Brazil is one of the world’s leading food-producing nations, topping global export charts for coffee, soy and sugar. Agriculture accounts for about 30% of this South American country’s GDP. It has been a force in the emergence of Brazil’s economy onto the world stage. Now Brazilians are turning their attention to Africa.

by Louise Redvers

Brazilian Marcos Brandalise was an aviation operations manager when he first flew over Africa’s vast uninhabited countryside in the 1980s. He was based initially in Angola and then later in Kenya where he had his first glimpse of Africa’s untapped agricultural potential.

After the airline job ended he stayed on in Kenya. In 1996 Mr Brandalise, 53, set up his own business, BrazAfrica Enterprises Ltd, which imports, among other items, Brazilian agri-processing equipment for coffee and other grains into Africa. The company’s annual group turnover is currently $16m but the firm is aiming for $50m by 2016.

“From my experience of the continent I could see there was this huge need to bring in modern equipment,” Mr Brandalise explained. “Suppliers from Europe and the United States were too first-world, too high-tech for the African context and largely too expensive. In Brazil we had learnt how to adapt this high-tech processing equipment to the needs of smaller farms and co-operatives so I applied those solutions to the African market, which in many ways is similar.”

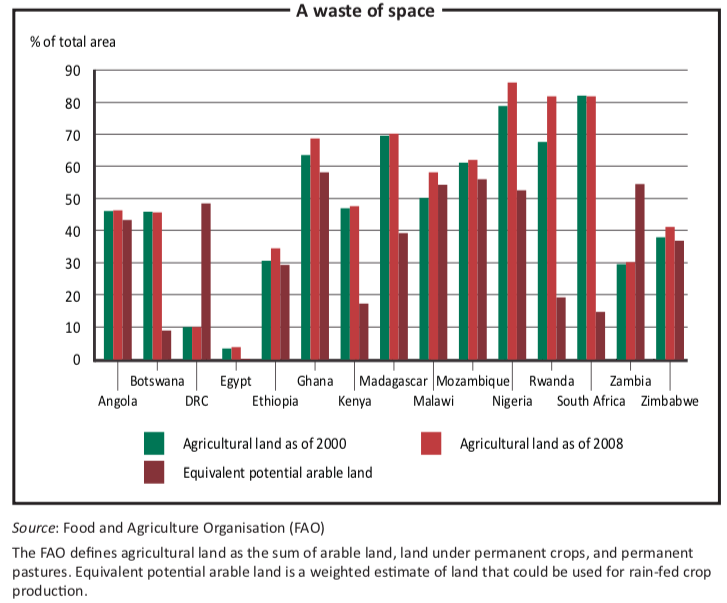

Besides its headquarters in Kenya’s capital of Nairobi, BrazAfrica now has branches in Ethiopia, Mozambique, Rwanda, Tanzania and Uganda. It is one of a growing number of Brazilian outfits operating across the continent. They have come to recognise that Africa, blessed with millions of hectares of arable and grazing land, remains highly food-insecure. The continent offers investors great potential to increase agricultural production while making a profit.

Not only has Mr Brandalise discovered this, but so has his native country. Brazil has managed to turn its agricultural sector into a world force through a combination of intensive farming techniques, fixed-pricing policies and the creation of co-operatives, as well as easy credit and market access for smallholders. Now the world’s sixth largest economy, Brazil’s exports have increased by more than 400% in the last decade, according to its ministry of agriculture.

Africa is a natural fit for Brazil in terms of agriculture and the development of agri-business, said Edward George, head of soft commodities research at Ecobank Capital, the capital markets and investment banking arm of the Togo-based but increasingly pan-African bank.

Soft commodities—coffee, corn (maize), fruit, sugar, etc.—are grown rather than mined. “Brazil is one of the world’s leading soft commodity producers and they are already doing a lot of trade with Africa in terms of exporting items like sugar and rice,” he explained. The world’s second largest sugar refinery in Lagos, Nigeria, is supplied entirely by raw Brazilian product, he added.

“It makes sense that given their own [Brazilian] economy is slowing, that they start to look for new markets elsewhere. And with their expertise in products like sugar and soy, and experience of working in tropical climates with smallholder farmers, they have a lot to offer Africa.”

A four-hour drive east of Angola’s capital Luanda leads to the Capanda Agro- industrial zone in Malange province. The 410,000-hectare site sits on the banks of the Kwanza River and a recently-rehabilitated railway line links it to Luanda. It is the centrepiece of a government strategy to revitalise Angola’s once-lucrative farming sector. Decades of civil war have left the country highly food-insecure and dependent on expensive imports. Attempts to relaunch local production have had mixed results.

