ANGOLA: Front for the Liberation of the Enclave of Cabinda

Can an overseas stock market help FLEC on the road to Cabindan independence, or is this latest move yet another sign of a fractured and dying struggle?

by Louise Redvers

Resources have long been the source of conflict in Africa. Battles for control of resource-rich territories take many shapes and—often devastating to people on the ground—are waged on many fronts. Now separatists in Angola’s oil-rich province of Cabinda have turned to stock markets overseas to fund their struggle by selling rights to future mineral assets they hope to own one day.

Kilimanjaro Capital, incorporated in Belize, based in Calgary, Canada, and listed on the GXG stock exchange in Denmark, offers the chance to invest in lucrative oil and mineral concessions in Cabinda, an area of some 8,000 square kilometres that is separated from the rest of Angola by a narrow strip of the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC). Cabinda—with a population of 500,000—is home to some of Angola’s most productive on- and offshore oil blocks, producing between 500,000 and 700,000 barrels of crude oil per day—a third of Angola’s lucrative export.

These so-called “future contingent licences” are being marketed on the back of a legal claim that members of Cabinda’s 50-year-old separatist movement, the Front for the Liberation of the Enclave of Cabinda(FLEC), submitted to the African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights (ACHPR) in Gambia in 2006. The ACHPR, with characteristic indecisiveness, has yet to make a ruling on FLEC’s claim.

FLEC is one of Africa’s oldest separatist movements. Formed in 1963, it claims independence for Cabinda based on the 1885 Treaty of Simulambuco, which gave the enclave the status of a Portuguese protectorate.

Five decades later, that claim still stands, and even if they do not express it publicly for fear of reprisals, the majority of Cabinda’s inhabitants support the claim. Cabindans are not just geographically but also, many would argue, culturally closer to neighbouring DRC and the Republic of Congo than they are to the rest of Angola. They even have their own language, called Fiote, which they speak in addition to Portuguese.

Jonathan Levy, the Washington, DC-based lawyer representing Kilimanjaro Capital’s African clients, is unfazed by the ACHPR’s indecisiveness. He told Africa in Factthat merely by accepting jurisdiction of the case, the court set an important legal precedent for other secessionist groups seeking claims over resources in their territories. Mr Levy says he believes a ruling may come in 2014, and is—some might say predictably—confident of a positive outcome.

Although some have been more than a little sceptical about Kilimanjaro Capital since it appeared on the scene last year, Mr Levy, who also helped set up the Organisation of Emerging African States (something he describes as a “virtual forum to help secessionist groups network and share ideas”), denied that the firm was illegal or fraudulent in any way. “Nobody is trying to pull the wool over anybody’s eyes because it’s fully transparent and it’s very clear what it is,” he says. “It would be difficult to think that you were buying licenses that were actually functional: that’s why they are called future contingent licenses.

“It’s certainly a gamble, yes, but essentially with all junior oil and mining companies you’ve got to gamble. In many cases you can spend several million dollars to punch some holes in the ground and find nothing, but in this case, you are investing where we know resources exist, so we know what’s below the ground. It’s just what’s above ground that needs to change,” says Mr Levy, whose other clients include a religious movement suing the Vatican based on claims that extra-terrestrials founded the human race.

Mr Levy admitted that Kilimanjaro Capital was generating income for FLEC and other movements, but denied this was funding or encouraging violence. “There were concerns when we were setting up that the money could be used for other things,” he explains. “But we’re not handing over money unless we’re sure about where it’s going. We are supporting specific activities for these groups like legal, diplomatic, education, humanitarian efforts as well as cultural events, not violence.”

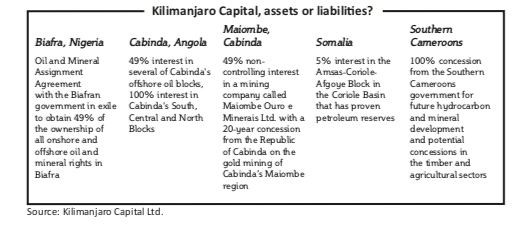

Kilimanjaro also offers stakes in mineral assets in Cameroon and Nigeria and says it has recently been awarded an oil block in Somalia.

