Africa’s Chinese-built super highway: cheap or a slippery road to surveillance?

Drawing the line between infrastructure and national security

by Richard Poplak

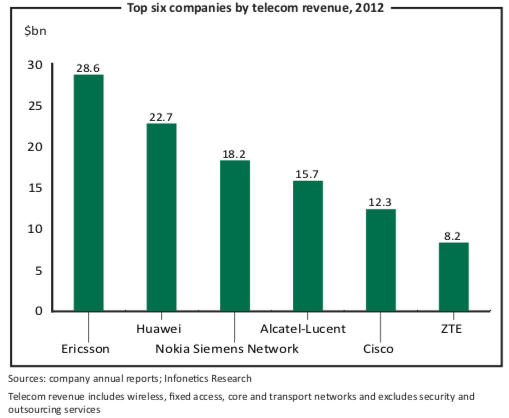

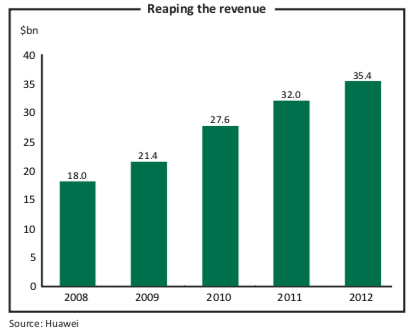

The Chinese company Technologies, the world’s second biggest telecommunications giant after Sweden’s Ericsson, does not attract much affection. It is subject to the usual opprobrium heaped on China’s monster corporations and riddled with so-called “reputational concerns”. Critics accuse Huawei of benefitting unfairly from cheap government money, stealing competitors’ intellectual property (IP) and being uncomfortably cosy with China’s military.

Following a series of investigations, American and Australian lawmakers have banned Huawei from bidding on massive telecoms infrastructure projects, fearing that this would be tantamount to giving Beijing a free all-you-can-listen service in Washington or Canberra. According to Michael Hayden, the former head of the US Central Intelligence Agency and the National Security Agency (NSA), there is hard evidence proving that Huawei has spied for the Chinese government in the past. Mr Hayden, now a director at Motorola, has not been forthcoming with said proof, but this has done little to dull the sting.

In this golden age of electronic espionage, African governments appear remarkably sanguine on the Huawei issue. The company won a contract in July to expand Ethiopia’s mobile phone infrastructure, providing 4G capabilities in Addis Ababa and 3G throughout the rest of the country. The contract represents a $700m addition to the more than $3.4 billion in revenue emanating from the company’s African operations, roughly 10% of its global total. Huawei first arrived in Egypt in 1999 and now boasts 5,800 employees in 18 offices across the continent. Yet in a recent Foreign Policy article, titled “Africa’s Big Brother Lives in Beijing”, Huawei is described as “basically an intelligence agency masquerading as a tech business”, one that is “wiring the continent for surveillance”.

Is Huawei Beijing’s eyes and ears in Africa? Or is it a benign company building the continent’s infrastructural future on the cheap? The Foreign Policy article is short on proof and long on accusations, yet its hypotheses are hardly surprising given the sensitivity of the work that Huawei performs. The company is an “end-to-end” supplier of information and communications technology (ICT) infrastructure, which means that it installs, operates and maintains the computerised controls that pull the puppet strings of the 21st century nation state. As the company’s chief executive, Ken Hu, has pointed out, “The internet will become another form of infrastructure, just as electricity and roads did in the past.”

Part of Huawei’s ineradicable perception problem stems from the biography of its founder. President and one-time CEO Ren Zhengfei, 66, joined the People’s Liberation Army in 1974, serving on the engineering corps from which he was promoted to technician, engineer and deputy director (which holds no military rank). A star performer, Mr Ren was invited to the National Congress of the Communist Party of China in 1982, the sanctum sanctorum of power.

Aside from this potted profile, what kind of fellow is Ren Zhengfei? No one outside of his circle knows. He does not speak to the press and he does not make public appearances.

