China’s loans to Angola: aid, investment or trade?

by Lucy Corkin

China is financing and building bridges, dams, highways, power plants and rail lines from southern Angola to Sudan in North Africa. It is one of the continent’s most significant yet controversial spenders on infrastructure.

Keen to get its hands on Africa’s mineral wealth, China, through its state-owned Export-Import Bank (Exim), has extended resource-backed credit lines to the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), Ghana, Zimbabwe and other countries. However, the details the bank uses to finance these projects are not well known. Many see these package deals as foreign aid handouts and a strategy to curry favour with African governments while elbowing out western donors.

But dig a little deeper and what emerges is that China Exim Bank is neither making grants nor providing aid. It is making loans like other commercial banks; what some mistake for aid, is actually trade financing on the continent.

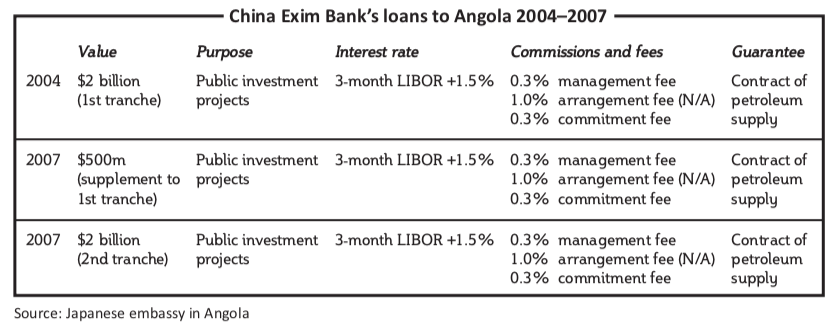

China first entered Angola as a financier in 2004, when Exim Bank signed an agreement extending $2 billion of credit lines to assist Angola in rebuilding its infrastructure, which had been devastated by 27 years of civil war.

Over the years, China has increased these credit lines to Angola several times and they reached about $10.5 billion between 2004 and 2010 with China Exim Bank alone. A key feature of these infrastructure loan projects is that they call for Chinese construction companies to be the main contractors.

In Angola’s case, the initial loan is repayable at the three-month London Interbank Offered Rate (LIBOR) plus 1.5% over 17 years, including a grace period of five years. This loan is cheaper than the oil-backed credit previous western financiers extended to the Angolan government.

Exim Bank structures its loans so that there is a revenue stream that supports the debt repayment. The agreement requires Angola to supply China with a fixed amount of oil on a quarterly basis, which is valued according to the international spot price on the day of shipment.

The price that China pays is determined by current international market prices. China Exim Bank loans thus have elements of market-related commercial loans. However, the China Exim Bank repayment terms are much more favourable to Angola than the oil-backed financing arrangements brokered by western institutions, which were often based on a fixed price per barrel at a significant discount to market prices.

These deals do not have as much of a grant element as public loans from Korea or India, where the interest rate is less formidable. Where China Exim Bank provides advantageous terms for Angola is in the length of the repayment terms: 17 years compared to four to five years demanded by European commercial banks.

A further bone of contention is how to label these loans. China Exim Bank’s credit lines do not fall neatly into the categories of trade, aid or investment. Instead, they display characteristics of all three.

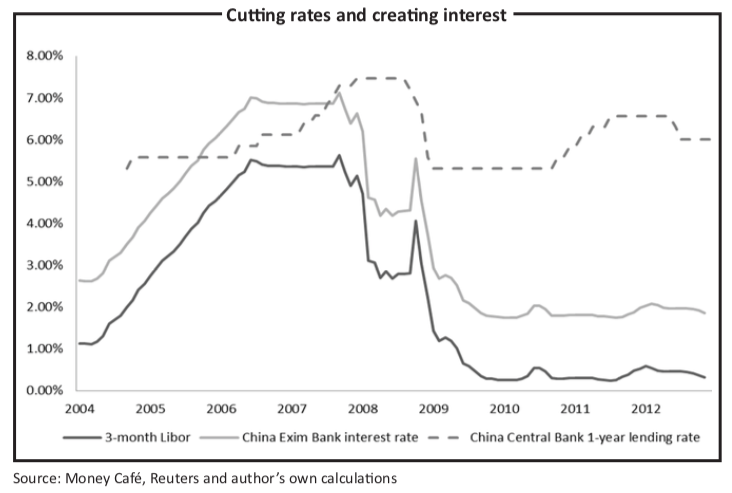

Several organisations, including the World Bank, have remarked on the “deeply concessional” nature or low interest rate of Exim Bank’s loans to Angola. Few of these loans fit the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development’s (OECD) definition of official development assistance: “flows of official financing to developing countries which have an economic development or anti-poverty purpose and are concessional [interest rate or grace periods more generous than market loans] in character with a grant element of at least 25% (using a fixed 10% rate of discount).”

