More than half the world’s population now lives in towns or cities, according to the United Nations Population Division. In Africa, less than 40% do. This proportion will increase as more people move to urban areas in search of better economic opportunities. Anton Ferreira discusses the effects of urbanisation and what can be done to make the process smoother.

Africa stands at a crucial juncture as its cities swell with a tide of humanity—a tide that promises vast opportunity, but threatens to become a tsunami of misery.

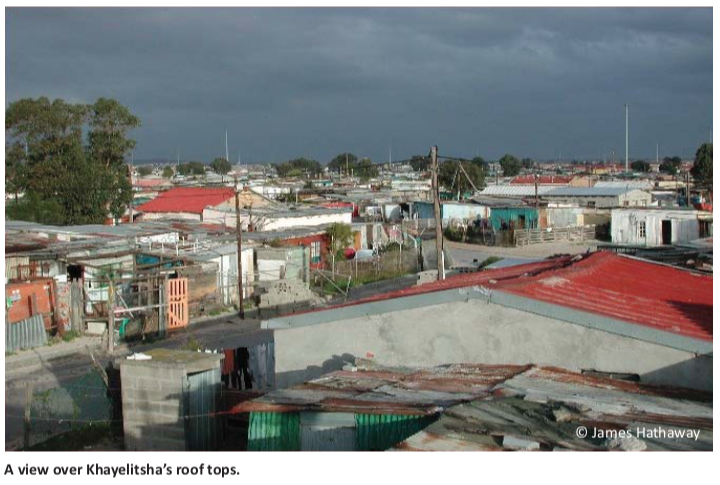

The sprawling slum of Khayelitsha outside Cape Town is a stark example of the desperate conditions in which the majority of the continent’s urban population lives. Despite being located in one of sub-Saharan Africa’s most successful economies, half of the slum’s 407,000 residents live in makeshift hovels built with cast-off sheets of corrugated iron.

Erected cheek-by-jowl in a low-lying area prone to flooding, these shacks offer little protection from the elements. The stink of raw sewage fills the air, gaunt dogs scarred by mange scavenge what they can and litter collects in wind-blown drifts along the muddy tracks that serve as streets.

Khayelitsha has become notorious for attacks by “vigilante” groups on people suspected of crimes. News reports tell of mobs killing young men accused of stealing items like cell phones. The police appear incapable of maintaining law and order.

Just 20km away in suburbs like Camps Bay and Clifton, international celebrities and jet-setters party in spectacular mansions in some of the world’s most sought-after real estate.

The striking contrast between rich and poor is a pattern repeated in cities across sub-Saharan Africa—islands of affluence surrounded by oceans of poverty.

As one measure of African deprivation, the United Nations Human Settlements Programme (UN-Habitat) says a study in 2008 showed that 22m urban Africans without toilet facilities routinely defecated in the open.

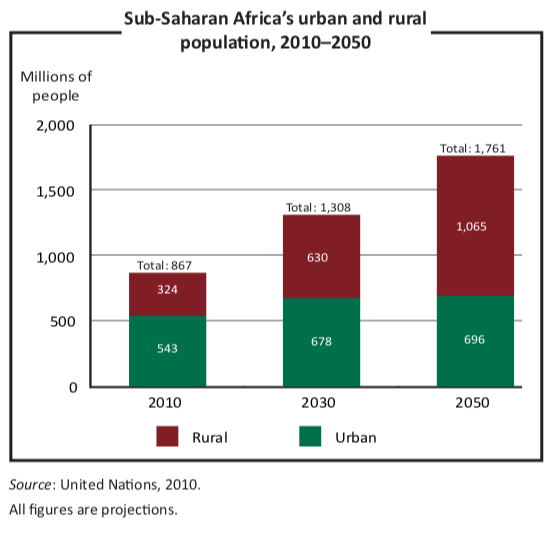

UN-Habitat, in its “The State of African Cities 2010” report, estimates that the continent’s current population of one billion will double by 2050 and that 60% of those people will live in cities, as opposed to 40% now. Lagos, Nigeria, will have overtaken Cairo, Egypt, as Africa’s biggest city by 2015 with an estimated 12.4m people—double its population of just 20 years ago. Kinshasa, Democratic Republic of the Congo, will be the second most populous city in sub-Saharan Africa in 2015 with 10.7m people. Luanda, Angola, and Khartoum, Sudan, will be vying for third place with about 6m people each.

While questions have been raised about the accuracy of the UN projections, there is widespread agreement that African governments need to focus far more attention than they do now on how to manage the teeming multitudes in their urban centres.

With improved infrastructure and effective governance this concentrated human capital could help lift countries out of poverty, but history shows a more likely scenario could be bigger slums and deeper chaos.

UN-Habitat says governments on the continent need to act quickly to be ready for predominantly urban populations.

“Since cities are the future habitat for the majority of Africans, now is the time for spending on basic infrastructure, social services, and affordable housing, in the process stimulating urban economies and generating much-needed jobs,” its report said.

Researchers warn that the attention national governments bestow on the problems of African cities is conspicuous by its absence.

In a publication from the African Centre for Cities (ACC) at the University of Cape Town, Professor Edgar Pieterse and his colleagues write: “We would strongly suggest that the dominant policy response to the deepening crisis associated with urban growth and expansion is inertia.”

Most political leaders refuse to accept that their societies are urbanising “at a rapid and irreversible pace”, Pieterse says. “This widespread denial, which is both tragic and dangerous, creates a public policy vacuum that leads to unregulated and unmanaged processes of surreptitious

urbanisation.”

Researchers believe that the essential first step is to reform property tenure systems in urban areas. One of the main causes of slum creation is that the poor live precarious existences in homes they do not own, on land over which they have no rights. They cannot afford to buy or rent property through formal channels, so they resort to squatting on whatever vacant land they can find on the peripheries of cities.