While Mr Ren has undoubtedly attended his share of high level banquets, Huawei stresses its independent origins as a child of the late premier Deng Xiaoping’s opening of the Chinese economy in the 1980s. In an open letter published in 2011, Mr Hu described Huawei (which translates as both “China can” and “splendid act”) as “a privately-owned civil communications equipment provider” that has no relationship with weaponised ICT programmes in China or elsewhere.

The company’s founding mythology, much like any tech company’s, involves how little capital was invested at the outset: after leaving the Shenzhen South Sea Oil Corporation in 1983, Mr Ren started Huawei in 1987 with just $2,500. “It is a matter of fact that Mr Ren is just one of the many [company founders] around the world who have served in the military,” states Mr Hu’s letter. “And it is also a matter of fact that Huawei has only offered telecommunications equipment that is in line with civil standards. It is also factual to say that no one has ever offered any evidence that Huawei has been involved in any military technologies at any time.”

This reveals little in terms of how dangerous the company could prove to be to its

customers. Huawei does not simply provide ICT infrastructure, but technology designed to govern the smooth functioning of every piece of infrastructure that matters: power grids, financial and banking systems, water systems, aviation and other transportation systems, oil pipelines, and almost anything that depends on a digital nanny. In many respects, ICT is the Ur-infrastructure, which is why the Australian government forbade Huawei any involvement in its $34.5 billion national broadband network, an opportunity that dwarfs the Ethiopian contract by many orders of magnitude.

There can thus be no doubt that Huawei’s services, should they be contracted, are central to the national security of any nation, large or small, developed or developing. At heart, the company’s debatable trustworthiness lies in its unsubstantiated ties with the Chinese government.

Does Huawei share information with Beijing? Does it operate with Beijing’s interests in mind? Ultimately, in matters of national interest or in times of conflict, who is Mr Ren’s master? As a recent US House of Representatives Intelligence Committee’s investigation into Huawei notes, it whittles down to whether Huawei “is influenced by the state, or provides Chinese intelligence services access to telecommunication networks, [and whether] the opportunity exists for further economic and foreign espionage by a foreign nation-state already known to be a major perpetrator of cyber espionage”.

That is a bit rich coming from the United States, a country that has normalised electronic spying on foreign nationals and its own citizens alike though the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act, programmes like PRISM and institutions such as the NSA. But no shred of information Huawei has released to date does anything to clarify its money trail, which would presumably explain its corporate hierarchy.

Huawei claims that it is a privately held company owned by its employees. Like any commercial company, it is financed by its shareholders and through loans. In most cases, however, loans from Chinese banks are extended to Huawei’s customers, while the company benefitted from almost $90m in government financial support for research and development (R&D) in 2010 alone. Critics claim that Huawei does not conform to even the minimum corporate disclosure best practices imposed on tech corporations bidding on massive Western tech projects. They assert that if Huawei wants a fair playing field, Mr Ren and company need to list at least a portion of Huawei publicly.

Given the evidence, or lack thereof, one would expect African governments to exhibit at least some circumspection regarding Huawei’s involvement in the continent’s communications sector. Not so. At the Shanghai Expo in 2010, South Africa’s then home affairs minister, Nkosazana Dlamini-Zuma, stated: “Huawei Technology [sic] has established one of its few research and development facilities in South Africa through which South Africans are able to access employment opportunities in addition to benefitting from skills development programmes. Government welcomes the company’s in- vestment in South Africa including foreign direct investment [FDI] as well as the company’s contribution to the country’s human capital.”

In this conception, Huawei ticks several important development boxes: it provides communications infrastructure at competitive prices; it pumps FDI into the local economy; it offers “knowledge transfer” to African workers. The company has a sophisticated community development programme, and on its website reminds us that it is not only fully compliant with black economic empowerment legislation, but “supports South Africa’s talent plan” by funding the University of Zululand and offering scholarships for postgraduate students. It backs ICT labs across the continent, including at the University of Cape Coast in Ghana, Moi University, Kenya, and the University of Cape Town, South Africa. It has, along with Microsoft, developed the 4Afrika beginner smartphone, engineered specifically for the local market.