Comparing the lending rate of China’s central bank with Exim Bank‘s loan to Angola provides the percentage of the loan that can be called aid. China’s foreign aid department, located within its Ministry of Commerce (MOFCOM), is required to subsidise the difference between these two lending rates. China Exim Bank’s floating interest rate renders an average grant component of 17% for the life of the loan, falling below the 25% grant element required by the OECD. Therefore this loan does not meet the OECD definition of foreign aid: it is not concessional because its grant portion is not high enough.

China Exim Bank’s credit lines initially helped to ease Chinese (mostly state-owned) companies’ investment in Angola’s construction sector. Although many Chinese companies entered the market with the help of China Exim Bank, they are now pursuing contracts independently of the state credit line, according to the Chinese ambassador in Luanda, Angola’s capital. Even contracts separate from the credit line do not necessarily entail direct investment. Actual recorded Chinese foreign direct investment was just under $350m in 2010, whereas Chinese construction companies signed contracts worth about $22 billion in 2009.

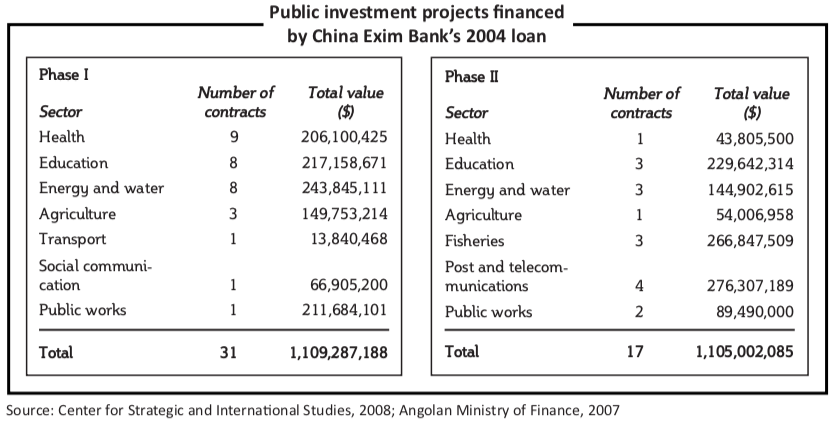

The loans themselves are not considered investment as they are structured so that the Angolan government repays them in full. The credit mechanism (on paper at least) converts Angola’s oil revenues directly into public infrastructure construction contracts with Chinese companies, and ties into Angola’s public investment programme.

Angola is currently China’s largest African trading partner, primarily due to China’s hunger for crude oil. According to the Angolan Ministry of Petroleum’s latest available statistics, 39% of the country’s crude exports went to China, accounting for 15.7% of China’s total oil imports. According to UN Comtrade (the world’s trade database), Angola is the fifth-largest African market for Chinese exports, but these are dwarfed by Chinese imports of crude oil, resulting in China running a large trade deficit with Angola.

The Chinese embassy in Angola has made it a priority to increase Chinese exports to balance these trade figures. As a result, the procurement policies linked to China Exim Bank’s loans take on the strategic purpose of reducing its trade deficit with Angola.

Exim Bank still funds most of the Chinese projects in Angola. Its loan conditions require that no less than 50% of the project procurement be sourced in China. Some space exists for African governments to negotiate the terms for hiring local labour, as in Angola. But Exim’s lending is still prescriptive as the bank’s primary function is to stimulate demand for Chinese goods and services.

In the end, these loans are neither aid, trade nor investment, but part of a larger package focused on export promotion. MOFCOM’s foreign aid department subsidises a portion of the loan, but not enough for the entire loan to be considered foreign aid. Nor can they be considered investment only. Rather, they are a way to secure oil and open up markets for Chinese (predominantly state-owned) companies’ goods and services.

Exim Bank finances the building of much-needed African infrastructure by Chinese companies, which, according to Angolan officials, would be cheaper than corresponding Brazilian or Portuguese tenders if there was open bidding. However, these transactions are open to corruption. The International Monetary Fund, the World Bank and others have criticised them for their lack of transparency. In the end, the success of China Exim Bank’s resource-backed deals rests on African governments’ skills at the negotiating table, their management of the loan implementation and their supervision of the infrastructure projects that the country’s natural resources have financed.