State entity SODEPAC (Sociedade de Desenvolvimento do Pólo Agro-Industrial de Capanda) manages the site. It has carved it up into concessions to be run by public– private partnerships in all disciplines of crop and livestock farming and agri-business processing.

One of the first companies to sign up was Bioenergy Company of Angola (BIOCOM), which has planted 30,000 hectares of sugar cane. It is in the final stages of building a processing factory that will produce bio-diesel ethanol for domestic industrial use and sugar, ending Angola’s reliance on imported sugar. In addition, the firm will also burn the biomass from the sugar production and convert it into electricity for the local grid.

BIOCOM is a joint venture between Angola’s state oil company Sonangol, a group of private Angolan investors and Brazilian civil engineering conglomerate Odebrecht, which through its subsidiary ETH Bioenergia, is one of Brazil’s leading sugar and bio-diesel producers.

A mixed Brazilian-Angolan team has designed the factory, which is expected to begin operating in late 2013. As part of the venture, a number of the Angolan staff has spent time in Brazil learning about sugarcane cultivation and post-crop processing techniques.

African agriculture provides many opportunities for Brazil, said Gilmar Henz, Brazil’s first agricultural attaché in Africa, and one of only eight globally. “Brazil has an excellent record in agriculture and it is a key sector in our economy,” he said. “We have expertise we can share with Africa and similar conditions in terms of soil, climate and the high proportion of smallholders.

“Operating in Africa also opens doors to exports to the European and US [United States] markets,” he added, through schemes such as the African Growth and Opportunity Act, which gives exports from some African countries duty and quota-free access to the US market.

“I know that there is growing interest among Brazilian farmers to move to

Africa though there are concerns about land ownership and political stability which need to be overcome,” Mr Henz said in a cautionary tone.

The force behind much of Brazil’s agricultural achievement is the Brazilian Agricultural Research Corporation (EMBRAPA). The country’s then military dic- tatorship created this agency in 1973 to nationalise agriculture and control food security issues. Since then, it has evolved into a world-renowned centre of expertise and research.

It was the force behind the development of the 270m-hectare cerrado, Brazil’s savannah in the centre of the country. This was once just a vast swathe of dry bush, deemed unfit for anything. But the cerrado is now—thanks to the application of various adapted techniques of sowing and tilling, cultivation of specific crop species and intense irrigation schemes— the source of much of the country’s food, cash crops and livestock exports, particularly soya and cattle.

Although controversial in the eyes of some environmentalists who are concerned about land claims, monocultures, water diversion and the unregulated use of pesticides, the cerrado has been at the heart of Brazil’s green revolution.

The first EMBRAPA Africa office opened in Ghana in 2006, under the presidency of Luiz Inácio “Lula” da Silva, who placed both Africa and agriculture firmly at the centre of his economic plan.

Since then EMBRAPA has given technical support to over a dozen African countries—including Angola, Benin, Burkina Faso, Chad, Mali, Mozambique and Senegal—in a variety of areas from rice growing and cotton cultivation to animal husbandry and bio-diesel capacity building.An EMBRAPA spokesman stressed that the Brazilian research unit offers technical support as opposed to direct investments in farming projects. The funding is provided by the Agency for Brazilian Co-operation (linked to the Brazilian ministry of foreign affairs), host country governments

and agricultural institutions, and other international aid programmes, like the United States Agency for International Development (USAID).

EMBRAPA’s reach and the tech- nical benefits delivered have created a good platform for private Brazilian companies to enter the African market. Brazil receives little of the backlash felt by its emerging- economy competitor China, which is regularly accused of trying to re-colonise Africa for its own ends through land grabs.

“Brazilians are warm people and we are always welcomed in Africa, where there is a sense of shared culture because of [our] share[d] history back to the days of slavery,” Mr Brandalise said. “We have a lot in common and I think people appreciate that Brazil has a model of agriculture to share with Africa, whereas China doesn’t have a tried and proven model as such.”

Mr Henz, who is based at Brazil’s embassy in South Africa, agreed that Brazilians were more generally welcome than the Chinese. He blamed this antipathy on the Chinese trend to import labour rather than employing locals. An agronomist by training, Mr Henz recalled his own experience of being trained by the Japanese International Co-ordination Agency in the 1970s. It is now Brazil’s turn to share its skills, he added.

“We have been a third-world country but now we are somewhere in the middle,” he said. “This makes us closer to Africa and in terms of Africa, we are ahead of them but closer than say Europe or the United States, or Japan. This engagement is about the changing Brazil and where we are in the world,” he said.

[author] [author_image timthumb=’on’][/author_image] [author_info]Louise Redvers is a freelance journalist based in Johannesburg, South Africa. She reports from Angola, Swaziland and Zambia for the BBC, the Mail & Guardian, The Africa Report, the Economist Intelligence Unit and Monocle. [/author_info] [/author]