Yet despite such bold claims, its slick website, a London-based PR outfit and trading updates, there is one problem with Kilimanjaro Capital: FLEC.

FLEC is today a faint shadow of the one-time muscled guerrilla movement that controlled, some estimated, as much as 70% of the province, helped by international sympathies and financial support.

FLEC has always been a fractious movement, characterised by splits since its inception. Today there are no fewer than four separate FLEC factions, whose various exiled leaderships are scattered across Europe. There is disagreement over who is in charge of the troops on the ground and, indeed, how many soldiers are even left. Estimates range from just 200 to 2,000.

While a group calling itself the Front for the Liberation of the Enclave of Cabinda – Military Position (FLEC-PM) apparently claimed responsibility for theattack on Togo’s national football team in Cabinda during the African Cup of Nations in January 2010, doubt remains, even within FLEC itself, over who in fact was behind it. The shooting, in which at least three people were killed, scored FLEC global headlines with an English Premiership player among the survivors.

FLEC-PM is led by former baggage handler Rodrigues Mingas. Soon after the shooting, at the request of the Angolan authorities, Mr Mingas was detained in France, where he was living at the time, on suspicion of “criminal conspiracy in relation with a terrorist enterprise”. He was never eventually charged.

The FLEC faction aligned to Nzita Henriques Tiago, one of the movement’s original founders, was initially blamed for the ambush. However, Mr Tiago’s spokesman, Osvaldo Franque Buela, who lives in France, denied this and told Africa in Factthat the Angolan government orchestrated the attack in a bid to stain FLEC’s reputation. FLEC was committed to a peaceful resolution to the conflict, he says.

Based in Paris, and now in his 80s, Mr Tiago heads what is known as FLEC FAC (Forças Armadas Cabinda). This group was formed in the 1980s as an offshoot of the original FLEC. In recent years, Mr Tiago has publicly called for negotiation with the government.

In August 2010 Mr Tiago’s then chief of staff, Alexandre Tati, and Stanislas Boma, then vice-president, reportedly unhappy about Mr Tiago’s attempts to talk with the Angolan government, challenged the FLEC FAC leadership. Soon afterwards, they announced on Voz da Américaradio that Mr Tati had taken over the leadership of FLEC from Mr Tiago, which the latter denied. Mr Tati and Mr Boma then broke away and formed a small splinter group known informally as “FLEC de Tati”. Based in between the Republic of Congo and Cabinda, Mr Tati and Mr Boma are the leaders most commonly linked to fighters on the ground.

Eight months before they left, there had been another breakaway from FLEC FAC. The group’s former secretary general, Joel Batila, along with Afonso Massanga, who was formerly with the National Union for the Liberation of the Enclave in Cabinda (UNALAC), have since named themselves prime minister and president of the Republic of Kabinda (sic).

It is Messrs Massanga and Batila who are involved with Mr Levy and Kilimanjaro Capital. Mr Batila, also long in exile, is a member of the investment fund’s four-man advisory panel.

Mr Levy says he has been FLEC’s counsel since 2006, although he admits he has never met Mr Tiago. Messrs Batila and Massanga did not believe that FLEC carried out the Togo team shooting, according to Mr Levy, but left Mr Tiago’s group because “they didn’t want to associate with someone who wrongly, through incompetence, was associated with terrorism.” He added that the two men had no intention of negotiating with the Angolan government. “Dr Batila and Mr Massanga are involved in a civil, not a military, operation. It is an economic warfare and a different front of the struggle,” Mr Levy says.

Asked what would happen should the ACHPR rule in FLEC’s favour and award them the oil and mineral concessions they are claiming, Mr Levy says it would be up to FLEC’s members to sort it out among themselves. Given the deep divisions among FLEC’s various leadership groups, this would seem just as unlikely to happen as the court making the award in the first place.

There are some who believe FLEC is fading away altogether. According to one Angolan journalist who has reported on the struggle for several years, many people, including Mr Tiago’s children, are waiting for him to die so they can negotiate a settlement with the Angolan government.