“The urban poor who live in informal settlements must be recognised and afforded security in our cities,” Pieterse says. “If the urban poor are protected from forced evictions and extortion they are more likely to prioritise the education of their children.”

He describes a “virtuous circle” in which residents of shack cities, assured of security of tenure, shift their focus from mere survival to growing small-scale enterprise and making a greater contribution to the urban economy. “This will generate demand for more services and finance which in turn has the potential to grow the tax base for infrastructure development,” he writes. “But this begins by fundamentally changing mindsets among political and administrative leaders—a task more difficult than it seems.”

Pieterse and his colleagues argue that it is essential to empower slum-dwellers and the rest of the urban poor if African cities are to be made to work.

“The most urgent priority is to create an incentive system for the urban poor to organise themselves effectively to advance their own interests,” they write. They envisage groups of slum residents pooling what little savings they might have—along with their knowledge, expertise and social connections—as a way of leveraging their resources on the principle that a community working with a common goal can achieve more than individuals could on their own.

The ACC researchers recommend that governments create unskilled jobs linked to infrastructure installation and maintenance, and to environmental activities like recycling and waste removal, and they say more attention must be paid to data collection and analysis.

The confusion over data is writ large in the debate over the very figures cited by the UN for the size of African cities and the pace at which they are growing. The UN largely bases its calculations on censuses conducted by national governments, but some researchers question how accurate such calculations can be.

Deborah Potts, a human geography researcher at King’s College in London, notes that census information in Africa is often problematic or contested, and the definition of what constitutes an “urban” area differs from country to country. “Demographic data do not corroborate the received wisdom about rapid urbanisation in sub-Saharan Africa. The evidence in many countries indicates an increase in the urbanisation level of only about 1% per decade,” she writes in the Africa Research Institute publication Counterpoints.

“The Democratic Republic of the Congo, said to have the third-largest population in sub-Saharan Africa, has not conducted a census since 1984,” Potts says. “This renders population figures and projections for Kinshasa little more than guesswork.”

In West Africa, the Africapolis demography project—affiliated with the French Development Agency (AFD)—uses satellite images combined with data gathered on the ground to estimate population sizes and comes up with very different figures to the UN’s.

A case in point is the capital of Burkina Faso, Ouagadougou. The UN calls this Africa’s fastest-growing city, saying its population was 1.9m in 2010 and will balloon by 80% to 3.4m by 2020. Africapolis, however, gives more modest figures of 1.4m and 1.8m respectively. Given that UN agencies say the city’s growth is fuelled by natural reproductive increase, rather than migration from other areas, the Africapolis figures appear on the face of it to be more reasonable.

Nevertheless, no one disputes that sub-Saharan Africa is becoming more urbanised, with much of the growth occurring in centres with populations below half a million people.

Also writing in the ACC publication, AbdouMaliq Simone says urban managers should take advantage of the very qualities that make African cities such vibrant centres of activity and commerce.

“Clearly, urban Africa’s historical strengths have centred on adaptability and resilience,” he says. “These strengths are not always, or even usually, efficient in conventional terms, and they counter assumptions that government must order, structure and control.”

With the IMF forecasting economic growth of more than 5% for most of sub- Saharan Africa this year, the continent is shrugging off its basket-case image, thanks at least in part to the commodities boom. But analysts say it could do much better if it fixed its cities.

Those who see the cup as half-full, rather than half-empty, include Monitor, the US-based corporate consultancy. “Cities today generate most of the sub-continent’s wealth, with many thriving despite obvious challenges,” it says in a 2009 report.

Cape Town, again, is a good example. Despite the benefit of a solid tax base in the relatively well-off suburbs, municipal authorities perennially complain that they cannot dramatically improve conditions in slums like Khayelitsha without more help from the National Treasury.

Ivan Turok, deputy executive director at South Africa’s Human Sciences Research Council, said in a recent article in South Africa’s Business Day newspaper that investment decisions in transport, electricity, water, sanitation and land use became more productive.

Countries that seemed to be getting it right included Botswana and Rwanda, Turok said in an interview with Good Governance Africa. “The fact [that] these are quite small countries, in which the cities are obviously very significant strategically, may help.”

Countries that were not getting it right were Zimbabwe and Angola, he added. “Both have been very tough on rural migrants settling in their cities. In both cases political power bases lie outside the cities.”

Pieterse agrees that some governments regard urbanisation as “something bad or undesirable. This attitude arises from the particular blend of national liberation ideologies that accompanied the post-colonial era.” These ideologies, he says, romanticised the notion of returning to the land. “Many governments and former liberation movement political parties hold a deep disdain for urban life and the ‘modern corruption’ and defilement of pure African identities found there.”

Anna Tibaijuka, a former executive director of UN-Habitat, believes one way to slow the expansion of slums in Africa’s major cities is to focus on developing smaller urban centres in rural areas, where people can find work in the processing of agricultural products, for example.

“If you look at Africa in the next 20 or 30 years, the jobs will come from the agricultural sector in value addition,” she said in an interview with the Financial Timeswebsite This is Africa. “This is why you need rural growth nodes, small urban centres, which then become a major source of employment so that people do not have to come into the slums.”

Potts says sub-Saharan Africa needs “massive investment in industries which collectively employ hundreds of thousands of low-skilled people”—like the textile factories of Asia—if it is to sustain economically favourable urbanisation.

The virtuous economic circle of urbanisation leading to increased productivity and greater consumer demand is not working as well in Africa as it is in Asia, she says.

“Economic liberalisation and attendant crises rendered sub-Saharan Africa unable to compete,” she says. “Global competition was forced upon towns and cities before most governments had moved beyond the earliest stages of establishing an industrial and manufacturing base.”