due to allegations of electoral fraud and contested elections in 2009 and 2016, Rousseyon stresses that Ali Bongo attempted to diversify Gabon’s economy and reduce its reliance on oil. He also sought to implement economic and political reforms, including launching the Strategic Plan for an Engineering Gabon (PSGE) to diversify its economy.

Political events featured in the book reveal that the nature of Gabon’s political journey – from its independence in 1960 to when civil war erupted in 1967 – set in motion a recurring political cycle that shaped the destiny of Gabon under the Bongo dynasty. Notwithstanding that, the majority of political events that occurred were not without the influence of outside forces, in particular France.

Once in power, Omar Bongo established a single-party regime, which marked the beginning of the PDG’s political dominance, where opposition parties were marginalised and their leaders forced into exile.

Suffice it to say, from 1968 to 1990, Gabon thrived economically due to its natural resources, specifically oil, forestry, and mining, albeit with the cooperation of France, which maintained close relations via bilateral agreements that ensured its continued access to Gabon’s natural resources.

Regrettably, due to dissension among citizens, from 1990 to 1993, Gabon witnessed social and political unrest, dubbed by the author as the “fiery years”.

In a move towards democracy and to pacify citizens, Omar Bongo restored the multi-party system. Opposition members joined the government, and new political parties emerged. Despite the reforms, in December 1993 Omar Bongo got reelected in the first multi-party presidential elections. The opposition contested the electoral process, which led to violence and the subsequent intervention via the Paris Accords to ease tensions.

Nonetheless, nothing changed as Omar Bongo got reelected each election season, and consistently, election results were contested each election year for alleged irregularities – until he died in 2009.

The future of Gabon remained unclear at the time of Omar Bongo’s death. Although the Gabonese people anticipated that the fall of the Bongo dictatorship would bring democracy and wealth, there were too many obstacles to overcome. Decades of authoritarianism and corruption left the nation with unresolved issues relating to social justice, income redistribution, and transparent governance.

The Elf Affair (late 1980s and early 1990s, which took eight years to go to trial in France) and the more recent Ill-Gotten Gains (IGG) cases are notable examples covered in the book, that illustrate the corruption that characterised the Bongo regime.

When former executives of a French oil corporation, Elf Aquitaine (now known as Total Energies), and FIBA (a French intercontinental bank), faced accusations of embezzlement and other illegal activities, evidence came to light implicating Omar Bongo.

He was implicated in signing paperwork facilitating Andre Tarallo, a pivotal figure in the Elf Affair, to embezzle funds. Specifically, and as featured in the book, Tarallo was accused of participating in a vast system of corruption and kickbacks, contributing to the financing of the French political elite, allied African regimes, and personal bank accounts. Tarallo was a key player in what is, to date, one of the largest corruption scandals in French history. Despite the grave charges against Omar Bongo, he repeatedly denied involvement in the Elf Affair.

The payments made to the Francophone regimes were partially aimed at guaranteeing that Elf Aquitaine maintained sole access to oil in Gabon and ensured that the Francophone African leaders kept their allegiance to France.

Comparably, the Ill-Gotten Gains Cases (IGG) are a convoluted affair, still going through the French courts, in which African heads of state and their families were charged with illegally acquiring movable and immovable property, mostly overseas, through misappropriating public funds. Key individuals involved in this case include the following presidents and their families: Omar Bongo Ondimba (Gabon), Denis Sassou Nguesso (Republic of the Congo), Teodoro Obiang, and his son Teodoro Nguema Obiang Mangue (Equatorial Guinea).

Nine of Omar Bongo’s children were also implicated and charged with money laundering, improper use of company assets, active and passive corruption, and misappropriation of public funds. Among them was Pascaline Bongo Ondimba, his eldest daughter, who had previously served as her father’s Chief of Staff and Minister of Foreign Affairs.

Undoubtedly, the Bongo reign left an indelible mark on Gabon, a country rich in resources but impoverished by decades of misrule. The absorbing, albeit worrisome, saga of money, power, and dictatorship has sparked ongoing debate regarding the complex dynamics between foreign powers and African politicians.

Rousseyon does an exceptional job of detailing Gabon’s history and the impact of the Bongp dynasty on both Gabon and central Africa. His assessment of the military and political figures who influenced Gabon’s political and economic landscape allows readers to fully comprehend the far-reaching consequences of corruption and how countries can get stuck in ceaseless cycles of coup d’états.

General Brice Oligui Nguema is currently Gabon’s Transitional President, and he has promised to return power to civilians after the transition, although the duration and specifics of execution remain unclear.

Despite key opposition leader Albert Ondo Ossa’s initial support for the coup in August last year, he is sceptical about Gabon’s political future, fearing that the Bongo clan may still be in control behind the façade of civilian rule; General Brice Oligui Nguema is a cousin to the Bongo family.

Irrefutably, Gabon represents many of the complexities of contemporary Africa. The political history serves as a powerful warning that even the most resilient dynasties are doomed to fall when vested interests and corruption take precedence over the welfare of a country.

This book is suitable for economists, historians, governance specialists, and political analysts who study the impact of neo-colonialism, transitions of power, and the quest for democracy in countries still grappling to allow for fair play in multi-party systems.

Sarah Nyengerai is an academic and freelance writer based in Zimbabwe with a strong passion for social, cultural, economic and political issues that affect women. She believes literary works form the foundation for the dialogue required to sustain momentums of change and aims to bring attention to such matters. A member of NAFSA (Association for International Educators) and Forum for African Women Educationalists (FAWE), Sarah is actively involved in the advancement of education for women.