Nigeria: behind Abuja’s facade

Locals displaced by the creation of Nigeria’s capital are still waiting for just compensation

Abuja, Nigeria’s capital, is one of Africa’s most expensive cities to live in, according to a 2013 Economist Intelligence Unit report. But behind its expansive roads and upscale neighbourhoods housing Nigeria’s rich and powerful, Abuja is home to some of Nigeria’s poorest slums.

These shanty communities—tucked in between gleaming mansions and office blocks—are the face of a four decades old land rights controversy pitting the government against a dozen small ethnic groups that were living in the area when the capital was created in 1976.

Modern-day Abuja grew out of Nigeria’s bloody civil war between 1967 and 1970. Six years after the conflict ended, the country’s military ruler, Murtala Mohammed, pushed for a new capital he hoped would promote national unity. His government chose Abuja because it was in the centre of the country and had no clear majority ethnic group, such as the Yoruba in Lagos, Nigeria’s most populous city and the capital at the time.

Mr Mohammed’s 1976 military decree handed ownership of Abuja’s 8,000 square kilometres of land to the federal government and pledged to compensate and resettle the displaced indigenous populations before beginning Abuja’s development.

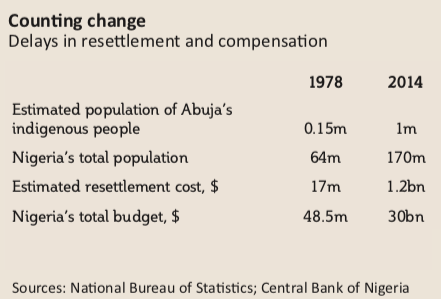

Nearly 40 years later, no Nigerian administration has either fully resettled or compensated Abuja’s original inhabitants—a result of policy flip-flops, legal inconsistencies and corruption. Today about 1m indigenous residents and their descendants live in Abuja, according to estimates from the Original Inhabitants Development Association (OIDA), an Abuja-based activist alliance.

The prolonged failure has resulted in two categories of indigenous Abuja communities: those resettled by the government in satellite cities around the capital without full compensation, and those who remain in the slums behind Abuja’s polished façades.

Kutako is one such neighbourhood. Surrounded by the posh apartments of the upmarket Utako district, Kutako is home to about 650 original Abuja residents, some living in mud houses with thatched roofs, others in shacks capped by zinc sheets.

Ladi Auta, a 61-year-old farmer with nine children, lives in Kutako and shares a three-room cement-coated mud house with her husband and nine children. The state took her family’s land in 1976 and has refused to give them a new home and farmland as promised. In 2006 city officials arrived at the settlement to count residents for possible relocation. “Since then, we have not heard anything,” she said.

Eleven successive governments have failed to comprehensively address the resettlement and compensation of Abuja’s indigenes, creating a convoluted web of lawsuits and controversy. Nigeria’s minister for the Federal Capital Territory (FCT), Bala Mohammed, said in March that the government needs $1.2 billion to address all the accumulated claims dating back to 1976.

The trouble began with the original 1976 military decree that transferred all land in the new capital to the federal government. The plan was to evacuate the area, leaving it for administrative purposes only, with no Nigerian able to claim citizenship in this capital district.

This changed after a 1978 survey by Nigeria’s University of Ibadan showed that the local population, estimated initially by a government committee at 50,000, was closer to 150,000. The study found that evacuation and resettlementwould cost $17m—more than a third of Nigeria’s total $48.5m budget at the time,according to central bank figures.

This prompted the military ruler at the time, Olusegun Obasanjo, to discard the plan. Instead, he decided to prioritise spending on infrastructure in Abuja’s central 250 square kilometres—named the Federal Capital City (FCC). The new policy was to evacuate, resettleand compensate only the FCC’s indigenous residents.

The government offered to provide farmland, homes and compensation to citizens moved from the capital city. Gladys Luka was moved in 1990 from Abuja’s Maitama neighbourhood, which today hosts several foreign embassies. The 57-year-old cleaner now lives and works in Kubwa, a resettlement town 26km north of the capital. For the five plots of land she and her husband lost, the government gave her a small three-bedroom apartment. They also promised the couple farmland, but these fields never materialised, neither did compensation for their crops, she said. “I don’t expect they will ever pay,” she said. “What can we do?”

The government changed tack again in 1992 and switched from a resettlement policy to an integration plan that provided locals with basic amenities while they remained on their city land. After successive military governments failed to implement this programme, it was dumped in 1999.

A new FCT minister resumed the resettlement plan in 2003, but again achieved little—partly because of official corruption. A 2012 FCT investigation found that officials accepted bribes to transfer homes meant for Abuja locals to other Nigerians. The report did not disclose the names of the offending government staff. More than a year after it was submitted to President Goodluck Jonathan, no one has been punished.

“Everyone should by now agree the Abuja people have been badly treated,” said Ubong Ben of Abuja-based Facts and Figures, an anti-corruption outfit. “After taking over the lands without compensation for ages, violations like this present the government with an opportunity to demonstrate its concern.”

Yet the Abuja administration continues to appropriate farmland from Abuja’s original inhabitants,said Samuel Ogala, a property lawyer and activist who has tried to win compensation for his clients. The government pays for the value of the crops or trees grown on the property it appropriates. But if the land is fallow, the owners are not paid, losing potential earnings. This practice goes beyond eminent domain, the legal right of a government to take private property for public use, such as to build a road or bridge, because often the seized lands are transferred to private developers who build estates. The government claims that the Nigerian constitution and the Abuja Act give it ultimate power over all the capital’s lands.

But Abuja’s indigenes have fought back for years, citing another clause in the constitution: section 44, which stipulates that all properties seized should be paid for. “If you buy a commodity from the market, don’t you pay?” asked Shagari Sumner, OIDA secretary.

Mr Sumner also rejects the government’s position that the Abuja Act allows the state determine the compensation amount. He argues that the constitution allows a property owner to seek legal assistance to decide a favourable value for his or her property.

Mr Ogala, the property lawyer, estimates that 90% of Abuja’s original residents have not been resettled because the government has not respected its own laws.

While parties have differing interpretations of the constitution, the Abuja Act and the capital’s master plan, lawsuits proliferate and the controversy festers. After 38 years without either resettlement or compensation, residents say they prefer to remain on their land. “What we are even saying now is that they should allow us [to live] in our place,” said Akila Dikko, a middle-aged pastor who runs a small church in Kutako. “We don’t want resettlement. We want to build our homes.”