This is not an entirely unfeasible scenario. “One of the reasons FLEC is fragmenting is that its members are being co-opted by the government,” says Markus Weimer, an expert on Angola and London-based senior analyst at Control Risks Group, a consultancy. It is relatively common for opponents of the government, whether from FLEC or UNITA, to relinquish their position in return for a post in the ruling MPLA, perhaps something high-ranking in the police or armed forces.“For many, faced with declining military fortunes and the threat of elimination by the Angolan army, this may be increasingly attractive,” Mr Weimer says.

Several high-ranking FLEC members have already jumped ship. Antonio Bento Bembe, who was leading a faction called FLEC Renovada (or Renewed in Portuguese),signed a memorandum of understanding with the government in 2006. In return, he was made minister for human rights, despite having been subject to an international arrest warrant for his part in the alleged kidnapping of a foreign oil worker. Mr Bembe has since been demoted to secretary of state for human rights and is seen as a largely sidelined figure.

This memorandum was claimed as a peace deal, but Mr Tiago’s faction did not accept it. Guerrilla attacks continued, although Angola’s tightly-controlled media reported few of them andthe world was led to believe the struggle was over.

In 2009, in the months before Angola hosted the fateful African Cup of Nations soccer tournament, Mr Bembe boasted to international media that FLEC no longer existed.

In response to the attack on the Togo footballers, the Angolan authorities, who have long employed a web of secret police in the province, where civil society activists and journalists are regularly arrested, stepped up their surveillance—detaining four human rights defenders, among them a lawyer and a Catholic priest.

The court convicted this group of committing crimes against state security, a murky charge related to dialogue they had had with FLEC members in Europe some years earlier. After almost a year in custody, however, they were acquitted on a technical appeal that claimed the legislation used to convict them was out of date.

Two other men were arrested for the attack. Only one was convicted, however, and sentenced to 24 years in prison.

The 2010 shooting gave Angola’s army, the Forças Armadas Angolanas (FAA), the green light to raise its response to FLEC. Throughout 2010 and 2011 troops carried out raids into Cabinda’s dense northern forest territory and even across the borders into the DRC and Republic of Congo, where FLEC has historically received support.

During these raids, the FAA recovered scores of FLEC guerrilla fighters from the bush camps there. They were “demobilised” and “rehabilitated”, and paraded in front of the state media, condemning FLEC and its violent ways. A number of well-known military commanders were also reported to have been killing during this period, their deaths also glorified by the country’s government mouthpiece Jornal de Angola.

Raul Danda, a former member of civil society movement Mpalabanda, which was set up in 2004 to promote dialogue about independence issues but later banned for its alleged links to FLEC, denies that FLEC is a spent force. “Yes, there are people who have been killed, but there are still many left,” he says. “If there was no military threat from FLEC anymore, why would there be so many FAA soldiers in Cabinda? They have to be there for something. You don’t throw stones into a tree unless it contains fruit.”

Mr Danda is a university lecturer and member of parliament for UNITA, Angola’s main opposition party. Although he continues to call for negotiations about Cabinda’s future, he dismisses Kilimanjaro Capital as an authentic part of FLEC’s struggle. “I don’t know what Batila is doing but he is not part of FLEC,” Mr Danda says.

Mr Danda was at pains to stress that FLEC’s demands are not simply about securing the bounty of the enclave’s natural resources. “It is very unfortunate that when the international community looks at Angola, it only sees oil,” he says. “For me, this is not about oil, nor is it a military problem: it’s about aspiration. What FLEC wants is independence and that is shared by all the people of Cabinda. If there was a referendum tomorrow [on secession], everyone would vote yes.”

Control Risks Group’s Mr Weimer, however, is cautious about completely discounting Kilimanjaro. “There is no chance that Angola will ever allow FLEC to have control of mineral rights, but Kilimanjaro is certainly a very interesting development because it’s something external and outside the control of the Angolan government,” he says. “What it is doing is giving FLEC international exposure and creating an alternative reality that is going to put new pressure on the Angolan government; so we must see how they respond.”