On May 25th 2012, Huawei opened its seventh training centre in Africa, its first in a sub-Saharan Francophone country—a six-floor facility located near the train station in Kinshasa, the capital of the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC). The building comes with all the trappings and will provide 40 students a month with expertise ranging from third generation mobile phone services to video conferencing to cloud computing, according to the press material.

The DRC’s president, Joseph Kabila, officiated at the centre’s opening, which gives some indication of how seriously African governments regard communications infrastructure. The Chinese ambassador to the DRC, Wang Wing Yu, and the DRC’s post, telephone and telecommunication minister, Tryphon Kin-Kiey Mulumba, were also there. “The training centre will re-establish the DRC to its original position as the centre of intelligence in the middle of Africa,” Mr Mulumba said, which frankly, is not saying much. Nonetheless, for outsiders observing the pageantry of the ribbon-cutting ceremony, this intimacy appears ominous: another example of the Chinese buying African hearts and minds with shiny buildings and establishing a major technological foothold in one of the continent’s regional fulcrums.

For all their ostensible outreach, community or otherwise, Huawei’s absurd secrecy goes some way to explaining its sometimes shady reputation. “Their executives have it in their contracts that they’re not allowed to speak to the press,” a Sino-African expert with knowledge of the company told Africa in Fact. “They’re a case of company culture reinforcing national culture.” Where a South African reporter might expect a tour, however cursory, of the R&D centre, or perhaps a functioning telephone number for a public relations representative, no such indulgences are forthcoming. Their secrecy is not a marketing ploy, but a deeply ingrained suspicion of the results of prolixity.

Which brings us, once again, to the essential question: how entwined is Huawei with Beijing? According to the US House of Representatives Intelligence Committee’s investigation, “it appears that under Chinese law, [fellow Chinese telecom giant] ZTE and Huawei would be obligated to cooperate with any request by the Chinese government to use their systems or access them for malicious purposes under the guise of state security.”

In addition, critics point out that even with the best intentions in the world, the companies are susceptible to infiltration from Beijing-directed moles or spies who could do more than practice mere espionage, corporate or otherwise. By inserting compromised hardware or software (malware) into a state’s infrastructure grid, Huawei could provide Beijing with the first line of cyber offence during times of conflict. In this, does China possess an asymmetrical weapon that instead of dispensing a mushroom cloud, sends a country into the stone age at the flick of a switch? Alternatively, China could “launder” cyber attacks on other nations through African servers rigged for just that purpose. (Or African governments could “request” the implementation of spy packages to keep an all-seeing eye on their citizens.)

Since the Edward Snowden whistle- blowing case blew earlier this year, we know that Google, Facebook and other large, publicly traded tech companies are compelled to cooperate with the US government’s big data spying programmes. The Guardian reported last June that South Africa was subject to a British wiretapping agency GCHQ (Britain’s signals-intelligence agency) hacking programme launched in 2005. In the spy vs spy nature of the wired world, there are no good guys. One thing is certain: regardless of who is implementing vast, vital ICT systems, African nations need a mitigation strategy.

Yet even in the West, institutions are often far behind the cyber warriors who are so successful at infiltrating them. The staggering amount of technology involved in building the firewalls that (sometimes) contain a nation’s ICT infrastructure does not appear to be taken seriously in many African capitals, where a minister’s business card might be embossed with a hackable Gmail or Hotmail e-mail account. And while no hard evidence of Huawei’s involvement in espionage or cyber warfare has ever been presented in a public forum, African countries should ensure that at least a part of their ICT implementation budget is ceded to independent auditors. Any disconnect between infrastructure and national security policy will ultimately leave a country both less developed and less secure.

In the UK, a recent parliamentary Intelligence and Security Committee report noted that the government was able to leverage Huawei’s “reputational concerns” into a UK-based, Huawei-operated cyber-security evaluation centre called “the Cell” (which still has not assuaged edgy parliamentarians’ fears). African states had best start doing some leveraging of their own: for while Huawei offers the future at a discount, it may still come at too high a price.